Gilead, it turns out, is not just one of the more common mispronunciations of my name;1 it is also the title of an excellent novel by Marilynne Robinson.

Narrated as single long letter from an aging pastor to his young son, Gilead accumulates a quiet power as it goes: through depictions of faith and mortality, water and fire, painful estrangement and tender reconciliation. It is, above all, a testament to a slow, simple way of life that has ceased to hold much sway in the public eye.

I first read Gilead several years ago and recently returned to it for a second time. Until this read, I’d never given much thought to its cover. Though we’re told not to judge on this basis, most marketing departments would beg to differ; I could only assume there was considerable thought invested in the washed-out image I held in my hands:

What exactly was I looking at? Certainly, the faded blues and greens on the side of an old building speak to the forgotten world of the Gilead, Iowa. The window is an almost literal manifestation of the bigger project of the book: a view into that way of life. And then, suddenly, it hit me.

I was looking at a cross.

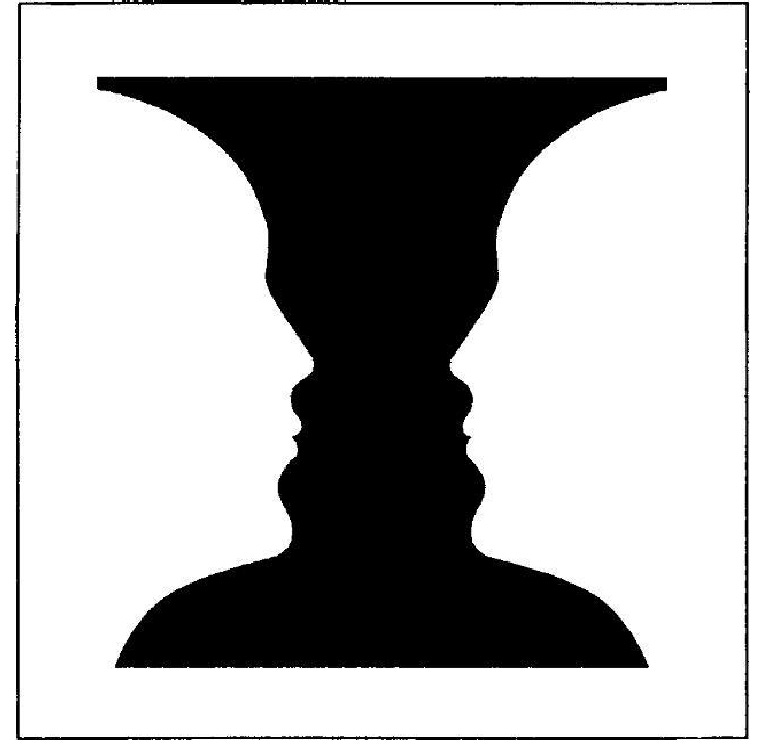

This discovery brought with it the thrill of finding an Easter egg in a work of art. But as I continued to stare at the image, it struck me that it wasn’t really an Easter egg in the traditional sense.2 After all, the cross wasn’t hidden; there was no secret puzzle to solve in the text. It had been there all along, sitting in the negative space of the window, and I just needed to change my perspective to take it in. In this sense, the experience of “discovering” the cross was more like the classic Rubin’s vase illusion, when your vision suddenly locks onto the two faces:

Rubin’s vase and (to a lesser extent) the cover of Gilead are examples of a phenomenon called multistable perception.3 These are images in which a single stimulus is consistent with two or more interpretations; each interpretation is “stable” in the sense that it effectively crowds out the other. If you weren’t aware that the image was multistable, you wouldn’t even notice the alternative.

When I returned to the novel now, it was with the concept of multistable perception in the back of my mind; this had the rewarding effect of unlocking the text for me, giving it new meaning. Particularly striking were the moments where John Ames, the pastor-narrator of the story, grapples with challenge to his faith—for example:

I have a certain amount of experience with skepticism and the conversation it generates, and there is an inevitable futility in it. It is even destructive. Young people from my own flock have come…And they want me to defend religion, and they want me to give them “proofs.” I just won’t do it. It only confirms them in their skepticism. Because nothing true can be said about God from a posture of defense.

And shortly after:

In the matter of belief, I have always found that defenses have the same irrelevance about them as the criticisms they are meant to answer. I think the attempt to defend belief can unsettle it, in fact, because there is always an inadequacy in argument about ultimate things.

In the first of these passages, Ames seems to acknowledge, in his own way, that his religious worldview has no rational response to criticism: “nothing true can be said about God from a posture of defense.”

But look closer, in the second passage, and you’ll see that he isn’t really conceding this at all. It’s not that his faith has no counterarguments but that, in Ames’s eyes, there is no basis for argument in the first place; faith is indefensible not because it is false but because it lies orthogonal to or outside of the physical reality to which we have access: the crucifix between the panes. Or as he puts it earlier in the novel: “My failing the truth could have no bearing at all on the Truth itself, which could never conceivably be in any sense dependent on me or on anyone.”

In other words, it’s as if Ames has witnessed the wonder of two faces, and skeptics keep demanding he rebut the vase.

To be clear, scripture does make many falsifiable claims. The universe was not created in a week, oceans don’t split down the middle, and a jolly man doesn’t come down your chimney each December to deliver presents. To accept these claims literally is to put oneself in what Ames calls “a false position”—a kind of fundamentalist blindness that is irreconcilable with basic reason or observation.

But for a wider segment of spiritual and quasi-spiritual people, religiosity is a normative and subjective stance rather than descriptive one; for these individuals, tradition offers guidance on how to treat the stranger, how to grieve and pray, how to cultivate a certain kind of consciousness. Such mental states are powerfully persuasive to the individuals who draw on them, yet they can offer no objective evidence for external parties. (Ames again: “Creating proofs from experience of any sort is like building a ladder to the moon. It seems that it should be possible, until you stop to consider the nature of the problem.”)

In the end, Robinson does make a powerful case for spirituality in Gilead—but at its strongest, this case is made aslant, in juxtaposition with other events. We feel a divine presence indirectly, in the way water catches the light as it falls from a branch:

There was a young couple strolling along half a block ahead of me. The sun had come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn’t. It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don’t know why I thought of them now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash.

Or in moments of special attention to celestial bodies:

Every prayer seemed long to me at that age, and I was truly bone tired. I tried to keep my eyes closed, but after a while I had to look around a little. And this is something I remember very well. At first I thought I saw the sun setting in the east; I knew where east was, because the sun was just over the horizon when we got there that morning. Then I realized that what I saw was a full moon rising just as the sun was going down. Each of them was standing on its edge, with the most wonderful light between them. It seemed as if you could touch it, as if there were palpable currents of light passing back and forth, or as if there were great taut skeins of light suspended between them. I wanted my father to see it, but I knew I’d have to startle him out of his prayer, and I wanted to do it the best way, so I took his hand and kissed it. And then I said, “Look at the moon.”

Or in the solitary beauty of walking at night:

I walked up to the church in the dark, as I said. There was a very bright moon. It’s strange how you never quite get used to the world at night. I have seen moonlight strong enough to cast shadows any number of times. And the wind is the same wind, rustling the same leaves, night or day…I remember walking out into the dark and feeling as if the dark were a great, cool sea and the houses and the sheds and the woods were all adrift in it, just about to ease off their moorings. I always felt like an intruder then, and I still do, as if the darkness had a claim on everything, one I violated just by stepping out my door.

These passages do not attempt to rebut the vase. The vase, it’s fair to say, is unrebuttable—it cannot be denied once you’ve seen it.

Instead, they invite us to enter a heightened, equally stable state of perception: to gaze back at the face that, illusion or not, is surely a sacred offering.

Other standouts include Jeelad, Eli, Gilo, Gilard, and Goliath.

More like a Good Friday egg, amirite guys?

See also: Necker cube, rabbit-duck illusion.