In my early teaching career, few pedagogical issues have caused me greater frustration than designing and enforcing late policies.

As a student, I had the luxury of not having to worry about this issue very much: Almost invariably, in the tug-of-war between perfectionism and procrastination, perfectionism won out at the eleventh hour. Once I had students of my own, though, I was shocked to see just how frequently kids blew past deadlines, or simply failed to submit any work at all.

(Just how common is this problem of late and non-submission? Checking my gradebook from fall 2019, my last non-Covid semester in the high school classroom, I found that for one major assignment, 8 out of 115 students, or ~7%, submitted late, and one did not submit at all. You probably won’t be surprised to hear these numbers skyrocketed during remote school—for one project, 17 out of 118 students, or ~15%, did not submit anything. If I had to guess the proportion of students in my classes who, for one major assignment or another, either missed a deadline or never turned in anything, I’d put that figure north of 25%, and possibly even at 35% or 40%. These rates are, to say the least, concerning.1)

Maybe I was unusually bad at getting kids to turn their work in, but from exchanges I remember with colleagues, I think my numbers were pretty representative. Given how often kids miss deadlines, then, a thoughtful educator needs to have a clear code in place for how to respond when they do. Of course, a teacher could just deal with every situation on a case-by-case basis, docking points as they deem appropriate, but this introduces its own host of problems—including, but not limited to:

Bias and Noise— A teacher who treats each late submission as its own unique case risks judgment tainted by mood, stereotyping, or if the student happens to unconsciously remind them of their buddy from college. This is fundamentally unfair.

Administrative burden — Even if it were possible for a teacher to eliminate bias and noise from their treatment of individual cases (spoiler: it’s not!), they would still need to somehow keep track of all those cases to ensure they were being consistent. This requires significant time and mental energy that could better be spent elsewhere.

Mixed messages — A lack of a clear and consistently enforced late policy undermines the importance of timely completion. At best, such laxness slightly devalues the efforts of the students who do meet the deadline. At worst, it creates a perverse incentive wherein students gain an advantage by tinkering with their work well past the point when it was supposed to be submitted.

When I say “late policy” of course I really mean late penalties—and I realize some might question whether punishing students is necessary in the first place. I’ll get to that. For now, suffice it to say that as long as such penalties do exist, there are better and worse ways to implement them.

From this perspective, I’d now like to share the evolution of my own late policy over the past few years—and its broader lessons for the rules we all make, break, and follow.

I. A New Teacher Gets Schooled

Before I entered the classroom, I naively assumed this was a clear-cut issue: If work is on time, it gets full credit; if it’s late, it’s marked down.

Once I started teaching, though, I quickly learned how this seemingly simple rule breaks down: A decision to penalize late work says nothing about how much to penalize late work; and “late” is a significantly fuzzier concept in practice than in theory.

On the first question—how much to actually deduct for late work—I had an easy answer: I was covering for a colleague on maternity leave, so I simply adopted her existing policy for the one semester I was teaching her class. In this case, the existing policy was that essays and projects were marked down half a letter grade for each day they were late.

On paper, this penalty sounded reasonable enough, but I failed to anticipate just how quickly the deductions would add up. Enforced as written, an A+ paper turned in a week late would be marked down to a C, and a B+ paper to a D. Past ten days late, even a flawless essay was guaranteed to earn an F. I was reluctant to change the policy midway through the semester (especially since it would only resume in the spring upon my colleague’s return); but I ended the fall thinking this penalty was too harsh. I don’t think a week and a half should spell the difference between passing an assignment and failing it.

On the second question—how “late” is defined—it’s easy to imagine a draconian cutoff; but in the real world, students have legitimate absences, emergencies, and technology failures, and a failure to respond to those situations can be insensitive or outright cruel.

Unfortunately, once the possibility is open for some exceptions, the teacher is in the position of having to adjudicate whose excuses are legitimate and whose are bullshit. This was exactly the kind of time suck and subjectivity I was trying to avoid in the first place!

I remember, for example, one student my first semester in the classroom who “forgot” to turn in an essay but swore she’d completed it on time. She showed me text messages from her brother corroborating her story; I remained unmoved; she cried.

I suspect this student was being less than honest, but I don’t know that for sure. And there were other similar situations where I opted for leniency (e.g., a student genuinely forgot to submit and could show me edit history clearly indicating timely completion). Because the late deductions accrued so quickly, these binary judgments—late vs. time—could have significant grade implications for students. And while I was never operating with perfect knowledge of who was telling the truth about the challenges they faced, my late policy discriminated sharply between the two categories, as if I had perfect certainty. I found this authority stressful and emotionally draining.

What I needed, I realized, was a return to first principles: Why did I have a late policy in the first place? What was the behavior I was hoping to instill in students—and what actually worked?

II. A Better Policy Is Born

The five rules in this section are the least bad late policy I’ve been able to come up with in my time in the classroom. For ease of comprehension, I’m going to present them in a fairly linear fashion; in reality, I arrived at them through extensive trial and error, tweaking the policy nearly every semester I taught—and suspect I’ll continue to do so in the future.

My first, and most important, realization was a personal admission about why timeliness mattered: At its core, the late policy wasn’t for students; it was for me.

Yes, meeting deadlines is an important life skill, and the reality is that many of us need the push they give in order to get our work done—but these student benefits were largely incidental. The truth is, in the day-to-day flow of school, my job was just made way shittier when students didn’t turn in their work on time. Instead of lesson-planning and providing meaningful feedback, I was wasting precious hours tracking down missing assignments, tallying late deductions, and worrying that their dog really had eaten their essay this time. With over a hundred students, this time added up, and I wanted my life to be simpler.

Once I got clear about my motivations and translated them into language students could understand, a lot of the annoying judgment calls and grade calculations disappeared overnight. This is the rule I now use, and the single strongest recommendation I can make for any educator instituting a late policy:

1. Work is “late” if I don’t have it at the time I start grading.

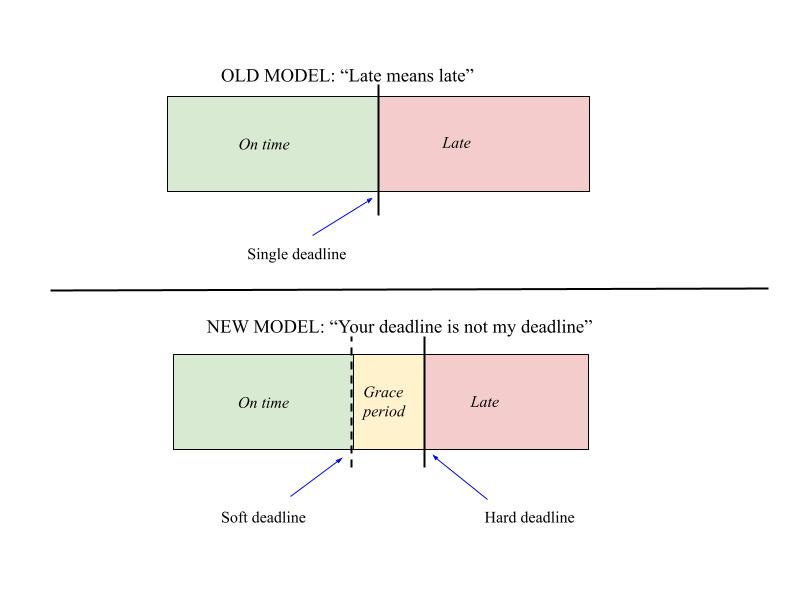

The simple but crucial innovation here is the gap between when something is due—i.e., the date that appears on the assignment instructions—and the date when it will be marked late. (Here, I’ll refer to these as the “soft deadline” and “hard deadline” respectively—though I mostly avoided this language when speaking to students, for fear of confusing them.)

The new model has profound advantages over the old model. While I’d worried that the grace period might create moral hazard wherein students simply adjusted to the “real” deadline, I found that this was rarely if ever the case. After all, the “soft deadline” is the only one that is transparent to students, so it tends to be the date that sticks in their heads. (In truth, even I often don’t know when the hard deadline is, because it’s subject to the whims of my own schedule and motivation.)

Additionally, students assume a legitimate—albeit minor—risk if they wait until the grace period to submit: Any issues encountered at that point are completely on them to solve. If they have a question about the assignment, that is, or their internet goes out, they can’t claim this as a legitimate excuse; technically, the essay was already supposed to have been submitted.

Fortunately, most minor, commonplace issues can be addressed during the grace period—so if, for example, a student’s computer really does crash at the last minute, it’s not a disaster; they have time to sort it out or make a plan with me. If, on the other hand, their computer crashes at the last minute and they somehow never got it working again—and they never figured out how to get in touch during the week before I started grading—well, either they’re a liar or an idiot; I feel justified deducting points in either scenario. Simply put, the grace period creates an intentional gray area outside of which answers are much more black and white.2

My second realization was that late penalties did not have to be very severe to serve their intended purpose. Out of this principle grew a standard penalty, which I thought of as the minimum viable deduction that wouldn’t create annoying math for me:

2. Late work will be marked down 5% for each week it’s late.

For me, this penalty was easier to calculate than a half-letter-grade-per-day deduction, and for late submitters, it had less of a negative impact. Plus, because -5% per week is a “slower-acting” penalty, its efficacy as an incentive lasts longer. This is because as soon as a student’s grade on an assignment drops to an F, they’ll likely feel they have little reason to push to get it done.

(An illustrative example: On the merits of quality, your work would earn an A. Mr. Harsh, your history teacher, deducts a full letter grade for each day an assignment is late, while Ms. Mellow, your math teacher, deducts a half letter grade every other day. Here, in Mr. Harsh’s class, you’re already in F territory after just four days; in Ms. Mellow’s class, on the other hand, you get a B+ if you’re four days late, a C- if you’re two weeks late, etc. Even after you’ve missed the deadline, you have incentive for up to several weeks afterwards to submit as quickly as possible.)

Granted, in practice, most late submitters probably aren’t giving a ton of thought to incentives; they’re just disorganized or demotivated. But I’d like to think it helps some on the margins, both psychologically and with their GPA.

My third realization was that frequently in the real world, deadlines are more negotiable than teachers like to pretend; a lot of times, a quick text or an email does the trick. (“Hey, turns out I’m pretty swamped this week—okay if we push the presentation to Monday?”) Not every deadline is like this, of course, but it felt like students were often being held to a higher standard than many adults are. While I didn’t want students to miss deadlines, I recognized that many would—and I wanted them to develop good instincts for what to do when it happened. I decided to give them some encouragement, in the form of rule #3:

3. The earlier and better a student communicates, the more lenient the late penalty.

In other words, while the “standard deduction” was -5%/week, I’d usually just take off 1-3 points if a student communicated beforehand, or even if they submitted late but let me know they’d done so. And if they asked for an extension proactively (like, multiple days in advance), I’d grant it no questions asked. But if they simply turned in an assignment without saying anything, or if I had to put a zero in the gradebook or track them down to get it, then I’d assess the -5%/week penalty exactly as written. This rule made my life a little more complicated, but it was a price I was willing to pay to try and save myself more annoying conversations later, and promote good student habits.

Finally, realizing that my first three rules didn’t quite cover everything, I added a couple more to deal with particular situations—first, a floor on the penalty:

4. Late work will receive a minimum of 50%.

(This I included simply because I didn’t want late work to completely tank students’ final grades. Although schools theoretically grade on a scale from 0-100, we actually use only roughly the top third of this scale; for this reason, a single grade in the 0-50 range can disproportionately drag down a student’s mathematical average to an F. A floor of 50% ensured that students weren’t irreparably setting themselves back, so long as they eventually turned in something for all major assignments.)

And last but not least:

5. Homework and live presentations cannot receive late credit.

(This caveat arose because homework and live presentations are, generally speaking, tied to a specific class period on a specific day. In other words, there’s little pedagogical value in preparing talking points for a class discussion after the discussion has already happened. If a student had a valid reason to miss class or some emergency prevented them from doing their homework, I might waive an assignment altogether—but I wouldn’t ask them to make it up solely for the sake of earning points.)

III. The Crank Comes Out

I think the time has come to address an obvious criticism: Why devote so much energy—and a 3,500-word blog post—to a complex ladder of discipline when it would have been easy to just accept all work for full credit, so long as I received something before the end of the semester? Why impose penalties at all?

If I’d been teaching, say, a single seminar of ten undergrads, I might well have opted to work individually with whatever stragglers there were to figure out a plan for submission. This is a more humanizing approach—and probably a more effective one.

But in a big public high school, there are certain realities to deal with. Asking teachers to expend a lot of effort tracking down missing assignments and negotiating deadlines with individual students is, frankly, just a bad use of school resources. Unfortunately, a teaching load of 100+ kids means that blunter instruments are both appropriate and necessary. (This isn’t to say I didn’t also talk in class about study skills, organization, and concrete strategies for getting work done—just that they weren’t the sole accountability mechanism I was relying on.)

Remember, too, that by the time they reach ninth grade, kids are coming in with a lot of attitudes about school that are beyond any one teacher’s control. A large portion of them don’t want to be there—have been trained to view assignments as a transaction: cognitive labor for grades. Much like the good little capitalists they will one day become, they have learned to be compliant and productive only so long as it’s in their own interests to do so. While I wish this weren’t the case—and have argued for more engaging curricula and less shitty grading paradigms in the past—for a lot of kids, it just is. Absent superhuman persuasiveness, then, teachers have just two big levers at their disposal for getting students to do things they’re not intrinsically inclined to do: the carrot or the stick. In the case of deadlines, the stick works best.

Plus, fine, I’ll admit it: I do think high schoolers should face consequences for not turning in their work on time—especially when they don’t take responsibility for the mistake. Not severe consequences obviously, but enough to sting a bit. Enough to convey: Dude, you’re sixteen. Figure it out. Naturally, some students—more often boys than girls—will struggle to meet this expectation, but that doesn’t mean the expectation should be abandoned. Just because a lesson doesn’t immediately translate into improved behavior doesn’t mean it hasn’t been received; some lessons simply take time to incubate.

IV. Grownups Have Deadlines, Too

Deadlines are a fact of life, and watching students struggle to meet them has been an invaluable mirror for how I think about my own work—and about policies in general.

The distinction between soft and hard deadlines, for example, crops up constantly. Just as I necessarily can’t do my job (grade) before students have done theirs (submit their essays), you cannot realistically plan your wedding without the RSVPs, or incorporate a friend’s notes on your cover letter mere minutes before the application is due. Most collaborations are like this: not a pass you catch in the endzone, but a handoff that still needs to be run in for a touchdown. So the honest answer to “When do you need this by?” is often significantly earlier than the date you’re hoping to finish it by.

Even in the absence of a naturally occurring soft deadline, we can often create them for ourselves. A train departure time is converted to a must-leave-the-house-by time. A project launch date is converted into a more conservative project completion date. While these kinds of mental gymnastics don’t always work perfectly, they increase the likelihood that we’ll stick the landing.

With respect to policy design in general, my biggest takeaway has probably been the importance of good defaults. While I had devoted a lot of thought to my five rules, it was abundantly clear that most students had not given them a very close read. Fortunately, I’d designed my late policy in such a way that the less-than-perfectly-informed weren’t screwed.

For example, I sometimes got emails from anxious students who had missed a due date by a couple minutes, in spite of my assurances that they had an automatic grace period—no harm, no foul! And no matter how much I stressed and incentivized communication, many students continued to quietly upload late work without any acknowledgment that it had been missing for weeks. In this case, I assessed the standard penalty (-5%/week)—but they faced no extra deductions for their reticence.

In fact, while it had been important (both for the sake of equity and my own sanity) for me to think through the policy in great detail, for students it could be boiled down to two simple principles: 1. If something is only a little late, it’s fine; and 2. The earlier you communicate, the better. If they wanted to get into the weeds, everything was technically there for them on the syllabus; but if they only followed the spirit of those broad-strokes ideas, they’d very likely be golden.

Finally, one idea I think is generalizable, but have less confidence in: bounded discretion. That is, we want to believe rewards and punishments are responsive to the unique circumstances of the individual, and an overly mechanistic policy can feel inhumane. At the same time, all the evidence suggests that subjective human judgments quickly lead to unequal outcomes. In this vein, one aspect of my late policy that I came to be very grateful for is that I’d given myself a few small levers to pull—i.e., depending on when/how a student communicated—but these decisions were secondary to the broader framework of the grace period and the standard penalty. Sometimes I almost felt as if the policy itself was playing bad cop and I, its human enforcer, was playing good cop within certain predefined buckets—although of course I was ultimately responsible for both.

I’m not sure if this case study will be interesting to those outside of education—or even to those within it. What I do know is that everywhere I look, there are people wrestling with the thorny question of how to create rules that are both fair and kind. My experience in the classroom has taught me that it’s impossible to anticipate every challenge that will arise in this situation; you just come up with the best policy you can and, when it doesn’t work, try to make a better one.

As I’ve written in the past, this discrepancy (between timely submitters and partial or non-submitters) led to the biggest academic gaps in my high school classes—far bigger than any that resulted from seeming differences in ability.

Interestingly, after adopting my new late policy, I was surprised to learn in discussions with colleagues that many of them were quietly practicing their own version of soft and hard deadlines, and were often cutting students more slack than their syllabi suggested. This is good in the sense that it leads to better grade outcomes, but it obviously favors those who are willing to work the system to their advantage. Personally, I feel much more comfortable making the codes of acceptable behavior explicit to students, even if they don’t all end up following them. Plus the grace period is a zero-cost opportunity for teachers to earn trust from the class: a win-win!