[T]he magician is one of the few true artists left on earth, for whom the mastery of technique means more than anything that might be gained by it. He center-deals but makes no money—doesn’t even win prestige points—because *nobody knows he’s doing it.* –Adam Gopnik, “The Real Work”

For the last few months, I’ve been on a bit of a magic kick. No, I’m not talking about Harry Potter, and I’m not talking about the Gathering™—I’m talking about professional illusionists like David Blaine, Penn & Teller, and Harry Houdini.

One thing that quickly becomes apparent when you start reading articles about magic, and watching the Conjurer Community YouTube channel, is that professional magicians don’t refer to the basic unit of their craft as “tricks.” They instead talk about “methods” and “effects”: the techniques and technologies the performer uses, and the resulting experience that the audience has, respectively.

This language of methods and effects is itself a powerful way of looking at the world, one which speaks more precisely to the skill and psychological dynamics at play in magic. It is also the starting point for a rich set of ideas with implications for other domains. These ideas are…

1) Methods may precede effects.

2) Mysterious methods trump opaque methods.

3) Sometimes the “mystery” of the method is just an insane amount of effort.

4) There’s no such thing as a “half-finished” piece of magic.

…and, most importantly:

5) One “effect” ≠ one method

Let’s explore each of these ideas in the context of magic, and then consider how they generalize to the rest of life.

The Magic of Magic

1) Methods may precede effects.

On This America Life, Teller, of Penn & Teller fame, describes how he once became interested in a trick invented by the magician David P. Abbott in the 1920s and 30s.1 The trick involved a clever method for manipulating a ball on an invisible thread, so that the ball appeared to be floating. Teller tracked down Abbott’s description of the trick in a posthumously published manuscript, recreated the method, and practiced it for months, perfecting his technique.

As he practiced, Teller’s version of the trick began to morph. He got an idea that instead of having the ball floating, he could put it on the ground. Rather than a silver ball like the one used by Abbott, he swapped in a red kickball, and staged the routine in a playground setting. Finally, he showed it to his partner Penn with the idea of adding it to their show. Penn was unimpressed:

I remember Teller getting a little bit mad at me [Penn]. Because I said, “What's the idea behind this?” And he was very offended. He was like, “Well, the idea is the trick.”

But of course “the trick” is how audiences think about magic. To magicians, there is not a single trick; there is a method and that method’s effect. Teller had an original method, but the effect wasn’t coming through (at least for Penn). In Teller’s words:

I think it hadn't clicked with [Penn] because it lacked an essential dramatic idea. Of course, to me, I was all wrapped up in the idea that it was a floating ball that wasn't floating, which isn't a very good idea. I mean, that's not an idea that communicates to an audience.

Eventually, another magician friend suggested treating the ball like a dog that is resistant to training. This tweak—which imbued the routine with a tiny bit of narrative tension—turned out to be the missing ingredient. All in all, Teller worked on the trick for eighteen months before it finally was ready for their show.2 Here’s the finished version:

I find this story intriguing because it suggests that a magician can work on a method without a clear sense of what the final effect even is—though this isn’t necessarily preferred. As Penn once told the Harvard Business Review:

People say to me, “How can I make this particular idea play in front of the audience?” But if they’re phrasing the question that way, they haven’t got a chance. It has to be “I have something I desperately want to say. How do I say it?” Then it comes down to mechanics.3

But you don’t always have to start with a desired effect, as the ball-and-thread routine shows. Looking back on how he developed the trick, Teller chokes up a bit when telling Ira Glass, “I do trust my gut. This trick that we do in the show is not the trick that I thought we were going to do…But it is the trick that was calling out to me. You know?”

2) Mysterious methods trump opaque methods.

What makes some magical effects mesmerizing while others fall flat?

One answer is that the boring effects just seem like random miracles, lacking any apparent cause—or else they leave too many open possibilities in the audience’s mind to be truly dramatic. The good effects, by contrast, give the audience just enough to be able to speculate about the method. As Teller describes:

One of the things that you do as a magician is you try to put yourself in the position of the audience at every moment. And you say, what would I be thinking at this moment? And you try to manipulate that. And one of the ways you do that is by giving the audience a little chance to figure something out, and then take it away from them.

In the ball-and-thread trick, for example, the ball starts in contact with the bench (a plausible control mechanism), then seems to be controlled by Teller’s finger—and only then, finally, moves freely through the air without any obvious external stimulus.

This talent—for not only inventing methods but for selectively suggesting and foreclosing methods in a given routine—is an art in and of itself. In an essay called “The Theory of False Solutions and the Magic Way,” the Spanish magician Juan Tamariz likens the viewer’s experience to labyrinthine painting full of dead ends. As one profile of him explains:

The spectator rides on a carriage pulled by two horses, one winged and one earthbound. The path takes various turns, some of which represent false solutions—any idea the spectator may come up with for the method behind the effect. The magician must prevent spectators from entertaining even the false solutions, in the process of leading them away from the real one, too—leaving the impossible as the only logical explanation.

Sometimes, the red herrings in a magic routine can be quite dramatic. The most extreme version of this I’ve come across is an episode of Penn & Teller: Fool Us, a show in which the titular duo tries to guess at the true methods being used by guest performers. In the clip below, a magician named Asi Wind seems at first to explain the entire mechanism behind his routine—including a trick table with a secret trap door and an internal carousel of card decks, controlled by a magnet on his coffee mug:

“I wanted you to feel for a brief moment what it’s like to be on my side of magic,” says Wind. “For a brief moment to enjoy the part that I find beautiful”—before a secondary reveal that the “carousel” he showed is in fact just a picture of many decks of cards. The true method remains a mystery, and Penn and Teller are utterly bamboozled.4

At the same time, this obsession with misleading audiences is perhaps misguided—per Teller:

If you understand a good magic trick—and I mean really understand it, right down to the mechanics at the core of its psychology—the magic trick gets better, not worse.

3) Sometimes the “mystery” of the method is just an insane amount of effort.

“There’s no better partner than Teller,” Penn once said:

He’s not the smartest or most creative person I’ve ever been around, but he’s the hardest working. He will not give up; you can put him on a simple task and in the middle of it hit him with a baseball bat square in the face, and he goes right back to the task.”

Teller, for his part, has a pithier take on his own talents: “Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.”

As one example of this principle, tech founder Allen Pike recounts a trick in which Teller produced a specific playing card by leading viewers to a nearby park, digging a hole in an undisturbed patch of grass, and miraculously uncovering a box that contained said card. How did he do it?

To create this magical moment, [Teller] had to do something you wouldn’t expect: he’d gone out into the park and buried a number of boxes, corresponding to potential cards one might choose. Then, he waited months—until the grass had grown over. Only then could he perform the trick.

Deducing what card you’ve picked is a well-known sleight. But performing a trick where your card is seamlessly buried requires so much advance preparation that it seems impossible.5

Teller’s method in this example may strike you as alternately amusing or frustrating, depending on your mood, because it seems to require no special talent. Once you know the secret, you think “Oh, I could have done that.”

David Blaine, by contrast, has become known for doing “tricks” whose requisite effort is so extreme that you think, “There’s no way I could have done that.” These include stunts like like eating glass, holding his breath underwater for 17 minutes, and sticking a needle through his arm. In these cases, the “trick” is that there is no trick; the trick is that David Blaine is legitimately insane.

Or as Blaine told New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik: “I don’t want magic that looks real. What I want are real things that feel like magic.”

4) There’s no such thing as a “half-finished” piece of magic.

At one point when Teller is describing his practice sessions with the ball and thread, podcast host Ira Glass asks why he didn’t show the trick to Penn earlier on. Teller explains:

You can't look at a half-finished piece of magic and know whether it's good or not. It has to be perfect before you can evaluate whether it's good. I mean, magic is a fantastically meticulous form. You forgive other forms. A musician misses a note, moves on, fine. He'll come to the conclusion of the piece. Magic is an on/off switch. Either it looks like a miracle, or it's stupid.

This is the dark side of “methods may precede effects”: You can invest a lot of time in a trick and still not know definitively whether it will be successful. The only way to flip the switch from “off” to “on” is to put in what Adam Gopnik calls “the real work”:

Just as chefs know that recipes are of little value in themselves, magicians know that learning the method is only the beginning of doing the trick. What they call “the real work” isn’t the method, which anyone can learn from a book (and, anyway, all decent magicians know roughly how most tricks are done), but the whole of the handling and timing and theatrics of the effect, which are passed along from magician to magician and from generation to generation.

I think that Teller’s own account of the ball-and-thread trick actually undermines the “on/off switch” claim a bit. (More on that later.) But the insight that more than half the work may take place before a magician has anything to show for it is worth noting.

5) One “effect” ≠ one method

Suppose you’re a magician trying to produce a specific playing card an audience member has named. How might you achieve this effect?

In fact, there are many methods that could produce such an effect—for example:

You could pre-stack the deck in a set order that you’ve memorized.

You could use sleight of hand to sneak the named card in where you want it.

You could use a marked deck that lets you identify cards from their backs.

You could use a precise shuffling technique that gives the appearance of reordering the deck without you losing track of the named card.

You could have used some kind of nudge or unconscious suggestion to get the audience member to name the card you wanted.

You could be relying on a stooge who was planted in the audience and is actually a confederate in the illusion.

No doubt all of these methods have been used by different magicians in different times and places, and there are more clever methods than the ones I’ve named. My point is just that when executed properly, these methods are all more-or-less equivalent from the perspective of the audience: Someone has named a card; the magician has made said card appear.

This, as far as scholars of magic can tell, is the key insight of David Berglas, creator of the “holy grail of card magic.” His trick, the famed Berglas Effect first requires an audience member to name a random card and a number from 1 to 52 (indicating a serial position in the deck); Berglas then conjures the card at the specified position without ever touching the deck.6 This trick—sometimes called a touchless “any card at any number” or “ACAAN”—implies a staggering number of permutations, with none of the magician’s standard means of physical manipulation. How does Berglas do it?

Well, a magician never reveals his secrets—but there is of course speculation. The leading explanation, as described by journalist David Segal, is that the Berglas “Effect” is in fact not a single trick at all; it is a multiplicity of methods deployed toward producing the touchless ACAAN under different circumstances. Berglas may, for example, be using multiple decks, psychological manipulation, and a variety of “outs” to ensure that he is never backed into a corner in his act. Or in Segal’s words:

Mr. Berglas is nothing if not a masterful improviser and a born gambler. What seems like a cohesive performance is actually a high-wire display of spontaneity with a heavy overlay of psychological manipulation.

In his profile of Berglas, Segal recounts how, when he visited Berglas at his home and asked him to perform the famous trick, Berglas grew indignant—before later seeming to soften and acquiesce. “I’ll take a chance,” he said. “I might be off by two.”

Segal dealt the cards.

In the end, Berglas was one off: Segal had chosen 44 as his number, but his card (the seven of diamonds) appeared at the 43rd turn. Segal muses on the meaning of this outcome:

Off by one seems, on some level, more perplexing than nailing it. Off by one implies that there is nothing automatic about this ACAAN, that it isn’t a contraption that simply works when deployed. It’s more like archery, which requires practice and concentration and can end with something other than a bull’s-eye.

You can watch a late-in-life performance by Berglas below, including commentary by other professional magicians on how he subtly controls the situation. (His famous effect appears at 24:34).

The Magic of Life

We’ve covered a number of powerful insights from professional magic. Let’s now consider how they apply to other domains.

The first idea, that methods may precede effects, is a rich analogy for all kinds of desirable outcomes. Comedians may spend months or years working out material before it becomes consistently funny. Science is riddled with examples of experimenters who, relying mostly on curiosity and close observation, stumbled on discoveries of great consequence. You could call this luck or intuition or conscious exploration; under any name, the approach clearly bears fruit, at least some of the time.

What exactly are the “methods” that effect unforeseeable success? I’ve written about this in the past somewhat impressionistically,7 and I’ll likely have more to say in an upcoming post. In the most general form, I think they tend to be behaviors that are sustainable, intrinsically rewarding, and have asymmetric upside—“methods” like:

Continually learning

Building strong relationships

Reliably tracking and completing tasks

These methods are almost always necessary for conjuring success (e.g., outsized skill, wealth, fame, or impact) though they are certainly not sufficient.

In magic and life alike, the notion that mysterious methods trump opaque methods means that we are most likely to appreciate a great performance when we have some idea of how it’s done. For me, great improvisational jazz or comedy are perhaps the best embodiments of this: I feel almost giddy trying to square the seeming impossibility of the performance (“I can’t believe that wasn’t rehearsed!”) with my own knowledge of the techniques that of course did go into inventing it on the spot.

By contrast, when I see high-level curling, or textile production, or people balancing on slacklines, I may find the performance beautiful and/or impressive; I understand intellectually that it required extensive practice and; but it rarely feels magical (to me) because the method is more-or-less a black box.8

At the same time, if a performance is too skillful and we know exactly how it’s done, it can sometimes feel flat. As Adam Gopnik explains:

Magic works best when the illusions it creates are open-ended enough to invite the viewer into a credibly imperfect world…In every art, the Too Perfect theory helps explain why people are more convinced by an imperfect, “distressed” illusion than by a perfectly realized one. A form of the theory is involved when special-effects people talk about “selling the shot” in a movie; that is, making sure that the speeding spacecraft or the raging Godzilla doesn’t look too neatly and cosmetically packaged, and that it is not lingered on long enough to be really seen…Illusion affects us only when it is incomplete.

Similarly, a passionate but rough-around-the-edges recording is often more moving than a highly produced one, and “credibly imperfect” styles of painting (impressionism, surrealism, cubism, etc.) are generally more interesting to look at than photorealistic portraiture.

The importance of grit or 10,000 hours for developing expertise has become something of a trope in the last decade. That doesn’t make their proponents any less correct, though—and still many of us struggle to resist the allure of clickbait touting “one quick trick” to catapult our fitness, relationships, or careers. The sad truth is that very often there is no trick. Sometimes the “mystery” of the method is just an insane amount of effort. Allen Pike riffs on the parallel here with magic:

The pianist whose fingers seem supernaturally nimble, the presenter whose message seems viscerally compelling, and the artist whose paintings seem impossibly realistic all wield the same magic: they’ve invested more time than you’d expect.

It can be difficult, psychologically, to commit yourself to spend an extreme amount of time and attention towards a goal, no matter how worthwhile. Doing impossible things feels, well, impossible.

The reality that most desirable skills require an insane amount of effort is both comforting and sobering: comforting because it offers a recipe for success that is—at least in the abstract—quite simple; sobering because that simple recipe is not remotely easy to implement.

I’ve already hinted at my skepticism toward Teller’s claim that there’s no such thing as a “half-finished” piece of magic. Teller argues that this binary “on/off” quality of magic is one of its distinguishing features as an art form. I think he is directionally—but not literally—correct.

In fact, there are many domains where “half-finished” is good for almost nothing. A gymnast can’t complete half a flip; a computer program either runs or it doesn’t. In general, any performance in which the ultimate outcome depends on a specific, linear sequence of events is likely to fall into this category: All it takes is one broken link, and the whole chain fails.

Teller’s claim is also somewhat undercut by his own narration of the ball-and-thread trick. Arguably, he did at one point have a “half-finished” trick, in that he’d developed a whole playground-themed routine that Penn didn’t give the green light. (Actually, Penn also didn’t like the version of the trick that eventually made it into their show.) All this goes to show that “finished” and “magic” are in the eye of the beholder: Whether a performance “works”—in any domain, I’d argue—is really a question of working for whom.

The more precise but less catchy version of Teller’s insight is that progress toward magic does not scale linearly with effort. You can work on something for a long time before you see rewards, and then experience sudden explosive growth. This isn’t quite an “on/off” switch—but it can certainly look like one from the outside. For this reason, Teller is absolutely correct that we should exercise humility when judging work or talent in its early stages of development.

There’s More than One Way to Pull a Rabbit

The last idea, that one “effect” ≠ one method, is significant enough to warrant a section all its own.

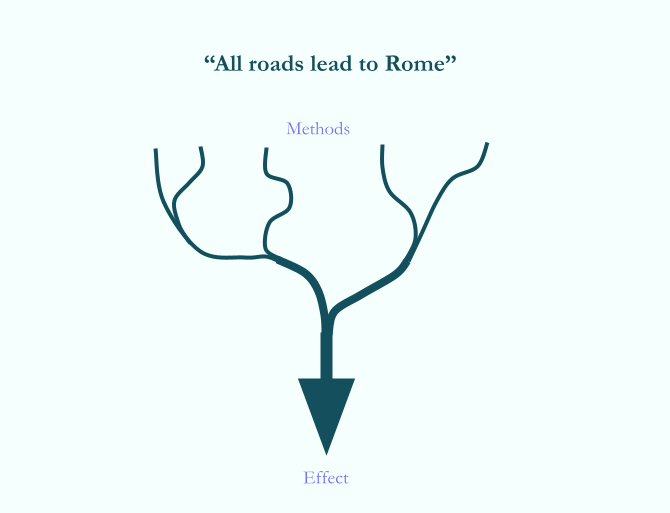

Let’s again take “effect” broadly, as a stand-in for “anything you might want to accomplish.” This could be as small as unclogging a drain or choosing an outfit for work; it could be a big life outcome, like becoming a doctor, founding a startup, or playing in the NBA. At first glance, the lesson of the Berglas Effect in all of these cases is simple: There is more than one method which will produce the desired outcome—a situation we could depict like this:

To take the simple case of unclogging a drain, for example, you could use Drano, use a plumbing snake, or call a professional. Pick a card, any card.

At the same time—especially with big life outcomes—it is far from true that all methods you might try inevitably converge on the same effect. Choices compound, and possibilities branch endlessly into the future. In some sense, this is the opposite of the picture above:

On closer inspection, the true picture of the Berglas Effect—and the one that serves as the best analog for other domains—turns out to have elements of both these representations. Actions do have consequences, of course, and life is path-dependent; but most outcomes are multidetermined, arising from a variety of possible causes and paths.

In other words, there is not a single “become a doctor” effect—let alone a “found a startup” effect or “play in the NBA” effect. But among the variety of possible methods some are much likelier to produce the desired “effect” (e.g., learning to code is generally more conducive to entrepreneurship than learning to speak Russian); and some paths may be foreclosed by a failure to take certain actions (e.g., whatever other methods you use to become a doctor, the MCAT will surely be necessary).

Similarly, David Berglas—the best in the world at producing the “effect” which bears his name—still seemingly can’t perform it with one hundred percent reliability. Once the wheels are in motion, the complex machine he’s built may still veer off course. At the same time, he has many many tools at his disposal to steer toward the desired effect—a dynamic method that adjusts his route in realtime. He is both highly skilled and highly opportunistic.9

If we accept that many desirable life outcomes are like this characterization of the Berglas Effect (improbable, comprising multiple inputs, and tractable on the margin) then a few insights snap into focus:

First, it is clearly not the case that anyone can achieve anything. Berglas has outs in his act for a reason: Not every situation that arises is conducive to his effect. Similarly, not everyone has the talent, grit, or genetic allotment that will allow them to make it to the NBA.10

Second, success is combinatorial. Just as Berglas is leaning on a variety of methods to produce his effect, someone might make it to the NBA by being freakishly agile, exceptionally tall, or a machine from the three-point line.11 They might be ninety-fifth percentile in all of these areas, or an outlier in two out of three. “Magic,” in this respect is a question of recognizing what particular gifts you’re blessed with and using those methods toward a desired effect.

Finally, even when the odds of success are low, there are actions you can take to increase their likelihood, and the more bites at the apple the better. Berglas’s talent lies not in a single master technique but rather in knowing how, at every point, to maximally tilt the situation toward his ends. Do this enough times and the odds get pretty good the effect will happen at some point12—even if there’s never a guarantee. Similarly, height, athleticism, and work ethic are no guarantee of making it to the NBA; but any individual high on all three of these traits is way likelier to make it to the league relative to the general population, and can consciously improve the latter two.

Coda: The Method Is the Magic

In this post, we’ve seen several philosophies for how methods and effects might interact: methods in search of an effect, and effects in search of methods; methods so brazen they seem impossible, and methods so subtle, so deliberately misleading, that they make the effect all the more powerful; “effects” that are in truth a variable combination of methods, skillfully curated toward the illusion of a repeat performance. With so many different approaches and schools of thought, it can sometimes seem there is no underlying principle of professional magic: Are Teller’s floating ball, Berglas’s subtle manipulations, and David Blaine jabbing a needle into his arm really all the same art form?

I believe the answer to that question is yes, and that this “yes” underscores magic’s greatest lesson of all. The common invisible thread among all these performers is an obsession with method.

An obsession with method—with the precise mechanics of how things are done—is profound because it is available to all of us, all the time. Perhaps you have a vision of success and just need to figure out how to get there. Perhaps you just have the beginnings of a technique and a vague intuition of where it might lead. In either case, the path is clear: practice, iterate, catalog effects. An unreasonable amount of time. This is the secret hiding in plain sight, the “real work” of magic: The method is the magic.

Additional Reading

I am in no shape or form a professional magician, so I’ve leaned heavily on others’ accounts of the craft in order to write this post! In particular, I found this New Yorker piece and this episode of This American Life immensely insightful; if you enjoyed the post, you might enjoy those as well.

Additionally, these sources were instrumental:

The Conjurer Community YouTube channel

Many clips of Penn & Teller: Fool Us

In this post, I lean heavily on Penn and Teller—and in particular their account on This American Life—because they are not only tow of the greatest practitioners of magic, but also some of its most brilliant contemporary theorists. (If not otherwise specified, quotes are from the episode.)

I don’t know whether this timeline is typical, but another trick purportedly took them six years create.

Penn is talking here about how to connect with an audience in the context of public speaking, but he could just as easily be describing magic: Start with the effect you want to achieve, and then let all your methods flow naturally from that end goal.

Penn & Teller: Fool Us is perhaps at its most interesting when Penn and Teller guess a method that is both clever (i.e., I as a viewer would never have thought of it) and incorrect. In this episode, for example, they mistakenly suggest that in order to inexplicably pop a balloon, the magician contestant has used a small hidden pin; the magician decisively declares them wrong and claims his F U (“Fooled Us”) trophy.

Pike notes that while he’s certain he’s heard Penn and Teller describe the trick, he can’t find an online source. For a similar example of the “unreasonable amount of time” principle, see below (from this interview with Teller):

You will be fooled by a trick if it involves more time, money and practice than you (or any other sane onlooker) would be willing to invest. My partner, Penn, and I once produced 500 live cockroaches from a top hat on the desk of talk-show host David Letterman. To prepare this took weeks. We hired an entomologist who provided slow-moving, camera-friendly cockroaches (the kind from under your stove don’t hang around for close-ups) and taught us to pick the bugs up without screaming like preadolescent girls. Then we built a secret compartment out of foam-core (one of the few materials cockroaches can’t cling to) and worked out a devious routine for sneaking the compartment into the hat. More trouble than the trick was worth? To you, probably. But not to magicians.

David Berglas sadly passed away in 2023, but for the purposes of this post I’ve opted to describe his effect in the timeless present tense.

This piece, “Steering by the Method” is itself a demonstration of the method-first approach it promotes: Rather than planning top-down, I generated the post by taking the last letter of each sentence as the starting point for the next one.

The fact that we tend to appreciate performances more when we have some idea of how they’re done helps explain why experts often prefer different artists to laypeople (e.g., “he’s a writer’s writer” “she’s a comedian’s comedian.”) When you have just an inkling of how something is done, big flashy performances tend to be more impressive; when you know a lot, the flashy performance may look easy and technique or subtlety becomes more interesting.

Another visual analogy for the Berglas Effect comes to mind: The classic carnival game where you drop a disk down a peg board. Of course you can marginally increase the odds that the disk will end up on the left side of the board by dropping it from the leftmost slot—but there is a lot of randomness. Berglas, in this analogy, has even more influence over the disk than the average player: a magnet pulling on it at every juncture, tipping the odds in his favor. Even so, he often gets unlucky.

On this point, it’s worth meditating again on David Segal’s account of the Berglas Effect that was “off by one”: You could look at this as another failed “half-finished piece of magic”—or you could look at it, as Segal does, as quite impressive in its own right. The lesson here is that it’s often a mistake to think of success as binary. Getting an M.D. is not the only way to help people live healthier lives, and if you don’t make the NBA, you might still be able to play in the EuroLeague.

One intriguing corollary of this is that people who achieve success by being an outlier in one area will on average be worse than their peers on other factors. This leads to a phenomenon called Berkson’s Paradox, in which positive traits are wrongly believed to be anti-correlated. For example, if you are only looking at celebrities, you may infer that talented people tend to be less attractive, and vice versa: