Here’s a study I think is pretty revelatory: In an introductory Harvard physics course, students were divided into two groups. The first group got a lecture from an excellent instructor—one who worked through problem sets in real time as students followed along on their own copies of the worksheet. The second group was told to first try the problems on their own in small groups, and only then did the instructor show them the solutions.1

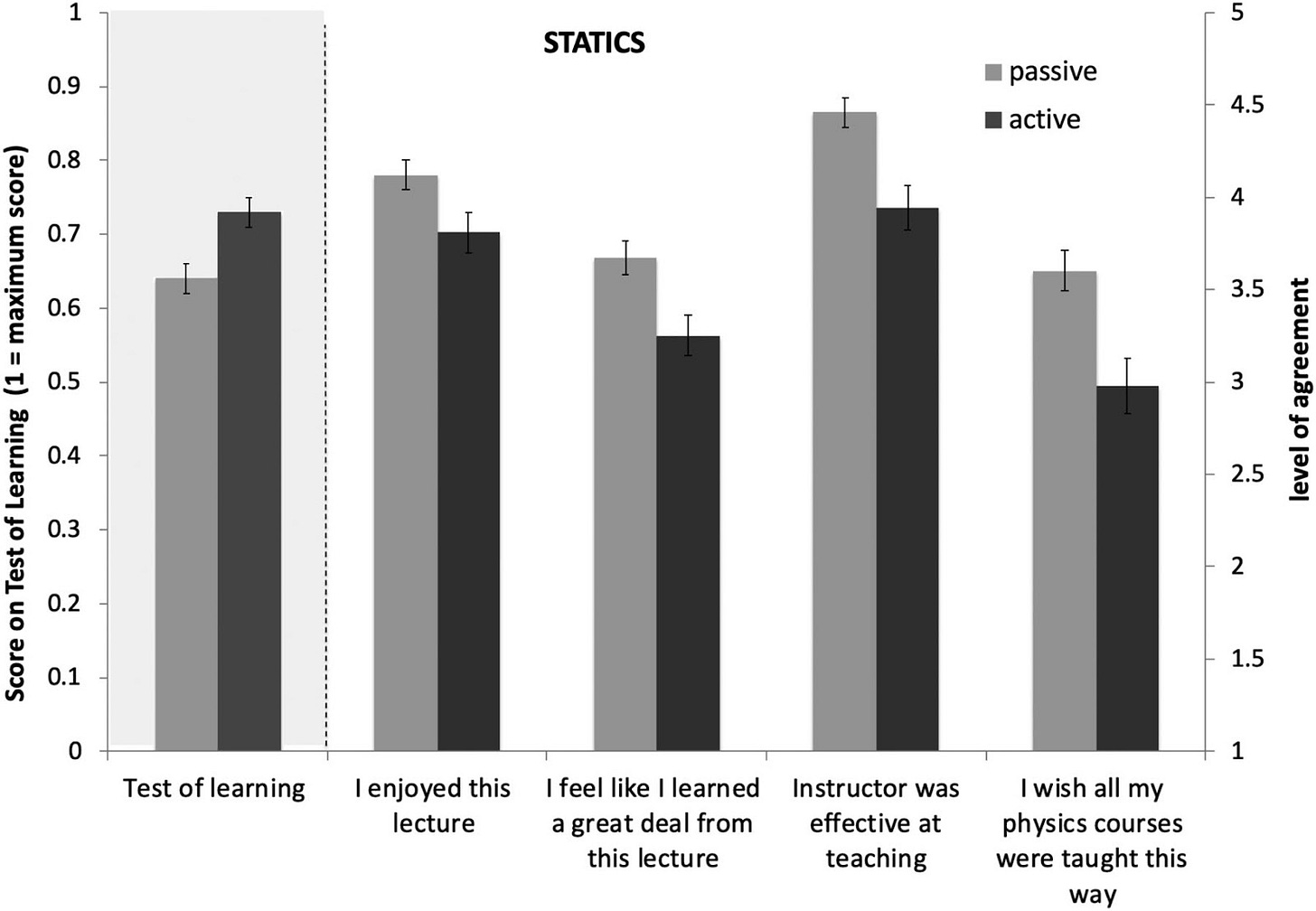

You can probably guess half of the headline result. The relatively active learners (i.e., those who tried the problems on their own first) learned more than the passive ones. But there’s a crucial catch here: Compared with the group that just received the lecture, the active learners felt as if they had actually learned less.

In other words, believing that you know something isn’t a very good predictor of how you’ll really do on the test.

A clear, knowledgeable speaker walking you through material elicits a feeling of fluency—one which the brain tags as “I understand this!” Conversely, struggling through problems you haven’t yet been taught to solve elicits a feeling of effort or frustration, which the brain tags as “I’m stupid!” And indeed, on paper, the active learning paradigm seems less efficient: If the professor is eventually going to walk through the solution regardless, why build in the fumbling around period at all?

The answer, as these study results demonstrate, is that the fumbling period actually primes you for deeper understanding. No doubt there are various mechanisms at play here. (To name two: Simply spending with an idea makes it more salient and easier to recall; and when an expert walks you through a solution—even one that seems perfectly comprehensible—they gloss over subtle assumptions and choice points you would have been forced to grapple with on your own.) Whatever the explanation, this is a case where an activity that doesn’t look or feel very “productive”—at least in the short-run—demonstrably improves performance.

I believe that human achievement in most domains operates like in this study: The real work—the cognitive heavy lifting—is that which is least visible. Usually, it registers as a kind of pre-work: an exploration period which surfaces sub-problems, implicit frames, and gaps in knowledge but yields few or no deliverables. Though its exact form will differ between projects and individuals (I’ve referred to it in the past as “Phase 1” of the S-Curve), it includes activities such as reading, sketching, freewriting, prototyping, brainstorming, and unstructured conversation.

This exploration can at times feel effortful—as it did for students in the study—but it can also occur in a more playful associative state.2 That’s especially true when we recognize the exploration for what it is: a crucial reorganization of the mental map we’ll use navigate forward. Instead, far too often, we Goodhart ourselves with the appearance of progress; we believe that if we are not actively putting words on the page, or adding lines of code, or making a sale—or however our success will ultimately be measured—then the work doesn’t “count.” This is misguided and counterproductive. It is mistaking external evidence of understanding for understanding itself.

It isn’t that pre-work (or “Phase 1,” or whatever you want to call it) yields no evidence of progress. It’s just that the “evidence” isn’t generally very impressive or legible to outside observers. It might simply be doodles on a napkin, or a notes scribbled in the margin of a book, or a list of unanswered questions and to-do items. Unlike the final product which is an end in and of itself, these artifacts are byproducts of a process happening entirely inside the mind. Optimizing for them makes about as much sense as optimizing for a full lint screen when doing your laundry: Lint may well be a sign that the cleaning process was successful, but it’s hardly the purpose of a washer-dryer.3

The blessing and the curse of true mental progress is that only you can really assess its quality. To maximize your long-run understanding, you therefore must learn to distinguish the feeling of knowing something from merely knowing its name; to be honest with yourself about when you are engaging in deliberate practice versus just going through the motions; to silence your inner manager (the one who, especially in the early stages of a project, can grok only imperfect proxies for progress) and instead cultivate your inner eye.

To make the experimental design more sound, the groups actually swapped instructional modes halfway through the course, as shown in Table 2 (i.e., those that got just lecture at first then did the active learning paradigm, and vice versa). For simplicity, I’ll just refer to one “active” group and one “passive” group.

One term I like here: “soft fascination”—a relaxed attentional mode, often experienced in nature, which is conducive to mind-wandering and unexpected creative leaps.

I do think time spent is decently correlated with “useful mental effort”—but of course time alone is an imperfect proxy, and therefore, again, subject to Goodhart’s Law.