“Style,” writes literary critic Parul Sehgal, “is 90 percent punctuation.”

Granting that 90 might be a high (if totally symbolic) estimate, I’m inclined to agree that punctuation is a ~big deal~. And all the more so because it’s often not something we think about as we read.

Consider, for example, the two versions of the paragraph below—which I’ve composed for demonstration purposes out of the exact same 100ish words:

It was a warm, sunny morning. I could hear the squirrels chattering outside. And I felt a productive day was almost certain: my first in a while! It took me fifteen minutes some days just to get out of bed—yet to my pleasant surprise, I sprang off the mattress today and was out the door in ten, maybe twelve, minutes. At work, I hit my daily quota of widgets around noon. During my lunch break, I therefore decided to buy myself this: double-fudge chocolatey-chunk ice cream! A single sundae never hurt anybody, right?

It was a warm, sunny morning (I could hear the squirrels chattering outside), and, I felt, a productive day was (almost) certain…my first in a while…It took me fifteen minutes, some days, just to get out of bed. Yet—to my (pleasant) surprise—I sprang off the mattress today and was out the door in ten (maybe twelve?) minutes. At work, I hit my daily quota of widgets around noon; during my lunch break, I therefore decided to buy myself this double-fudge chocolatey-chunk ice cream…a single sundae…Never hurt anybody—right…?1

I’ve made some pretty extreme choices here (surely no one in their right mind would use that many ellipses…)—but the point, I hope, is clear: Punctuation drastically changes the way we experience a writer’s attitude toward described events. Where narrator 1 is brimming with earnest confidence and industriousness, narrator 2 sounds, to my ear, nervous and self-undermining. The squirrels, so chipper and friendly in the first version, are suddenly a bit grating—the sundae a sad indulgence instead of a well-earned treat.

In this vein, I’m interested today in exploring how these kinds of punctuation choices manifest in different writers’ work—and why you should give a shit.

Let’s Eat Shoot and Leave Grandma: A Refresher

Perhaps you’ve encountered some didactic little joke about the importance of commas—phrases like “Let’s eat Grandma”; or “A panda walks into a bar—then eats, shoots, and leaves.”

(For my grammarians out there: the word “Grandma” is in the objective case, when a comma would put it in the vocative case—i.e., the difference between speaking to Grandma rather than about Grandma. In the panda example, the second comma turns “shoots” and “leaves” into verbs when they should be nouns.)

These are cute illustrations of the importance of punctuation—but they’re not really what I’m focused on in this post. The commas in those two sentences change the fundamental meaning of the sentences; what I’m talking about is how punctuation can change the rhythm or inflection of prose.

If this all sounds esoteric, or unnecessary for non-writers to think about, consider that punctuation choices come up almost constantly when we write, whether we want them to or not. Another quick demo:

This is my favorite kind of post [, — : OR ( ) ] a deep dive on a super obscure topic. I began with a vague sense that I wanted to write about punctuation [. ; — OR …] I ended up with a 3,500-word essay [. OR !]

In fact, literally any time we want to join two independent clauses, we have at least four options for how to do so:

1. Drive faster. We’re going to be late.

2. Drive faster; we’re going to be late.

3. Drive faster—we’re going to be late.

4. Drive faster…We’re going to be late.

In this particular example, because the clauses are short (i.e., a comma splice is acceptable), we can add a fifth option:

5. Drive faster, we’re going to be late.

And because the second clause is not strictly necessary for meaning, we can add a sixth option:

6. Drive faster. (We’re going to be late.)

And because the second can be said to specify or explain the first:

7. Drive faster: We’re going to be late.

Of course, some of these possibilities are more viable than others. You probably have an intuition about which ones you like more or less—as do I. Still, they’re all allowed according to the rules of grammar. In the proper context, we could make a reasonable case for any of them. So how is a writer to decide between these seven marks?2

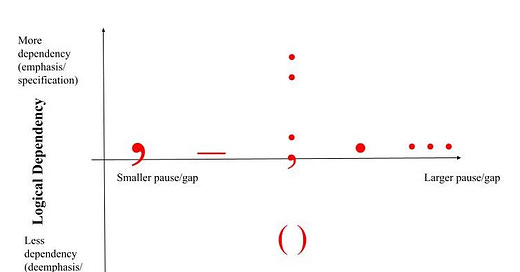

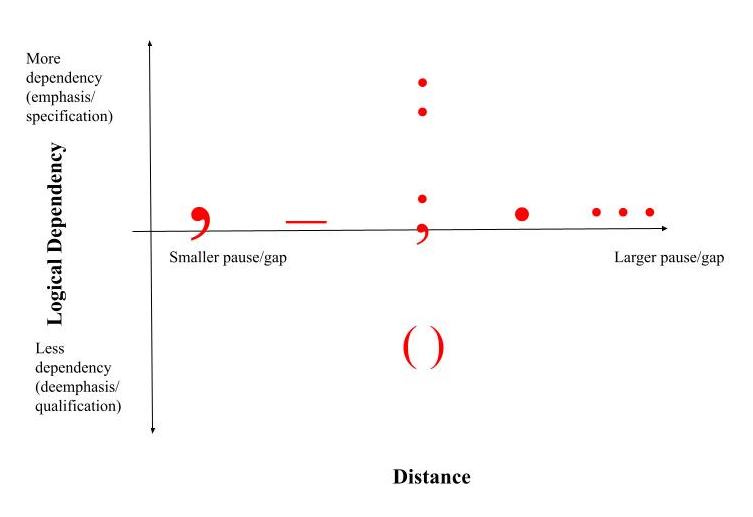

Glad you asked! I like to think about punctuation existing along two axes: a “distance” dimension, and a “logical dependency” dimension.

Of the two, the distance dimension is more straightforward to understand. It describes how long a pause or gap we should infer between two ideas—both in time (i.e., if we’re reading out loud) and in how closely related the ideas are. If a period implies a longish pause, for example, and a comma a short one, then semicolons and dashes are somewhere in between.3 Ellipses are extra long.

The logical dependency axis requires a bit more explaining. It’s about the extent to which one idea follows from the other (as suggested by the punctuation): how much the first clause “needs” or “predicts” the second. On this dimension, periods, semicolons, commas, ellipses, and dashes are all neutral by default—although the context can certainly imply causality or a hierarchy of importance. (e.g., In “Drive faster—we’re going to be late,” I hear the second half as more urgent than the first.)

Colons, however, always imply that whatever follows them is extra relevant or important: They hammer the point home. Or put another way: What comes after a colon should generally fit under what precedes it, conceptually speaking (e.g., Here’s my main point: This is an illustrative example.). This function is in contrast to regular periods (dashes, semicolons, etc.) which can link ideas in a hierarchical way—but can also set up a second clause that runs against, parallel, or orthogonal to the first one. Sometimes, following a period, a new sentence will simply locate a subtle current of sound or meaning and jet off in a new direction. Not so after a colon: Colons demand an explanation.

Finally, parentheses (by virtue of containing nonessential information) would seem to make a given group of words feel less important—at least in theory. In practice, the act of signposting a phrase with NOT IMPORTANT sometimes has the ironic effect of drawing extra attention to it—a kind of grammatical white bear problem or “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.” So while parentheses can indeed serve to deemphasize the information within them, they can also serve to undermine the information without them.

(At least, this is often how it seems to go for short parentheticals inside or immediately following regular sentences. For longer standalone parentheticals, especially those that comprise a paragraph in their own right, I think there’s a greater temptation to just skip over them completely…Then again, here you are still reading, sucker.)

In sum, here’s a visual representation of these seven punctuation marks, with “Distance” along the X-axis—from smallest pause/gap (commas) to longest (ellipses). The Y-axis really just helps account for two specific punctuation marks—both of them of middling “distance”: the colon, which implies extra logical dependency; and parentheses, which imply reduced logical dependency (but sometimes ironically so).

A few things to note about this visualization before we move on to the really riveting stuff. (Oh, yes! There’s more!)

First—an obvious but important point—punctuation is usually secondary to the impact of the words themselves. In the sentence, My son was normal except for one thing: He had three heads, for example, that second piece of information is going to jump out a bit no matter what kind of punctuation you use!

Second, keep in mind that the place I’ve put all the symbols on the graph is simply meant to represent their typical effect in writing. Some of them—especially that slippery little em dash—can be used for a lot of different effects. If it helps, you might imagine each punctuation mark with a “heat map” around it indicating its range of possible uses: a big circle for the dash, on account of its versatility; a small one for the ellipsis on account of its serving basically just one purpose (i.e., making you think your boomer boss is mad at you…) All these “heat maps” overlap a lot, but their centers fall in different places on the graph.

In the edge cases, though—that is, in situations where there really is a case to be made for multiple ways of punctuating—I find these dimensions really helpful to think about. If you’re deciding, for example, between commas, parentheses, and dashes (in a little aside like this)—or this—you might consider how significant you want the interruption to be, and what its relationship is to the rest of the sentence. Similarly, I often find myself debating between colons and semicolons: Do I want a hard emphasis; or a gentler, less prescriptive connector? Again, the graph helps make these microchoices more straightforward.

In fact, it is precisely because there is so much overlap of usage that it is beneficial to understand the typical effect of each kind of mark: They give the writer greater control with potentially ambiguous material. Fail to consider these subtle distinctions and you fail to consider how your words may ultimately be received.

Psychologizing Punctuation

“Everything that is said must be said in a certain way—in a certain tone of voice, at a certain rate of speed, and with a certain degree of loudness,” writes sociolinguist Deborah Tannen.

Tannen is referring to oral communication here—especially as it pertains to the workplace—but her observation is equally relevant to the written word. Punctuation is one of the few tools at writers’ disposal to control the how of their text’s reception, in addition to the what. (Other tools: fonts, capitalization, and formatting choices.)

Ordinarily, most of our choices about punctuation are made unconsciously. We might go back and forth about whether it’s too casual to sign off our email with an exclamation point, but we’re not generally making these kinds of decisions in between every single sentence. Maybe we should be.

As they accumulate throughout a text, punctuation choices convey important information about our characteristic ways of viewing and describing the world. Perhaps the easiest way to see this phenomenon at work is to look at sentences that are so extreme in their habits of punctuation as to begin to look pathological. Most types of punctuation cause issues if they are overused in too short a span of prose—for example:

The dash—with its various—and imprecise—uses—begins to feel sloppy—and choppy—as a connector.

Ellipses…so great for humor and suspense…so annoying if used over and over…and over…again.

(Parentheses (like ellipses) can break the flow of a text or suggest lack of conviction (especially if (cringe!) nested within one another).)

In the penultimate position: that champion of hierarchical thinking: the colon: Surely it’s a bit silly to drive home a point that is itself driving home a point: I rest my case.

Periods and commas are mostly an exception here since they are the “standard” connectors. Mostly. An exception, that is. But not, as I think, or hope, this last example will demonstrate, or imply, a complete exception!

To be sure, all these issues are partly just an aesthetic consequence of using the same trick over and over again—but I’d argue they also betray a more serious problem: an imbalance of thought.

The world, after all, includes relationships between ideas and objects of all different strengths and kinds: close and distant; hierarchical and egalitarian. A tendency to view the world in one of these ways can make a writer’s prose interesting and recognizable; a singular obsession elides the richness of reality.

Of all the nonstandard punctuation marks, the one least subject to overuse is, I think, the one I have yet to mention—the semicolon; multiple semicolons aren’t so bad; they’re not so different from periods or commas, after all; just make sure you’re ok sounding a bit pretentious if you go this route.

Problematizing Punctuation

Then again, perhaps this bias against semicolons is rooted in something less than admirable. As Parul Sehgal argues in the book review I cited at the top:

Semicolons…belong to the family of trills and volutes; they exist for the sake of complexity, beauty, subtle connections. Cardinal virtues, I’d say, but Watson traces the warring (and gendered) camps of prose style—a fixation on clarity and directness versus a curled sensibility, one interested in the fertile territories of ambiguity.

True, there is something gendered about the way punctuation can inflect language on the page! Consider, for example, this paragraph from Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral”—typical of so-called “dirty realism” and the hypermasculinized writing sensibility Sehgal is alluding to:

That summer in Seattle she had needed a job. She didn’t have any money. The man she was going to marry at the end of the summer was in officers’ training school. He didn’t have any money, either. But she was in love with the guy, and he was in love with her, etc. She’d seen something in the paper: HELP WANTED—Reading to Blind Man, and a telephone number. She phoned and went over, was hired on the spot. She worked with this blind man all summer. She read stuff to him, case studies, reports, that sort of thing. She helped him organize his little office in the county social service department. They’d become good friends, my wife and the blind man. On her last day in the office, the blind man asked if he could touch her face. She agreed to this. She told me he touched his fingers to every part of her face, her nose—even her neck! She never forgot it. She even tried to write a poem about it. She was always trying to write a poem. She wrote a poem or two every year, usually after something really important had happened to her.

What kinds of punctuation do we have here? Lots of periods, and quite a few commas. Two dashes. One colon. One exclamation point. (In the entire story, which spans fourteen pages, there is not a single semicolon—and there are certainly plenty of places they would be allowed.)

These choices reflect Carver’s own preferences as a writer, but they’re also a deliberate technique used to characterize the narrator, an emotionally stunted man who serves as a vehicle for much of the story’s artistic and comedic force: The guy’s thoughts come in discrete packets of declaration. He calls it how it is, we might say. He is, in more precise terminology, an asshole.

Note also the narrator’s casual deprecation of, and discomfort with, his wife’s poetry (“She was always trying to write a poem. She wrote a poem or two every year, usually after something really important had happened to her”). It is the punctuation here, in part, that gives these sentences their stiffness. (Consider, as a less staccato alternative: She was always trying to write a poem; a poem or two every year; usually after something really important had happened to her.)

When it comes to genre, the mention of poetry also gets us into gendered terrain, of course. In their interview with Toni Morrison, for example, Elissa Schappell and Claudia Brodsky Lacour reported that “Morrison detests being called a ‘poetic writer.’ She seems to think that the attention that has been paid to the lyricism of her work marginalizes her talent and denies her stories their power and resonance.”

Of course, Morrison is a poetic writer—it’s just that she’s also a lot more than that. (Among her many gifts: a facility with complex plots, a sharp ear for dialogue, and a knack for incisive social commentary that never condescends.) In light of this, you can understand why she might have found it annoying when people were singularly focused on how “poetic” she was…

Granting, then, that our perception of Morrison as a poetic writer may owe something to her race and gender, I still think it’s worth considering what features of her prose itself lead it to be stamped with such a label. Of course an artful and original use of language is one piece of it—but there’s also a role of punctuation, which Matt Bell highlights in his excellent post on the topic. Consider this fragmentary example pulled from Sula:

A sleep deeper than the hospital drugs; deeper than the pit of plums, steadier than the condor's wings; more tranquil than the curve of eggs.

I mean, come on—if that's not poetry, what is? Here’s Bell’s analysis:

Morrison uses semicolons to create a progression of thought and feeling, in this case dropping from level to level as the character falls into sleep, the punctuation working in concert with the intensifiers of “deeper, deeper, more” to invite us down through the felt layers of his slumber.

Bell also offers another example—a rare instance of a successful double colon—from Ursula K. Le Guin’s feminist sci-fi classic, The Left Hand of Darkness:

All those miles and days had been across a houseless, speechless desolation: rock, ice, sky, and silence: nothing else, for eighty-one days, except each other.

Of particular relevance to this discussion of punctuation and gender: The Left Hand of Darkness is about an alien people with no fixed sex. On the sentence level, I find the colons suggestive of this theme: The colons effect both a hierarchical relationship between the ideas and—by virtue of rhythm/repetition—a kind of poetry. Or in gender terms: a sensibility that is both “masculinized” and “feminized.” (Bell glosses it, “a houseless, speechless desolation OR MORE CONCRETELY rock, ice, sky, and silence OR MORE EMOTIONALLY nothing, for eighty-one days, except each other.”) While I doubt Le Guin would have put this in such explicit terms herself, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that she was both a distinctive punctuator and a prominent gender theorist. In this case, form truly does mirror content.

Before I traffic any further in stereotypes, let’s take a step back! I’m not saying, you know, Semicolons are for girls, colons are for boys (or whatever you’d like to consider the most “masculine” punctuation mark). Obviously that would be silly and reductive. Obviously people of all genders use all these kinds of connectors all the time.

But I do think that—fairly or unfairly—there are general patterns in how we perceive a person’s communication style with respect to their gender; these stylistic differences manifest on the page, in part, through punctuation choices. Not all the time, of course—and not often in a single sentence or paragraph. But enough that if you’re reading a lot of someone’s writing, or they’re making really unusual punctuation choices, their style can start to feel gender (a)typical.4 To use a “masculine” style as a man, in other words—or a “feminine” style as a woman—is to reify one’s own voice and identity. To use counterstereotypical punctuation, by contrast—or develop a style that is difficult to pin down—is to blur the lines between “the warring (and gendered) camps of prose.” Some revolutions are loud; others march to the quieter drumbeat of commas, dashes, and semicolons.

Not to Put Too Fine a Point on It…

So what’s the takeaway from all of this?

First, I think that most of the time, for most people, it makes sense not to lean too hard on any one kind of punctuation.

Again, this is primarily because I believe a variety of punctuation is (usually) a better reflection of the complexity of the world. It’s also because a variety of punctuation is more inclusive—in the grand political sense of the word, yes; but also just because if, say, some people like em dashes and some people hate ’em, a light touch seems like the best way to keep everyone happy?

Paradoxically, though, it is sometimes the unusual or extreme punctuation choices that actually make something great—especially in the realm of art. As Matt Bell puts it: “I’m enamored with these examples because of their contrast to what I was taught as ‘correct’: but if Le Guin and Morrison can punctuate in this way, why can’t I? Why can’t you?”

Ultimately, I’m not making an argument for any punctuation style over any other.

There are situations in which—for reasons as various as there are ways of thinking—syntactic complexity is—with respect to the writer’s particular objective—desirable: It can obfuscate; it can, alternatively, suggest nuance; it can, if employed with care in very particular instances, characterize a writer as someone in possession of a certain intrigue, panache, je ne sais—Ok, I think you get the idea…

And a simple style can be good, too. Unambiguous. Clean.

Still, no matter which style you’re going for, it’s surely worth knowing what all those little dots and squiggles mean: Even simple sentiments can be subtly inflected, after all; even a text message can have…~implications~. No matter how plain or pretentious we want our prose to sound, no matter what the occasion, we should strive to hit our marks with rhythm, balance, and intention. This—this!—is punctuated equilibrium.

TL;DR

Punctuation conveys not only the felt pacing and spacing of a text but also the implied connections between ideas; it reveals a writer’s tendencies and habits of thought.

For this reason, it is in our best interests to attend to subtle distinctions in punctuation in all forms of written communication.

Thanks to Malcolm for edits.

ICYMI, a confession: I did liberally change the boundaries between sentences in this demo, and I punctuated the penultimate one in a way that changed “this” to a different part of speech (from a pronoun to a determiner). I don’t think this is really in the spirit of the exercise, but did it anyway to exaggerate my point #BadBoy.

Of course there are more kinds of punctuation than these seven. I'm choosing to focus on these ones because I believe they present the most ambiguity. (In contrast to, say, quotation and question marks, whose usage is more restricted and clear-cut.)

On the note of semicolons and dashes, I could also imagine a third “formality” axis; I tend not to give this too much thought in my blog posts and just wax academic or slangy as the mood strikes me—but of course (in)formality matters in many kinds of writing, too.

It occurs to me that this is a basically empirical claim—i.e., do women, in fact, use more semicolons than men? Unfortunately, the only scholarly article I was able to find online about gender differences in punctuation was this 2005 study, which concluded that men are less likely to use apostrophes than women in instant messaging. The authors interpret that this is due to men’s increased willingness/privilege to violate grammatical conventions relative to women.

Punctuation can also have a big impact in marketing and other persuasive writing—no? I’m sure advertisers (and copywriters in general) think about this a lot. Interesting take!