When Robots Outwrite Humans, Maybe English Class Will Suck Less

Rethinking curriculum in the age of generative AI

There’s a tsunami headed for the secondary English classroom, one that could destroy writing instruction as we know it—and could, just maybe, be totally tubular 🏄🏼🤙🏻.

I'm talking of course about the Large Language Model (LLM) called Generative Pre-trained Transformer-3—better known by its initials GPT-3, and recently integrated into a chat interface called ChatGPT. (You can try it for yourself here.) If you've missed the flurry of thinkpieces and news stories about this technology, these are a few of my favorite recent examples…

Exhibit A:

Exhibit B: “A robot wrote this entire article. Are you scared yet human?”

(To be clear, the article is actually an edited composite of texts produced by the computer, as noted at the bottom: “Editing GPT-3’s op-ed was no different to editing a human op-ed. We cut lines and paragraphs, and rearranged the order of them in some places. Overall, it took less time to edit than many human op-eds.” I’ll let you decide the extent to which the piece is worthy of its title.)

Exhibit C:

(These clips, from OnceUponABot, were generated in seconds using a short phrase as a prompt. They rely on images and audio narration produced by models trained in the same way that GPT-3 is.)

There are a lot of takes flying around about what GPT-3 can and can’t do now, and what it will be able to do in the future; I’m not necessarily qualified to make predictions on that front. (Even the people who are qualified differ starkly in their predictions about when we’ll have human-level artificial intelligence.) What I am qualified to do is teach English, and on that front, I have quite a bit to say.

A brief note on my approach:

I’m starting with the assumption that GPT-3 is already useful—and will soon be ubiquitous—in secondary English classrooms across the country. Given this assumption, my goals are to A) better define what “outwrite humans” means and B) lay out three broad patterns of response.

In answering these questions, I’ve found it useful to explore the tools from the inside out. I’ve opted not to include these experiments in the main part of this post, but am linking them here (and again at the bottom) for those who are interested:

Defining the Problem

Playing around with GPT-3 left me more than convinced that robots can indeed “outwrite humans” in meaningful ways—but this claim needs to be specified.

First, there’s the ambiguity of what “outwrite” means. In one light—which is to say quantitatively—GPT-3 can already outwrite all humans: That is, the sheer speed of its text output far exceeds that of mere mortals. Even if this text is not very good, the availability of cheap, abundant prose seems certain to disrupt society. (Some of these disruptions will be good, of course—like making it easier for non-native English speakers to communicate.)

Then there’s the question of whether GPT-3 is outwriting humans in terms of quality—and which humans it’s outwriting; here, the claim gets murkier. Right now, GPT-3 is clearly a better writer than most first graders and a worse one than most professional authors. But for the massive population between that lower and upper bound (most notably here, high school students) it’s better at some things and worse at others.

GPT-3 mostly avoids typos and sloppy grammar, for example—and there are certainly many people who will benefit from that. But as impressive as it is at form, GPT-3 consistently struggles with content. It’s fundamentally a bullshitter. (To the point of producing fake Catcher in the Rye quotes when I asked it to write an essay; see Appendix A.) All of this begs the question: How good does a student’s own bullshit detector need to be in order for them to bullshit effectively with GPT-3?

Put another way, I’m sure that using GPT-3, I could write a decent essay with far greater ease and efficiency than I could without; I suspect, though, that this is due in part to being well-acquainted with the book and having been made to write many five-paragraph essays of my own: I know what the product is supposed to look like.

I don’t mean to suggest that the five-paragraph essay is a particularly difficult or worthwhile form to master. (More on that later.) Clearly, though, there’s a minimum amount of knowledge required to know whether you’re producing a convincing fake—and that minimum gets higher the more substantial a writing task is. Maybe AIs will soon get good enough to produce high school essays with no assistance whatsoever, even for students without any independent capacity to evaluate the quality of the work. But you’ve got to wonder how far this goes—whether it scales up when the standards get higher and assignments get longer.

Finally, there’s another line of attack against GPT-3 I’d like to touch on—namely, that its prose is boring, and that this boringness is an inevitable function of the way it’s trained. Here’s

on this point in a recent piece about AI writing:AIs like ChatGPT are programmed to spit back the most expected material possible. They’re a long-form version of the email autoresponse features that pop up “Sounds good” and “Great, thanks” buttons.

Or as Eric Hoel puts it:

I think the banal nature of these AIs may be unavoidable, and their love of cliches and semantic vacuities a hidden consequence of their design. Large Language Models are trained based on predicting the next word given the previous ones, and this focus on predictability leaves an inevitable residue, even in the earlier models. But it especially seems true of these next-gen models that have learned from human interaction, like ChatGPT. The average response that humans want turns out to be, well, average.

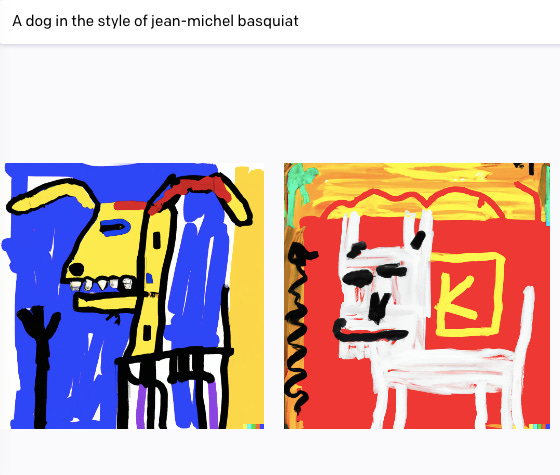

I was a little skeptical of these claims—or at least skeptical of the certainty with which the writers state them, so I spent some time playing around in ChatGPT with imitations of Ernest Hemingway and Toni Morrison. (See Appendix B.) My larger point is that even if GPT-3 can only produce derivative, formulaic writing, it might still be able to produce a unique synthesis of existing styles—a feat DALL-E is certainly capable of in the visual realm:

I’m not claiming these pictures are amazing—but some of DALL-E’s creations undeniably are, and I hope you can see how the same mashup composition principle might be used to produce stylistically interesting writing.

In any event, this speculation is mostly beside the point for our purposes here. For the typical high schooler completing the typical English assignment, GPT-3 already offers huge advantages, and this will only grow truer in the years to come.

English Class 2073: Three Visions of the Future

Let’s consider three possibilities for the future of English class, in order of increasing desirability. (Note that these are not mutually exclusive but rather meant to paint a few broad categories.)

Vision #1: Obliviousness/Not Giving A Shit

Obliviousness/not giving a shit is the baseline to improve from. Some students are already using GPT-3 to write, after all—and schools are caught flat-footed, if they’re even aware. If there is any value in learning academic writing then this outcome is troubling and unacceptable. We can’t have students completely outsourcing an essential skill to robots!

Still, it’s worth asking: How bad is this, really? There are lots of formerly “essential” skills we already outsource to robots; and once the robots get reliable enough, we rightfully question whether the skills are actually essential anymore.

I remember, for example, a common refrain about GPS systems destroying people’s real-world navigation abilities. This charge strikes me as 100% true: I know I speak for many when I say that if you dropped me even just a few miles from my house, I doubt I could get back without a phone.

Yet the instances when I don’t have access to my phone + reliable service—or at least have access to someone else who can provide those things—are diminishingly rare. And just because we can conceive of hypotheticals in which navigation remains essential doesn’t mean the juice is generally worth the squeeze. (We can also conceive of hypotheticals in which CPR or identifying edible mushrooms is essential; do we expect everyone to know those skills?) If people enjoy navigating and get intrinsic value out of it, then of course they should continue to go without GPS! That doesn’t make navigation inherently useful in the modern world.

So while I’ve labeled “obliviousness/not giving a shit” as the least desirable of my three visions, this is really only true as long as there remain some aspects of writing it is necessary to teach the general population. In a (hypothetical) distant future of flawless AI prose, mourning the loss of useful human writing makes about as much sense as mourning the loss of wiping our asses with a sponge on a stick or making our own candles out of beef lard.1 In other words, if/when AIs outperform human writers by every measure, then it seems quite reasonable to stop caring about it as a skill: The people who want to learn writing for its own sake will do so, and everyone else will get by just fine.

Of course, GPT-3 isn’t at that point yet—and it’s quite a high bar to clear when you consider just how much is potentially involved in the writing process from start to finish (idea generation, research, sequencing/structuring, composition, editing/revision, etc., all done iteratively with an awareness of context and audience). Right now, students surely still derive value from learning to produce a clear, coherent argument and understanding how to craft sentences and paragraphs. Failing to teach them this skill is doing them a great disservice.

Vision #2: Contrived Anachronism

Again, it is helpful to look to analogies in other technologies.2 It has long been accepted, for example, that some math exams will forbid the use of a calculator—despite the fact that in the real world, students will almost certainly have access to calculators wherever and whenever they want. Why is this?

The most frequently cited reason is that students must first master the basics before they can solve problems using shortcuts. This deeper understanding allows them to check the computer’s answers and know how it got them. Admittedly there’s a logic here that applies to English class as well: If writing is a genuinely important skill that requires a lot of effort to learn (which it still is!), then some paternalism may be appropriate. Forcing students to write without GPT-3 is good for them.

Then there’s another less-acknowledged reason for restricting access to digital tools, one which I think weighs on people’s minds even if we don’t always admit it: Making a task more difficult makes said task a better sorting mechanism. For some reason, the powers that be are intent on placing everyone along a smooth bell curve of performance. If some assessment is a measure of “pure” ability, then—even if that measure has less and less external validity—then it’s potentially useful for figuring out where everyone falls on the curve. By this logic, forcing students to write without GPT-3 is a way to identify talent.

I’m a little sympathetic both these justifications—and I’m sure that in the coming years, we’ll see a dramatic rise in the use of in-class essays, internet restriction, and anti-cheating software. I think these strategies may well be a part of the solution, just as sites like turnitin.com serve as a deterrent against plagiarism now. But at their core, they also sidestep the question of What are we actually trying to accomplish in English now that GPT-3 exists? by responding “LA LA LA WHAT GPT-3 I CAN’T HEAR YOU.”

A more conscionable version of anachronism, I think, would be to home in on the aspects of writing that GPT-3 is bad at. With this knowledge, we could then design assessments that privilege those skills—which will necessarily be in higher demand in the future. Such assessments might not be “realistic”—just as practicing scales is not what you “realistically” do when you make beautiful music—but they could help isolate useful skills.

I’m not sure what exactly these assessments would look like, but one example that comes to mind is a “close reading” assignment, which asks students to provide hyper-detailed analysis of one specific passage (this in contrast to a broader thematic essay). In fact, close reading is arguably already a kind of guard against cheating: I’ve often given it as a final assessment for Shakespeare because I didn’t want students simply parroting back analysis from Sparknotes.

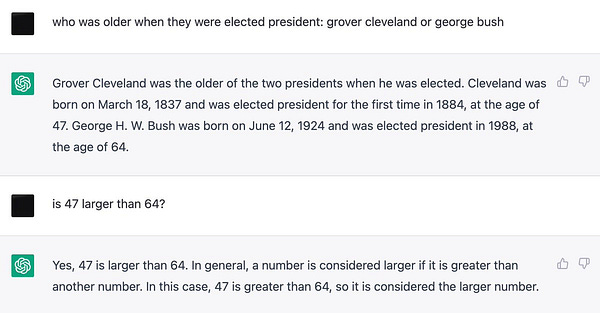

To my surprise, when I tested this theory out, ChatGPT actually did better at close reading than it did with writing a general Catcher in the Rye essay: Whereas it had previously hallucinated fake quotes, this time it successfully incorporated real lines from Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” speech—albeit not to very insightful ends. (I’m not sure if this improvement is because GPT-3 has been trained on a lot of writing about Hamlet, or because my instructions were clearer; I provided an example and copy + pasted the full soliloquy into ChatGPT.)

All of this goes to show the danger of trying to reverse engineer assignments that favor human strengths when the technology is improving so rapidly. If we do come up with something that GPT-3 can’t hack, who’s to say that GPT-4, -5, or -6 won’t be able to?3

There is, however, a third possibility—an approach to writing instruction that neither ignores the rise of this powerful new technology nor aims to restrict its adoption. What is this radical proposal, you ask? Just a little idea I like to call…

Vision #3: Make School Suck Less

Sometimes I’m astounded by the lengths to which schools go to crack down on cheating without ever stopping to wonder why students might be cheating in the first place.4

You might think that cheating occurs because—as one English teacher argued in a recent Atlantic piece about ChatGPT—“Teenagers have always found ways around doing the hard work of actual learning.” And sure, that’s one way to put it! But there’s another explanation here, one that is both more parsimonious and more generous to students: School sucks.5

Why exactly does school suck? For starters, attendance is compulsory, and leisure time is often filled with homework and extracurriculars. Freedom of movement—including when you get to eat and go to the bathroom—is highly restricted. And although the average teen’s body clock is delayed 1-3 hours later than adults, the average high school still starts at 8:00 a.m. (To translate: Biologically, high school is the adult equivalent of being forced to show up to work five days a week at 5:00 or 6:00 a.m.) Given this structural misery, you can understand why someone might take shortcuts to buy an extra couple hours of sleep and free time!

But for now, let's assume the basic parameters of the school day are here to stay and restrict our focus to the typical high school curriculum—which, also, sucks. I think this suckiness basically boils down to two factors:

Too much evaluation

Too little relevance

Regarding evaluation, I’ve written in the past about how grades distort the student-teacher relationship: By making assignments transactional, grades distract from the very skill they are meant to be assessing. (“Ok, Mr. Seckler, so if I rewrite this topic sentence then this would be an A- instead of a B+, right?”) They teach students to work only to the extent that work produces a desired outcome—and no further.

The key here is to separate the natural processes of learning and feedback from evaluation of the finished product.

If you believe that grades are necessary as either a motivational tool or a means of comparing students, I can assure you that this is not the case. At the very least, we could dramatically reduce the amount of evaluation and our students would be much better for it. After all, it’s patently clear that people are motivated to learn in many contexts where grades don’t exist—often more so than in contexts where they’re evaluated.6 (Did your soccer coach give you grades? Does your yoga instructor give you grades?) And if we insist on some mechanism to distinguish the best and brightest, this can easily be accomplished with one or two traditionally graded final assessments. (I’m willing to cede that we might want timed writing and/or anti-cheating measures in place here.)

To insist on traditional grades is to embrace one of the two dystopian visions I already described: Either you incentivize heavy reliance on GPT-3, or else you incentive teaching that is increasingly divorced from the skills students will use in the real world. If we want students to risk making mistakes—the source of their growth—then we need to stop penalizing mistakes. How can you expect someone to refrain from using GPT-3 when it provides such obvious benefits to them?7 It’s as if I told you I’d send you to prison unless you built a freestanding house of cards, then handed you the deck and a glue stick—all while stressing the importance of never EVER using glue to hold the cards up.

“What happens if I use the glue?” you ask.

“Uhh,” I say, “well, if it’s, like, really really gluey and I catch you then I’ll make you do it again. But I probably won’t be able to tell!”

Then I leave you alone in the room for twenty-four hours.

Now contrast this with a situation where someone is building a house of cards just for the sake of building it. It wouldn’t even occur to them to use glue! This is the learning environment I dream of: One where the technology is theoretically available to anyone who wants it, but no one uses it excessively because there’s no reason to do so.

Then there’s the relevance issue of English class—where to begin? Look, I enjoy reading novels and writing essays as much as the next guy, buttt…let’s just say there are only so many ninth-grade papers about Holden Caulfield you can read before you start thinking that maybe James Castle was onto something. I can’t imagine most students enjoyed writing these essays any more than I enjoyed reading them.

Now, I wouldn’t want to see novel-reading and essay-writing disappear completely from the English classroom, but it’s bizarre that they have such a stranglehold in the academic year of our Lord 2022-2023. Other than an occasional poetry or creative nonfiction unit, my high school students hardly ever read anything besides long works of literature; other than maybe one free choice project per year, they hardly ever wrote anything besides standard academic essays. (Maybe if I’d been braver, I could have pushed a few more interesting assignments—but not many.) Why are these traditional modes—novel-reading and essay-writing—so dominant? There are so many interesting genres and subgenres of writing out there: autobiography, thinkpieces, cultural criticism, prose poetry, flash fiction, explanatory journalism, and on and on! Exposure to the full diversity of writing that exists would not only increase student engagement; it would also be far more educational—both to consume and produce—than a focus on a single form.

Worse, still, the five-paragraph essay and its ilk teach students many of the wrong lessons about writing. This is a point Bruce Pirie makes brilliantly in his essay, “ ‘Mind-forged Manacles’: The Academic Essay” (bold text mine):8

What does the five-paragraph essay teach about writing? It teaches that there are rules, and that those rules take the shape of a preordained form, like a cookie-cutter, into which we can pour ideas and expect them to come out well-shaped. In effect, the student is told, “You don’t have to worry about finding a form for your ideas; here’s one already made for you.” This kind of instruction sends a perversely mixed message. On the one hand, it makes structure all-important, because students will be judged on how well they have mastered the form. On the other hand, it implies that structure can’t be very important: it clearly doesn’t have any inherent relationship to ideas, since just about any idea can be stuffed into the same form.

That, of course, is not right. Structure isn’t an all-purpose predesigned add-on. Ideas don’t come neatly packaged in sets of threes, and they don’t line themselves up in orderly patterns of point/evidence/explanation. Indeed, the most common symptom of five-paragraph essay writing is the student’s heavy-handed attempt to make unwilling material fit those three obligatory body paragraphs. The student is forced to chop ideas into three oddly shaped or clumsily overlapping chunks, like Cinderella’s sisters trying to squeeze their toes into someone else’s shoe.

Writing, at its core, is a matter of finding and making the shapes of ideas, not a matter of cramming ideas into a universal pattern. Well-intentioned teachers believe they are giving students a helpful boost by handing over a prefabricated structure, but they may in fact be denying students the opportunity to do the very thing that writing is all about—making order, building a structure for the specific ideas at hand. In an important way, those students are not doing real writing. They are creating clever, almost lifelike facsimiles of writing, but a key element is missing: they have never asked themselves, “What shape is demanded by what I am trying to say?”

In fact, writing my own essays for Substack has forced me to confront just how little resemblance the way I often taught writing bears to the way I typically produce it. Anecdotally, I do know of some writers who seem to work as the traditional model would suggest: They create an outline, then fill it in with the fully formed ideas that are already in their head. But far more often, writing involves circuitous stretches of discovery and reverse outlining. The writer does not know what they think until they see what they say. It’s not that the traditional model has no validity whatsoever but that it elides the true subtlety of iteratively toggling between macro structure and in-the-moment generation of new language/ideas.

Why, then, does the emphasis on formulaic writing persist? The reason is simple: Formulas are clear and scalable. When you have over a hundred students, a one-size-fits-all model of excellence is not just easier to teach but, frankly, often the only viable option given constraints of time and curriculum. Of course the best way to improve student writing would be to tailor instruction individually to their needs; since that’s usually not realistic, it makes sense to cast a wide net by focusing on the skills that many students really do need practice with: clear paragraphing, academic conventions, etc.

In this area, some valuable fruits of GPT-3 may be sown in the very problem it has created: The same technology that allows students to feign independent thought is one that can be used to better individualize instruction. In this utopian vision, GPT-3 serves not to undermine education but to supplement it, by giving everyone their own private tutor. (Of course, we first need to be confident that it’s giving accurate answers):

I don’t know exactly what this looks like at scale, but I do know that for far too long, the presumed necessity of academic writing has been used as an excuse to make it miserable. Now, finally, we have the technology to manage the more tedious aspects of prose production, and to truly meet people where they’re at. Will we respond to this technology by ignoring/suppressing it? Or is it possible we’ll return to first principles of why people read and write in the first place?

When Robots Outwrite Humans, What’s Left for Us?

Perhaps the vision I’m describing sounds naive to you. Perhaps the (complete or partial) elimination of grades strikes you as a lowering of standards, and the upending of traditional English curricula sounds chaotic.

Well I’ve run the experiment, and it works.

This past fall, I had the opportunity to teach a seminar for first-year undergrads called “Has the Internet Destroyed Writing?” This was an incredible treat in large part because I was not bound by the strictures of traditional high school English, and because the university actively encouraged interdisciplinary teaching. Accordingly, I gave students the freedom to blog about whatever topics they wanted, so long as they tried out a variety of formats; and of their five posts, all except the final one were graded pass/fail.9

If I were to teach this class again, there are many things I would do differently—but the basic design of the writing assignments is not one of them. While I had feared that students might take advantage of the pass/fail grading and phone in the work, the instances of this were no more frequent than under a traditional grading system. Most students showed far more engagement and improvement than I’ve seen in the past—a theme that came through strongly in student feedback at the end of the semester, such as this reflection:

I enjoyed this class a lot more than I expected. I thought it would be a boring class about writing and how the internet has ruined books, and we would read many books and papers. I’m glad that it wasn’t even close to that. Implementing blogs instead of essays is one of my favorite things in any writing class. It was a lot more informal, and I got to have more fun with it than I would have for an essay. Writing my blog was fun, and it didn’t take too much time to write 500 words a week. I got to explore ideas I had thought about before but was never motivated to dive deeply into them. I got to write about what I am passionate about, which helped spice up the class more than usual…This class helped me learn that writing is a tool I need to use more often. For my blog posts, I repeatedly stated things that had happened to me, how that’s affected me so far, and whether or not they were good. It was nice to write them down. I didn’t realize how calming writing could be when you are writing about something you are passionate about.

Or this one:

The biggest thing that stuck out to me was I wrote a lot more confidently in this class because of how much more freedom I had. When I was writing about a topic I chose and knew that it would not be graded harshly allowed me to be more creative and experiment more than I normally would on an essay for a regular class.

Or another:

Being able to create my own personal blog about something that I love was hands down my favorite assignment I have ever done as a student. You gave us the freedom to write about something that we love, rather than forcing us to do an assignment about something we have no interest in and was a burden to do.

These examples are hardly cherry-picked—they’re sentiments that came up again and again in student feedback—and I share them not to boast but as proof of concept: Given the right opportunities, students require neither the incentive of letter grades nor the scaffold of rigidly established forms in order to produce good work. (It’s also worth noting that this was a random first-year seminar, not restricted to English majors; I don’t think this response was just a case of self-selection.)

I wasn’t worried about students cheating on these writing assignments because there was hardly any upside to doing so. When your post is graded for completion and you can do it on whatever topic you want, what do you really have to gain by using GPT-3 (other than, maybe, a couple hours of saved time)? In fact, I was so unconcerned about cheating that I actively introduced students to GPT-3 in class and had them play around with it.

Remember, just because students aren’t being traditionally graded doesn’t mean they aren’t getting feedback. I gave students far more feedback on their four pass/fail posts than on their traditionally graded final post, and always selected a couple to shout out publicly. (Indeed, whenever I emphasized an effective student technique—e.g., good graphics, a strong narrative hook, etc.—I was almost guaranteed to see many other students trying it in subsequent posts.)

I realize that what I’m proposing is less actionable at the high school level than at the college one, and that the reforms I’m proposing won’t happen overnight. But they represent a goal to move towards directionally. And again, the three visions above are not mutually exclusive; surely, the real future of education will include elements of all three.

The only certainty of GPT-3 is that it will force us to adapt. If Large Language Models excel at clarity and copyediting, for example, then those skills are of relatively less value; this doesn’t mean utilitarian forms of writing will stop being important to a functioning society, but they may no longer be quite so important for everyone to learn.10 If the average person wants to draft emails, memos, contracts, etc. with an AI, then so be it! This will only free up brain space for those facets of writing that are the sole purview of humans.

And what, you ask, are these exclusively human virtues of writing?

As so many have observed, writing is a form of thinking: In producing it, we organize our minds. In consuming it, we encounter other minds—arguably more directly and authentically than in any other medium. These are functions that can certainly be aided by a computer, but they can never be filled by it. (Consider, for example, the absurdity of a prompt like: ChatGPT, write 2,000 words processing my feelings about my wife Sherlane leaving me for my best friend Lance.) At best, an AI can respond with questions to help spur introspection, or suggest words that we affirm/deny as accurate reflections of our experience.

Again, an analogy to visual art may be helpful here. As

explains, the perceived threat DALL-E poses to illustrators is actually an issue that played out in a previous generation with the invention of photography:The better that AI gets at creating artwork that perfectly represents visual reality, the more valuable art that instead fixates on the depiction of human interiority will become. AI art simply replicates the crisis of representation—the value of being able to paint beautiful representations of reality falls as a computer can ape those skills through machine learning. But this leaves art that foregrounds the artist’s emotions even more valuable.

As social creatures, we have an intrinsic desire to know others and be known by them; this is the north star by which English teachers should be guiding their students. In the long-run, after all, success at writing is predicted not by mastery of formulas and conventions but by simply wanting to write a lot.

So when robots reign supreme, what’s left for us? If we don’t fuck this up—and lord knows that’s a big if—then perhaps we humans will be left with just the very best parts of writing: the tender thrill of empathy; the sweet alchemy of newfound insight; the dogged assertion of deeply held beliefs.

TL;DR

Generative AI reduces the value of some aspects of writing (i.e., copyediting, summarizing information) relative to others (i.e., facilitating contact between two minds).

An education system that is responsive to this will increasingly emphasize the latter humanistic goals.

Thanks to Charlie for edits on this post and OnceUponABot clips.

Note, again, the distinction between writing that is useful and writing that is beautiful or meaningful to create. Electric lighting is a more cost/energy efficient than candles, and has therefore become the default modern option; still, many people frequently use candles for purely aesthetic reasons, and a smaller subset still make candles for fun.

For other possible analogies to GPT-3, I enjoyed this list of thirteen other historically disruptive technologies by Dynomight.

GPT-4, due to be released in early 2023, is rumored to be a freakishly significant improvement on GPT-3. (Perhaps it will even be available by the time you’re reading this!) Also, for what it’s worth, ChatGPT is technically GPT-3.5—a half-generation ahead of GPT-3.

As a student teacher, I worked at a school that used a software—ominously called “GoGuardian”—which allowed me to see what was happening on the display of all my students’ Chromebooks simultaneously.

I say “school sucks” as someone who mostly enjoyed high school and did well in that environment. I just know, having been in far better learning environments, how far it is from the ideal. And I know as a teacher that most students—even the high-performing ones—are usually motivated as much by extrinsic sticks and carrots as by any innate desire to master the subject matter.

Many studies have demonstrated that extrinsic rewards decrease intrinsic motivation—most famously: Children given a reward in exchange for drawing become less likely to draw on their own.

This is especially true of low-performing students—who, in my experience, are the ones most likely to cheat, out of necessity.

In fact, this is a piece shared with me by my own tenth grade English teacher, just about the only thing I remember from that particular class!

I’m hardly the first person to advocate for this kind of approach. In particular, I am grateful to author and veteran teacher Linda Christensen whose book Teaching for Joy and Justice first gave me permission to not grade student papers; and to instructors of my own who inspired me with “menus” of open-ended pass-fail assignments, such as Thalia Field, Michael Stewart, and Barbara Tannenbaum.

It is believed that writing systems first developed for the purpose of economic accounting.

Well said, human.