Cross-grading

A more humane approach to academic assessment

In the Real World™, your coach doesn’t referee the game.

In other words, the person responsible for overseeing and improving a person’s skill or work generally isn’t the one who ultimately evaluates how good it is. While the consumer (client, audience, etc.) cares almost exclusively about the finished product, your manager or editor must know how to motivate you, give you feedback, and get you to actually make the thing. (Of course, your supervisor’s opinion may well be a strong predictor of how your work is received, not to mention your likelihood of promotion.)1

Despite this, it’s taken for granted for the first 2+ decades of our lives that our teachers will serve as both our guides in the quest for knowledge and the ultimate arbiters of whether we’ve succeeded in that quest: They teach us geometry—then they give us a geometry test. They teach us how to write an essay—then they give us feedback on that essay. They teach us how to shoot a free throw—then they give us detention when we repeatedly throw the basketballs at high velocity at each other’s genitals.

The reason for this grading model seems obvious: It’s theoretically easier and cheaper to hire one person who can both instruct and evaluate at the same time. But this system creates certain problems that, having experienced them both sides, I believe are fairly pervasive in secondary and higher education:

From the student perspective…No matter how genuinely interested you are in the subject matter, you can’t help but feel the inherently transactional nature of the grades-for-work paradigm. This makes it scarier to take academic risks, and more awkward to ask for help. (Will my teacher think I’m just coming to office hours because it will improve my grade? AM I just going to office hours because it will improve my grade?)

From the teacher perspective…No matter how genuinely invested you are in your students’ learning, there are limits to how much help you can offer any individual student without conferring an unfair advantage on them. Taken to an extreme: If I, as your teacher, go through your essay draft sentence by sentence and tell you exactly what would make it into an A paper, and then you just do what I tell you…is that really a sign of writing mastery, or are you just good at following instructions? (In this vein, a former colleague of mine used to tell students she could answer specific questions about an essay draft, but couldn’t “pre-grade” it, which I think is a nice framing.)

In this post, I’d like to explore a potential alternative grading model, which I believe could help reduce strain on the student-teacher relationship: splitting the responsibility for instruction and evaluation between two or more teachers. For the time being, I’ll refer to this idea as “cross-grading.” (I suspect different terms exist for similar concepts that I’m just not aware of, and am happy to adopt them if I learn what they are!)

A Hypothetical

Let’s start with a hypothetical to try and imagine how this might work.

Suppose we have two English teachers, Ms. Gilda and Mx. Schmeckler, who agree to grade papers for each other’s classes: They will each simply accept the other’s subjective assessment and use that number in their respective gradebooks.

As the students begin the writing process, everything is more-or-less the same as it typically would be: Maybe both teachers give their students feedback on outlines or first drafts, maybe they just talk about what makes for effective writing. Perhaps some students hang back after class or set up a time to meet with their teacher to ask specific questions.

As students begin to receive and incorporate this formative feedback, however, the writing process begins to look a little different. Ordinarily, when a student gets input on a non-final draft of something, it’s almost guaranteed that they do better on it than they would otherwise: Unless the student completely misunderstands the teacher’s suggestions, or the teacher is a capricious asshole, all the student has to do is just fix whatever they’re told to fix.

(Every once in a while, a student would come to my office hours and I’d suggest, for example, that a certain piece of evidence they had wasn’t very strong—only to have them turn in the final paper with the exact same piece of evidence. This always kind of blew my mind. Even if they’d found an equally bad piece of evidence to replace it—even if they’d found a worse piece of evidence—at least I would have seen that they were trying! Ignoring the evaluator’s feedback is so much worse than never seeking help in the first place.)

In contrast, the cross-grading paradigm gives the student the ability to exercise discretion in implementing feedback, which both feels better and is much better preparation for a world in which (surprise) the exact same work can get radically different receptions from different people. Ms. Gilda can say, “You know, Johnny, Mx. Schmeckler really cares a lot about evidence—and I don’t think your evidence here is very strong,” and Johnny can respectfully disagree and decide to let Mx. Schmeckler make an independent assessment.

Importantly, when the students get their essays back, graded by an external teacher, they know the grade is not personal: The evaluator isn’t rewarding/punishing students for effort, class participation, and other factors extrinsic the writing itself. (Obviously as a teacher, I was never trying to reward/punish students for these things, but that doesn’t mean students didn’t think I was—and that perception of bias can, I believe, be really corrosive to the learning environment.)

Afterwards, if a student gets a grade they’re not happy about, their primary instructor can then help them strategize for the next essay and work through that frustration; this is self-evidently much easier to do when that teacher isn’t also a main source of the frustration.

Challenges

There are a few challenges to cross-grading that come to mind, both logistical and philosophical.

First, you obviously need sufficient cooperation and coordination for two (or more) teachers to grade each other’s assignments and accept the other’s evaluations. This very likely requires that they are covering the same material at the same time, which at the college level, is not the norm—and frankly, probably isn’t happening at a lot of high schools either. (At least it wasn’t at the one where I taught.)

Still, in a typical secondary school, this kind of partnership doesn’t seem like too tall a task, and it wouldn’t require too much extra work to pull off. In the simplest version, the teachers just agree on a shared assignment and due date, and then physically or electronically exchange students’ submissions after they’ve been turned in. I guess they technically don’t even have to have the same assignment and due date; that just feels cleaner and more sensible to me.

Second, it’s worth asking whether perhaps teachers should take individual factors and context into account when grading summative assessments—information about the student that can only be understood by interacting with them on a regular basis, like how much they’ve improved, or whether there are any extenuating circumstances that might justify a higher or lower grade.

My personal stance is that the more room for subjectivity there is in the grading process, the more stressful it is for all parties. Still, exceptions and accommodations are absolutely warranted at times, and I think cross-grading offers a potentially more equitable way to implement them: Instead of relying on students to advocate for themselves in these situations, the student’s primary instructor could identify any factors they believe should be taken into account by the evaluator. (E.g., They could make a note at the top of that student’s essay that the writer was out sick for much of the unit.)

Third, while I’m taking it on faith that cross-grading is a smarter, more authentic way to measure performance, it’s fair to ask whether students would in fact like it more. Isn’t there something nice about the clarity of I do what my teacher says → I get a better grade? Is it actually desirable to make school more like the “real world”?

Admittedly, I’m not sure of the answer to these questions. Probably, an individual’s attitude toward cross-grading will depend a lot on their own current relationship with their teachers and their grades: If you’re doing well under the current system, you probably don’t see much reason to change it; if you’re struggling, getting a second opinion might sound kind of nice.

That said, I think cross-grading offers little downside for high-performing students—who are, by and large, going to do well under any assessment system—and significant upside for low-performing students, who are presumably more likely to experience conflict and resentment toward the person making negative evaluations of them.

Other Possibilities and Considerations

In trying to envision how you could actually roll this out, I think there’s a few different ways cross-grading might be attempted.

Again, in its most basic version, two teachers would simply agree on some basic assignment parameters and coordinate a swap—but you could also imagine a more formal or centralized system for doing this (e.g., via an administrator or submission platform).

If two teachers wanted to work more closely together, you could have a more explicit co-teaching model, wherein students spend half the semester with one instructor, while the other teacher grades their summative assessments (and vice versa). This seems like a more practical way to run things at the college level, since each professor could more-or-less teach their own thing for their half of the course, so long as they felt comfortable with their co-teacher grading the assessments from that half. (I guess you also get an instructor-evaluator division of responsibilities when you have grad students do the grading?)

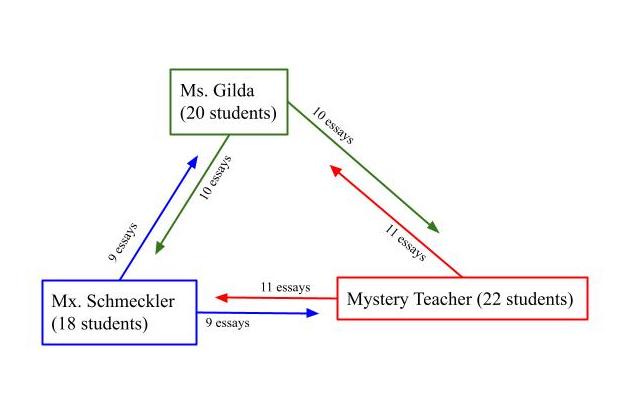

More complicated—but potentially more fair and fun—would be to set up a grading triangle: Ms. Gilda and Mx. Schmeckler send half their class’s paper to each other for grading, and half to a third evaluator. (Presumably this would happen multiple times so that students got feedback from both other teachers.)

I say this triangle arrangement is more fair because multiple graders make it more likely that idiosyncratic, subjective assessments will balance out. I think it could also be more fun because it introduces a possibility of competition: If the third evaluator does not know which papers are from which class (ideally they’re anonymized/randomized), then Ms. Gilda and Mx. Schmeckler can make a game of seeing whose students are stronger writers in Mystery Teacher’s eyes. The classes can even be in on it.

Consider, too, that cross-grading doesn’t have to be all or nothing: A pair or trio of teachers could opt to do it just for certain assignments, such as a final project. (In fact, there’s already a common version of this: the thesis defense. Or a non-college example: At the high school where I taught, juniors had to present their end-of-year English essays to a teacher other than their own.) So there’s already a recognition, I think, that cross-grading is a good idea when the assignment really counts; I'm advocating for an expansion of that system obviously, but how far that expansion goes will depend upon the individual school and teachers.

What would all this look like from the perspective of the instructors? On the one hand, there is admittedly something weird and sad about the idea that a teacher might not get to see the finished work of their own students. But I’d like to think that most teachers would end up relying more heavily on formative assessments (e.g., drafts and outlines), which they should probably be doing anyway. They might also go over the evaluator’s comments together with the student once the assignment had been returned.

As for the experience of grading the work of other teachers’ students (i.e., kids you don’t know), I think it would probably make most educators feel somewhat detached during the evaluation process—which, on net, I believe would be beneficial. As I’ve discussed at length in the past, grading is always going to be a bit tedious when you’ve got hundreds of assignments to get through. (Although again, in the triangle arrangement, you could perhaps make it more interesting by trying to guess which essays came from which of your colleagues’ classes?) The monotony of grading, however, is not the thing I always found most unpleasant about it…

In fact, the most agonizing part of evaluating student work, in this writer’s humble opinion, is that kids come into your class with such disparate experiences and abilities. With this heterogeneity comes the feeling that your grades are simply reinforcing inequality, rather than recognizing effort and ability. (The students’ effort and ability, that is. I certainly suspected at times that I was rewarding tutors’ and parents’...)

Maybe that guilty feeling doesn’t entirely go away if I’m grading essays from another teacher’s class—but at least cross-grading saves me from having to look a dyslexic student in the eye as, yet again, I hand them back a rubric with the spelling and mechanics section marked “needs improvement”; in the long-run, it’s no kindness to give students a false sense of their own abilities, but this system—our current system—just feels like such a cruel way for them to get the feedback.

(Again, the counterpoint to this kind of example is to make individual accommodations and modifications in the assessment process—which is, in many situations, more equitable, and is something I often ended up doing. In practice, however, it can be very difficult to differentiate for every individual need, and gets you into all kinds of slippery slopes as a teacher.)

Ultimately, I’m not suggesting that cross-grading is a silver bullet that will eliminate all the stress that comes with evaluating and being evaluated. I’m just saying that as long as grades are sticking around, we might as well be honest about what’s happening here, and attempt to better align student and teacher incentives.

TL;DR

A lot of awkwardness, conflict, and resentment in academic contexts stems from educators serving as both instructors and evaluators—a dual role rarely seen in other segments of society. I propose “cross-grading” as a solution: dividing these responsibilities between two or more teachers.

A possible exception to the editor/evaluator division: stand-up comedy? Here, (lack of) laughter = feedback for refining a bit and a kind of ultimate assessment of the work’s merits. This is unusual because a set, while perhaps “practice” for a special, is still a performance in its own right.

I give you an A+. Happy to discuss during my office hours. 😜