Updated (read: shorter) version here.

There’s a kind of takedown you see on social media that takes this general form:

In scenario A, my political opponent cites [VALUE]. In scenario B, they demonstrate [OPPOSITE VALUE]. My opponent is a hypocrite!

And lest anyone accuse me of cherry-picking only right-wing hypocrisies, here’s a couple anti-woke examples for ya…

These Tweets all have the same “gotcha” quality that—depending on whether you agree or disagree—makes them either delicious or infuriating.

But dig a little deeper, and the schtick starts to get old pretty quickly: It’s a bit of a rhetorical parlor trick.

Consider, for example, the first Tweet above, and how a conservative might frame the same two issues. (The “pro-choice” LIBS are the same ones that declare vaccine MANDATES for our CHILDREN.) Or—if you prefer to take it from the opposite direction—note the tendency, per the last Tweet, to see violent extremism as a sin of just one’s enemies: Marjorie Taylor Greene has it exactly backwards—it’s Fox News and the Jan 6th insurrectionists who are a threat to our democracy! (Never mind that available data show violence is a much bigger problem on the right; I’ll return to both-sides-ism at the end.)

The point here isn’t that everyone here is equally bad; it’s that structurally speaking there is a symmetry to the so-called hypocrisy.1 And if you would condemn both your opponent’s positions, then this charge of inconsistency can just as easily be turned back on you.

Of course, if your goal is simply to express solidarity, to entertain, or to play offense, there’s no problem here.

If your goal is to persuade or debunk, though, I think there’s an important principle here: The mere appearance of inconsistency doesn’t actually tell us much.

Ok, So Consistency Doesn’t Matter?

Consistency matters. I just think there’s a limit to its usefulness in moral/political debates.

On the merits, for example, I personally feel that the “pro-life” position is justified for vaccines and not at all justified for abortion. But that’s not because I see an intolerable contradiction in the conservative stance, or think the table above is a misrepresentation of my own; it’s because I see, in vaccination and abortion rights, two very different issues with very different histories and sets of tradeoffs. It is these very particular contexts that I invoke when I favor “choice” in one case and “life” in the other.

It’s worth noting that there’s another way to square the circle here. An alternative response to symmetrical hypocrisy would be to decide that consistency really does matter, and to demand it of both oneself and one’s opponents. Presumably this would require developing/subscribing to a moral framework that is sufficiently well-defined as to inform moral reasoning in all situations; but even if such frameworks actually exist (I’m skeptical), questions will surely arise when we actually attempt to apply them. (E.g., If the goal is to maximize “utility,” is it right to break the rules for short-term good—or will this good be undone by the long-term undermining of rules in general?)

Furthermore, an expectation of perfect internal consistency can invite rationalizations and moving of goalposts. Let’s look at another made-up example here, and the various ways people might frame it:

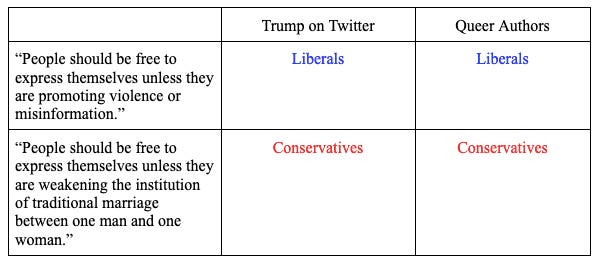

The same people who whine about Trump being kicked off Twitter are the ones trying to ban books by queer authors. #Hypocrisy!

Suppose liberals want to be internally consistent, but don’t want to concede that Trump should be allowed on Twitter. In fact, they reason, the real value they support is “People should be free to express themselves unless they are promoting violence or misinformation.” Then liberals appear principled and conservatives appear hypocritical.

Smart! But suppose conservatives counter with their own revised value: “People should be free to express themselves unless they are weakening the institution of traditional marriage between one man and one woman.” Now we have a new equilibrium, in which both sides are internally consistent yet remain in disagreement with one another:

Again, to be clear, I think the conservative standard here is contrived and ridiculous—but it’s not like the liberals sound quite so parsimonious now either, nor are the rules easy to define. (What counts as “violence” and “misinformation”? Do excessive retweets warrant deplatforming, or does the offender have to be the original author?)

More importantly, note that once we allow for these kinds of qualifiers, they may give rise to any number of convoluted standards that make one side appear (in)consistent. People can refine their values as much as they want until they match the moral situation at hand—with no final arbiter of which refinements are fair game. So in practice, I think demanding “consistency” is often a recipe for mental gymnastics and entrenchment of beliefs.

To be fair, sometimes the desire for consistency really does prompt a widespread updating of norms. In the aftermath of #MeToo, for example, there was a marked reassessment of Bill Clinton’s behavior toward Monica Lewinsky—as expertly detailed in season two of Slow Burn. This reconsideration was surely motivated in part by a desire to hold bad actors to the same standard regardless of political affiliation. (Also, of course, enough time had passed that Clinton’s supporters could admit mistakes without losing much face.) At their best, social movements increase the salience of some values over others—and there are clear examples of that working to great effect.

Finally, it’s important to note that not all hypocrisies are symmetrical. In some (maybe most?) cases, it’s really only one side that is engaging in self-contradiction.

If, for example, you believe that Trump should be allowed back on Twitter and that queer authors should continue to be published (i.e., you’re a libertarian/free speech absolutist), then it seems perfectly legitimate to appeal to open discourse as a shared value:

In the same vein, do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do hypocrisies are usually pretty clear-cut: It’s one thing to appeal to Value A in one situation and Value B in another because you believe the contexts are truly different; it’s another when Value A is “life is sacred and begins at conception” and Value B is “unless I don’t want people to find out I was having affair and/or am a registered sex offender.”

Crucially, though, there’s a temptation to assume that all hypocrisy is asymmetrical, or to shoehorn complex issues into this paradigm. This is, at the very least, a little silly—and at the worst actively counterproductive.

What’s the Solution?

First, let me just say that I totally get why people like to point out hypocrisy. It feels good to be right. It’s fun!

I just hope that in addition to a sense of smugness, Tweets like the ones above prompt a brief moment of introspection: Are we ourselves being consistent? If not, what are the (good, thoughtful) reasons why the two situations are disanalogous? This questioning—and reaffirmation—of our beliefs should make them clearer and sharper.

Second, remember that if you find yourself in a symmetrical hypocrisy, going on attack is unlikely to persuade someone who doesn’t already accept your underlying assumptions. If we don’t accept someone’s assumptions, their charges usually strike us as annoying and uncharitable—a deliberate flattening of the moral landscape, or omission of other important considerations. (This at least is how I feel when I read the Tweets I disagree with above.)

To drive this home: I’m not (just) talking about confirmation bias, in which people reject any new evidence they don’t like. In fact, I do think persuasion is possible. (Some of my best friends are persuadable!) But in symmetrical hypocrisies—in which both parties’ internal contradictions are mirror images of one another—it seems particularly futile to point out said contradiction as a persuasion tactic: Why would you conclude that you are in the wrong when you can just as easily conclude that I am?

I would argue that the only time a good faith charge of hypocrisy really makes sense is if you actually agree with your opponent on one of their positions. This is not just because finding common ground is more persuasive (although it is), but because once a contradiction appears, it can theoretically be resolved in either direction; when you can point to agreement, then, you prevent the wrong conclusion being drawn. (E.g., after complaining about—then engaging in—gerrymandering some politicians might concede, “You’re right. Everyone should be allowed to create fundamentally undemocratic electoral maps!”)

Third, remember that, absent other key information, symmetrical hypocrisy tells us nothing about who is actually right. If we imagine, for example, that Alice supports the freedom to murder and opposes the freedom to fart in elevators, while Bob is the opposite—anti-murder and pro-farting-in-elevators—well, both Alice and Bob are “hypocrites,” but clearly one of these “freedoms” is way more problematic than the other. (People who fart in elevators should burn in HELL.)

The truth is, we’re all moral chimeras, or chameleons—or, if you must, snakes. This doesn’t absolve us of responsibility for coming up with any consistent standards for behavior; rather, it means that it’s normal, advisable even, to sit with contradiction in a world that is itself complicated and constantly evolving—when the values we hold dear so often come in conflict with one another.

Or, if you’d rather just point out others’ inconsistency and get defensive/dismissive whenever people point out your own, that’s cool, too! Just know that it makes you a bit of a…you know…

TL;DR

When someone holds two contradictory beliefs—both of which you disagree with—it can also be said that you hold two contradictory beliefs.

Therefore, I argue in favor of:

Introspecting about our own values when we notice this happening.

Engaging hypocrites in debate only when we agree with one of their positions.

Recognizing that inconsistency is not inherently sinful.

Thanks to Ari for edits.

Arguably, “contradiction,” “inconsistency,” or “cognitive dissonance” might be closer to the phenomenon I’m describing. But hypocrisy carries a sense of moral outrage that feels important to this discussion.