One strange feature of our silly little brains: A simple reframe of a goal can make the exact same individual vastly more successful at completing the exact same task.

Kurt Vonnegut, for example, famously advised writing “to please just one person.” Would-be meditators are told to imagine their breaths as colors, lotus petals, or rays of light. Software engineers identify bugs in their code by “rubber ducking”—explaining the issue in detail to an inanimate object until they locate the source of the problem. None of these reframes change anything about a person’s underlying knowledge or abilities; they simply unlock a more effective use of existing mental resources by which to meet the challenge.

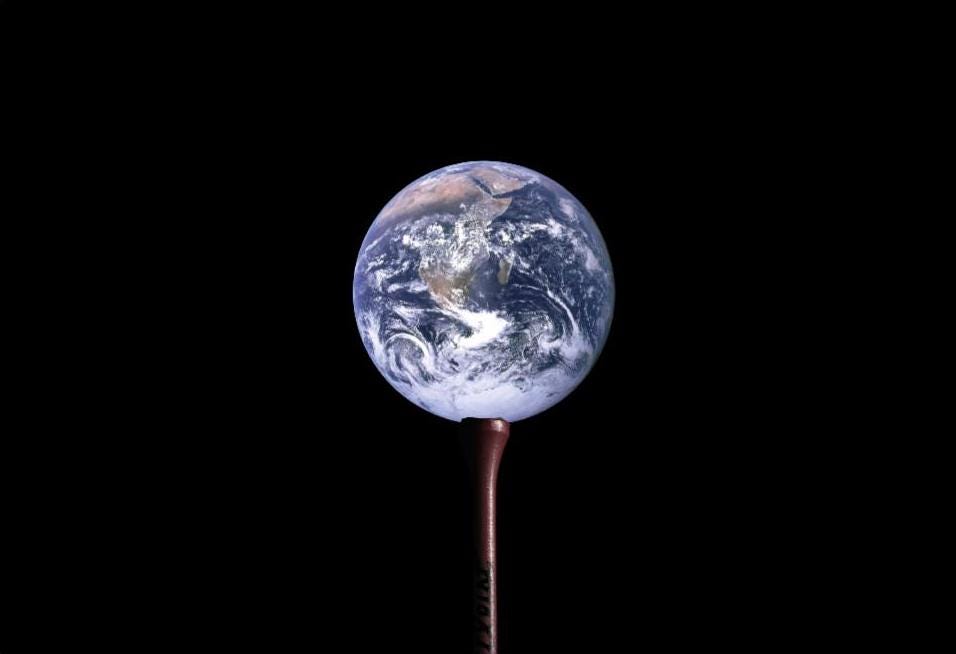

My own humble contribution to the tradition of human prompt engineering—admittedly a more general, process-oriented one than Étienne’s: Instead of treating a task as a to-do item in its own right, try thinking of it as simply “teeing up” greater success tomorrow. (And watch as you instantly become less stressed and more productive!)

Two Types of Teeing

In fact, there are a couple subspecies of teeing up that should be differentiated:

1. Freeing up Time and Bandwidth

This is teeing in its most basic conception: an effort to reduce future demands on our mental resources. It might mean, for example, tackling a small, easy task when you’re not in the mood to take on the big stuff. Sure, emptying the trash doesn’t directly contribute to that website you’re building or that piano concerto you’re composing—but at least it’s one less thing to pull you away from the keyboard.

In making these bids to free up time, however, it’s important to remember that you can’t really get out from under your to-do list in the long run. (More on that in a moment.) The goal is not to fully clear the decks, but, rather, to simply make them a little clearer—and, later, be grateful they’re not worse.

2. Preparation for a Bigger Project

In one light, teeing up tomorrow, looks like a cheap trick to save us from our own passivity. In another, though, it’s actually an appropriate response to a legitimately thorny stuckpoint: For projects of sufficient size and scope, we usually can’t really begin to make headway until after some floundering around; and we don’t always have the time or headspace to flounder. Sensing, then, that we won’t really be able to make headway today, we (justifiably) opt to wait until we’re ready and able.

The flaw in this approach is that we may never be ready and able without a bit of activation energy. In truth, our intuition—i.e., that we won’t really be able to make headway today—is correct: Teeing up may result in little tangible progress. What it does do, though, is help create better psychological conditions for tangible progress. Often, it entails “work” that seems redundant or inefficient: rereading instructions; summarizing what we already know; reading or listening to an expert talk about vaguely related experience. This kind of labor might seem wasteful, but it can dramatically reduce the friction we feel before the heavy lifting.

Of course, once you get started on a project (i.e., under the pretense of “teeing up tomorrow”), you’ll often find that you have a better sense of what to do than you realized. This is a great outcome!

In other instances, you might find that when tomorrow rolls around, your attempted teeing didn’t work: You’re still not ready to dig in. In this case, simply rinse and repeat: Tee up the next day—and, if necessary, the one after that, and the one after that—and eventually you’ll likely realize that by successively “preparing” to work, you’ve actually accomplished quite a bit.

(E.g., in the context of writing—though this certainly generalizes across domains: Oh, I’ll just list the possible subject of each paragraph, you might say on day 1; then Well, maybe I’ll drop in a quote or a link I saw that seems relevant; then Ok, here’s how I might summarize the main point of said quote or link; and suddenly you look up and realize you have a third of an essay written—all without ever doing anything that resembles hard labor.)

Why It Works

The basic mechanism behind teeing up tomorrow is, I think, recasting our productivity debt as a productivity credit.

That is, instead of psychologically punishing ourselves any time we fail to meet a goal, we start with the null hypothesis that we are a lazy piece of shit who will never accomplish anything. This way, getting something done, however small, becomes a victory! I know: It sounds like a painfully obvious self-deception—one that shouldn’t work, at least not in the long run. And maybe it won’t work for you, I can’t say. All I know is that for me, it’s been remarkably effective in combating stress and avoidance around all kinds of projects.

Consider, too, that the default assumption of underaccomplishment is actually truer, in a cosmic sense, than the belief that you’ll finish what you want to. This is because a) there are literally infinite things you could be doing with your time, and b) [SPOILER] you are eventually going to die. So far from being a clever bit of spin, teeing up tomorrow reflects a core fact of our finite lives: There will always be more to do than is humanly possible.1

Accepting the sad and unavoidable reality of our finitude, the question then becomes why and how we should do anything at all. One answer, of course, gestures vaguely toward the strength and nobility of the human spirit—rage, rage against the dying of the light, etc.: Even if I can’t accomplish everything I want, we might think, I’m still going to get done as much as I can, in the time I’ve got left!

If you’re someone for whom this mindset is conducive to productivity, then power to you! Personally, I’ve always found it to be a lot of pressure. My preferred approach, per this post, is to simply say to myself: Even if I can’t accomplish everything I want, I can still make the process a bit less miserable, when I inevitably get suckered into trying anyway.

So look, I don’t know who needs to hear this, but…Let yourself off the hook for whatever you thought you’d get done today. It’s already 6:00 p.m, for Christ’s sake—it’s not happening!

Then, if you want, you big dumb baby, you can do something right now that might make the future that much more possible to face.

TL;DR

Instead of agonizing over what you have to accomplish today, simply aim to take pressure off the “real work” you’ll complete tomorrow.

This insight serves as the foundation of Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals.

In our culture, maybe we put too much emphasis on getting stuff done rather than just "being". Accomplishment feels good. But we should also make time to feel happy "now" (a little Buddhist thinking on this Thanksgiving Day!)