Suppose you’re a talented but as-yet undiscovered musician who is trying to figure out how to maximize your chances of long-term success.

With this goal in mind, it might seem like the surest path for increasing your (already slim) odds of making it is to exploit what you do best: If you’re a decent guitarist, for example, then playing piano or singing a capella will just draw focus away from the feature of your music most likely to gain widespread recognition. A purely strategic approach (if not necessarily the most artistically fulfilling one) would seem to counsel, in this case, continuing to shred 🤘.

In fact, a recent study by Justin M. Berg suggests the opposite: A narrow artistic focus is not the best way to beat the odds—especially if your goal is repeated, consistent success in the music industry over many years. The author explains:

As creators begin their careers, focusing on products that reflect what is popular at the time may be the most likely and efficient path to initial success, but taking this path may undermine the likelihood of sustaining success. If the goal is sustained success, creators may need to resist the temptation to achieve initial success quickly or easily. Instead, they may position themselves for sustained success by investing their time into generating a variety of novel products early in their careers.

I’ll return to this study shortly and explain exactly what it found and looked at. For now, though, just note the broader phenomenon at play: Trying to achieve a goal as quickly and directly as possible does not necessarily produce the best outcome. This false assumption—that faster, more goal-directed action is always desirable—is one I’ll refer to in this post as “the Efficiency Trap.”

As I’ll argue, the Efficiency Trap has important implications not only for creative industries but also for how we think about productivity and difficult problems in general. Escaping this trap allows us to move about the world more freely and effectively.

What Is the Efficiency Trap?

A quick clarification: By “efficiency,” I generally mean here the perceived TIME and EFFORT it will take to reach a desired goal, NOT material resources or money (though perhaps there are implications for these domains as well!).

Consider, for example, this old favorite of the blogosphere about producing high-quality pots:

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality.

His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pound of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot—albeit a perfect one—to get an “A”.

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work—and learning from their mistakes—the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

In this example, you could make the case that the quality group is less “efficient” because their work rate (e.g., pots-per-hour) is lower; this is not how I’m using the term. Instead, I mean that if the goal is to make a high-quality pot, most people would likely aim directly for this target—rather than the less intuitive solution of quantity as a means to an end.

In other words, the Efficiency Trap here is the belief that the best way to make a perfect pot is, you know, striving straight for perfection.

This ceramics story is a parable—albeit one rooted in truth. (The original is apparently about photography.) I like it because it’s memorable; but it’s not exactly hard evidence for the phenomenon I’m describing.

Perhaps, though, you’ll have noticed the parallel to the aforementioned study about musical artists? Here, we have actual data showing that more variety in an artist’s portfolio (or, roughly, the “quantity” group) is in fact associated with greater long-term success!

Specifically, the study found that an artist’s success (as measured by songs in the top 10, 40, and 100) is predicted by their full portfolio of music at the time of their first hit. There are three variables Berg looked at in relation to this:

First, more variety in that early portfolio increases the likelihood of repeat hits.

Second, more novelty (relative to other artists) in that early portfolio increases the likelihood of repeat hits.1

Third, artists face pressure to continue making music that is related to their early portfolio (due to both internal learning and external expectations).

Or in graphic format:

Together, these results suggest that making a lot of different “pots” (i.e., variety) and making more unique “pots” (i.e., novelty) truly are the best strategies to increase the odds of long-term success (at least until you have your first platinum-selling megapot, so to speak, at which point people will enter your pottery shop with certain expectations about the kinds of pots you make).

But there’s a catch—one I alluded to earlier: While variety is an “unmitigated good” in a creative portfolio, novelty presents a “thorny tradeoff.” Berg describes:

[T]his study uncovers a tradeoff between initial and sustained success based on the novelty (versus typicality) in creators’ early portfolios…Typical portfolios in this dataset were more conducive to initial success, but reaching initial success with a novel portfolio was more conducive to sustained success…Variety may help artists compensate for this tradeoff to some extent, as variety in this study predicted both initial and sustained success, but variety did not eliminate the tradeoff…In short, creativity is a high-risk, high-reward investment that could make or break an artist’s career. Building a typical portfolio is a safer bet in terms of having at least some success, but the upside is limited as this success may be short-lived.

In this light, I suppose I’m arguing here in favor of taking the riskier bet—that is pursuing more original creative endeavors, even if those projects take longer to gain traction.

I’d also argue, re: variety, that while perhaps there is not a true economic tradeoff (it doesn’t literally cost more to make more varied songs), the perceived and experienced effort to pull off a diverse portfolio are surely higher. This counts as an Efficiency Trap in my view because it’s a less obvious/direct strategy than making lots of similar songs that play to one’s strengths.

What about outside the arts? In a recent blog post, Eric Gilliam explored a similar set of issues in the context of academia. Because I haven’t actually read the paper thought his summary was excellent, I’m just going to quote it at length here:

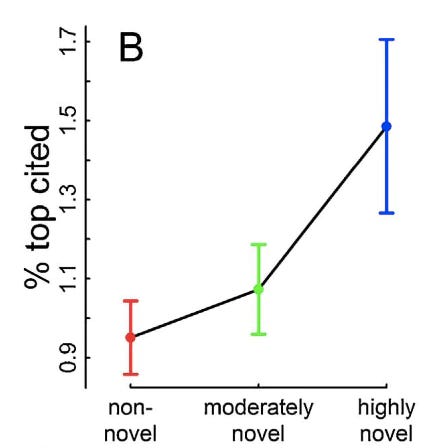

Wang et al. look at the novelty of scientific papers and their likelihood of becoming a top 1% cited paper written in their field. And, in an exciting turn of events, highly novel papers are far more likely to become blockbuster papers, rewarding the researchers for their risk!

But there’s a problem. It takes years for those citations to accumulate and for your paper to become appreciated. Like, enough years that your tenure vote may come and go without the paper being appreciated. At the 3 year mark, you may still have about the same number of citations as the completely non-novel research on average, possibly less.

In this instance, Gilliam’s point is actually that the incentives in academia are really screwed up. (He goes on to share a third graph showing that the blockbuster papers are more likely to be cited in a foreign field than the author’s home field). My inclusion of it is simply to demonstrate the pattern I’ve been talking about: If you’re tackling bigger, weirder, more interesting problems, it just takes longer for your solutions to stick.

I do want to be careful here about conflating “quantity” and “variety” and “novelty”—which are, of course, all different concepts. But they are concepts with roots in a common attitude about creativity and productivity that is at the crux of the Efficiency Trap.

The rest of this post is devoted to giving voice to that attitude.

What Isn’t the Efficiency Trap?

Let me take a brief detour to distance my claim from some others that bear resemblance to it.

I’m not saying that efficiency is in and of itself bad. Efficiency, after all, simply means succeeding with minimal expenditure of resources—working well and quickly at the same time. Who could possibly be against that?

I’m also not saying that inefficiency is in and of itself good. Inefficiency that results from distraction, ineptitude, or overregulation is obviously undesirable—especially in systems whose very purpose is to allocate resources or information. (Think large government bureaucracies.) As a general rule, bigger organizations suffer more from a lack of efficiency than an excess of it.

Rather, I’m saying that while efficiency itself, in the abstract, is good, an efficiency MINDSET in practice often stifles agency and runs counter to the highest forms of human problem-solving.

In other words, inefficiency is a necessary (albeit insufficient) evil that reflects a reality of the human condition: For most people, most of the time, it’s just not possible to simultaneously produce a high quality and high quantity of work. People aren't successful because they're inefficient any more than Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates are successful because they dropped out of Harvard. Rather, they’re successful because of the benefits that inefficiency enables: discovery, deliberation, etc. (More in the next section!) And in fact, we already have words for inefficiency absent these benefits: good old-fashioned procrastination or avoidance.

To be fair, I’d also concede that an efficiency mindset can promote its own kind of creative energy. Efficiency biases us toward action; when we have a looming deadline or a packed schedule, we don’t have the luxury of deliberation and agonizing over our choices: We go with our gut—with the first best option. This kind of mental state can be exciting and generative because it makes us less inhibited, often revealing implicit knowledge and resourcefulness.

But when we slip too reflexively into action mode, or become self-flagellatingly obsessed with squeezing productivity out of every single minute of our days, we ultimately disempower ourselves—and fail to capitalize on some of the natural capacities of the human mind.

The question now becomes why/how efficiency traps us in the first place—and what can be done to break free.

Escaping the Efficiency Trap

If there is one thing I hope people take away from this post, it is simply that it’s possible for inefficiency to be good. Not just that a lack of productivity is something about which you should be “kind” or “forgiving” to yourself—but that it’s actively beneficial to slow down.

There are seven(ish) reasons for strategic inefficiency that come to mind, some of them explanations I’ve already gestured towards—others yet to be discussed:

Efficiency robs us of the chance for epiphanic insight. Our best and wildest ideas (colloquially, “shower thoughts”) are often born in are often born in a relaxed associative state when we aren’t actively looking for them. If the little voice in your head is demanding a fix NOW, you’ll likely be able to come up with a sufficient solution—but what are the chances it’s a brilliant solution? (And how would you even know, if you’re not pressure-testing it and comparing it to other options?)

Efficiency robs us of the ability to make careful, considered decisions. Although an abundance of choice can lead to analysis paralysis, working through such struggles in a systematic—albeit slower—manner surely does produce better outcomes: We’re smarter when we have time to check our answers, anticipate pitfalls, and look at issues from different angles.

Efficiency robs us of the opportunity to gather more data. This is perhaps a subcategory of the point above—and one I touched on in a I touched on in a previous post (i.e., “Break 1”): Often, during the gap between the initial inception of an idea and its actual creation/implementation, unexpected resources and collaborators will emerge simply because we are primed to look out for them. This prep time makes space for influences that might otherwise not find their way in—ultimately setting us up for more effective action.

Efficiency generally buys you more stuff to do—not a sense of accomplishment. It’s easy to fall for the illusion that if you get through your to-do list faster, you’ll have more time to relax and live your life. While this is may be true in some instances, sadly the more common pattern seems to be that extra time is simply filled with new goals and even more packed schedules. In this case, efficiency traps us by making ever-steeper demands until either our psyche or work product suffers.2

“Inefficient” processes are often less wasteful than they appear. In the study on musical artists cited earlier, one reason more varied portfolios enabled greater success is because they gave artists more creative directions to go in (e.g., if music trends changed). Similarly, skills, knowledge, and personal connections that appear to serve no short-term purpose can prove useful down the road in totally serendipitous ways; while we can’t predict these uses, a certain looseness in the pursuit of our goals can help them happen.

Some people/problems will self-resolve or become less relevant. Deadlines get pushed back; inexplicable injuries heal on their own; email requests get followed up with a Never mind—found it! In other words, resisting the urge to fix issues the moment they arise can save us unnecessary time and energy. (Of course, most problems are decidedly not like this: Those dishes aren’t going to do themselves.)

Sometimes a better offer will come along later. Again, perhaps a subvariant of the one above. In this particular instance, it’s not a problem that tempts an immediate response but an opportunity you’re less than jazzed about. Just because it’s the first or only job you’re looking at doesn’t mean a better one won’t come along tomorrow—one you’ll have to turn down if you’re too trigger-happy with your yeses.

Looking at this list, it strikes me that there’s not just one phenomenon at play here but multiple efficiency trapS: different reasons why, in different contexts, there might be a benefit to a slower or less direct approach.

Once we accept this, we can observe the kinds of activities that suggest or demand greater efficiency: impending deadlines; mindless implementation of solved problems; situations where the consequences of inaction are worse than the consequences of enacting a suboptimal solution (e.g., the emergency room).

And we can observe the kinds of activities that suggest or demand less efficiency: research; brainstorming; exploration; coalition building; situations where the consequences of getting it wrong are worse than the consequences of inaction (e.g., clinical trials for a never-before-used drug).

Then, once we’ve put activities into the “efficient” or “inefficient” bucket, we can set about making systems to encourage this reality.

On the individual level, this might simply be a kind of internal psychological reward—for example, deciding to keep track of the time you spent writing/working (incentive for inefficiency) rather than the number of words you wrote/widgets you made (incentive for efficiency).

On the organizational level, it means greater clarity about when efficiency is and isn’t expected. W. L. Gore, of Gore-tex fame, provides a strong positive example (as described here):

Often heralded as one of the world’s most innovative companies, W. L. Gore embraces rapid experimentation. To begin with, the company has “dabble time,” which is an expectation that approximately 10 percent of employees’ time will go toward new ideas or initiatives. In addition, the company is more than willing to make long-term investments in ideas that take time to develop. The organization’s status as a privately held company, in which employees are given shares as part of their compensation, shields it from the pressure of achieving quarterly results typical at publicly traded companies. For these reasons, it is common for employees at W. L. Gore to tinker with ideas that eventually become new products.

One example of rapid experimentation is the development of W. L. Gore’s line of Elixir guitar strings. One of the company’s engineers, Dave Myers, worked in a Gore medical devices plant developing new types of heart implants. As part of his dabble time, Myers was trying to improve his mountain bike by coating his gear cables with a layer of plastic, hoping to make the gears shift more smoothly. His tinkering was successful, giving rise to Gore’s line of Ride-On bike cables. After a series of other experiments, Myers thought of using a similar coating of plastic on guitar strings to improve their durability and feel. Not being a guitarist himself, Myers sought the help of Chuck Hebestreit—a colleague who played guitar. The duo experimented with the idea without success and without management awareness of their efforts until John Spencer—a colleague who had successfully brought a best-selling line of dental floss to the market—joined the effort. Shortly thereafter, the team had a viable product. They sought official sponsorship from the company to take their guitar strings to market. The team had great success: Elixir is a highly regarded brand of guitar strings and was the market leader in sales in 2004, capturing 35 percent of market share.

The notion of “dabble time” would sound pretty radical at most companies—yet in absolute terms, it seems like quite a small price to pay (“approximately 10 percent of employees’ time”) for long-term innovation and (presumably) higher employee satisfaction.

It also occurs to me that incentives for greater or less efficiency are often baked into compensation structures, with salaried positions encouraging employees to work as quickly as possible (or, alternatively, to cut corners) and hourly ones encouraging employees to work as inefficiently as possible (or, alternatively, to seek out more problems to solve). Of course if the only thing you knew about an employee was how efficient they are, you’d probably want someone faster rather than slower—but it’s not clear to me that one system is definitively better for all situations.

(Related: Why is it that more senior/strategic positions tend not to be hourly? Aren’t these exactly the kinds of jobs where you’d want to give people an incentive to spend more time? Then again, I guess anyone in a company’s C-suite probably already faces plenty of social pressure to work long hours.)

If there is a fault in the logic of efficiency, it lies in thinking that people—even a single individual—should be working the same way all the time. It’s easy to be a hard-driving manager (of others or yourself) who just wants more and faster. It’s much more difficult to be an effective manager who makes the ever-shifting value judgments of when to prioritize speed vs. quality.

Inefficiency for Its Own Sake?

Up to now, I’ve been insinuating what could be called “master’s-tools logic”—i.e., that inefficiency is, really, more efficient in the long-run because it promotes creativity, agency, etc. Inefficiency beats efficiency at its own game.

But it’s also true that inefficiency sometimes really is just, well, slower—in the short- and long-run. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

When is inefficiency good in its own right—not just as a means to an end? First, consider that sometimes it is the very spending of time on an activity that confers value on it. There are some special projects and situations that prompt us to think, I don’t care how long this takes; I want to sit with this for a while. (Imagine, for example, the indignity of trying to rush through a eulogy or a wedding ceremony as quickly as possible.)

On this point, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi—popularizar of the concept of “Flow”—relates this climber’s account of what it feels like to lose track of time doing something you love:

The mystique of rock climbing is climbing; you get to the top of a rock glad it’s over but really wish it would go on forever. The justification of climbing is climbing, like the justification of poetry is writing; you don’t conquer anything except things in yourself…. The act of writing justifies poetry. Climbing is the same: recognizing that you are a flow. The purpose of the flow is to keep on flowing, not looking for a peak or utopia but staying in the flow. It is not a moving up but a continuous flowing; you move up to keep the flow going. There is no possible reason for climbing except the climbing itself; it is a self-communication.

Clearly there is a value here—one I hope all of us have experienced—that “efficiency” fails to capture. It’s about the process, not the product.

Second, what looks like a lack of economy in one light is, in another, the very quality that imbues creative efforts with force and character. Consider, for example, this passage from Bird by Bird with an eye not just for what Lamott says but how she says it:

I visited a memorial garden at the radiation clinic where [a deceased friend] had been treated, and discovered that someone had planted a yew tree there in her honor. The yew was bigger than me and fuzzy, like an Edward Koren character. It looked like it might suddenly come over and hug me. Near the yew were tall flowering bushes—some kind of poppy, perhaps. But almost all of the petals had fallen off, so mostly I just saw a thousand tangled stems growing skyward. Then I realized that the stems were actually connected, and that they bore seeds that would flower again in the spring.

That’s how real life works, in our daily lives as well as in the convalescent home and even at the deathbed…You can see the underlying essence only when you strip away the busyness, and then some surprising connections appear. [link mine]

In fact, I don’t think Lamott’s point here is so different from #5 in my little listicle above (“inefficient” processes are often less wasteful than they appear); yet her words are richer and more memorable despite—or, really, because—there are more of them. What runs the risk of becoming a cliche or aphorism in other contexts is grounded here in the particulars of her experience.

Similarly, there are questions we face right now, as individuals and a society, that it is more important to answer effectively than to answer efficiently. If history is any guide, the answers to these questions are, in all likelihood, just variations on ones that have been offered before—solutions from other fraught times and places, invented by smarter people than you or me.

But it is your experience—your past mistakes, your pet examples and analogies, your friends and family and mentors—that will make these answers singularly yours. Take as much time as you need 🙂.

TL;DR

An overemphasis on efficiency is detrimental to long-term success and human flourishing: Permission to take one’s time empowers better choices, more creative solutions, and ultimately, the realization of greater individual potential.

Thanks to Charlie for edits.

One thing I found slightly confusing: It seems like the artists who are creating more varied music would also inevitably be creating more novel music? Berg seems confident these are separate constructs, saying, “In practice, novelty and variety may be positively correlated, but the two dimensions are conceptually distinct and should have plenty of independent variance.” Still it’s hard for me to imagine the sound of an artist who is high in variety and low in novelty. (Would that be, e.g., if they only made bubblegum pop, but the songs had a lot of diversity in their melodies, danceability, etc.? I’m not sure.)

In keeping with point #3, this is an idea a friend shared with me while I was in the midst of working on this very post; the source is an excerpt from the book Four Thousand Weeks—and even uses the exact same terminology (!): “The general principle in operation is one you might call ‘the efficiency trap’. Rendering yourself more efficient—either by implementing various productivity techniques or by driving yourself harder—won’t generally result in the feeling of having ‘enough time,’ because, all else being equal, the demands will increase to offset any benefits. Far from getting things done, you’ll be creating new things to do.”