This post is part of a miniseries. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 3 can be found here.

Although I have spent ample hours of my adult life rigorously assessing and figuring all sorts of human calculations, the “flesh math,” as we say, I retain an amazing facility for discharging to hope and dumb chance the things most precious to me. –Chang-Rae Lee, Native Speaker

I think the greatest error most of us commit in decision-making is satisficing when we should maximize or maximizing when we should satisfice.

Some people—let’s call them pathological maximizers—meticulously research and evaluate every decision, no matter the context. This is a mistake for several reasons, some of which I’ve already mentioned in Part 1: First, Maximizing is inherently crazy-making. Second, hard decisions definitionally are those which cannot be maximized because the options are on a par.1 Third—and probably most important—maximizing decisions can have a big opportunity cost, consuming time and resources that might otherwise be put toward choices that matter more.

Other people—let’s call them pathological satisficers—always jump on the first half-decent option that comes their way. These individuals may tend to be happier with what they’ve got,2 but their outcomes are objectively worse, and they are often sacrificing long-term success for a swift resolution. Satisficers can also be freeloaders (and I speak here as a not infrequent offender)—reaping the rewards of maximizers in their lives while bearing few of the emotional and administrative costs.

So this post—the most pragmatic of the series—is centered on two key questions:

How do we better recognize when to maximize and when to satisfice?

Whichever approach we are using, how do we make better decisions in practice?

Getting clear on the answers to these questions can help us get the best worlds of both maximizing and satisficing.

When Is “Good Enough” Enough?

I wish I could give a simple rule on when to shrug and when to make a spreadsheet. Unfortunately, decision-making is a highly personalized art, so there is no formula. Instead, when it comes to maximizing vs. satisficing, what I can offer is this: one trite reminder, and one framework that I’ve found useful.

The trite reminder is that decision-making is a skill like any other. (Repeat after me: The door is only a door.) Like all learnable skills, it is therefore improved through deliberate practice, with tight feedback loops and frequent self-reflection/evaluation. You might find that certain environments are conducive to this because they are gamified or have lower stakes. You might find that keeping some log of decisions leads to insights about how to make them better.3 This increased attention alone will help hone your intuition of when to maximize and when to satisfice.

The framework is one which builds on Ruth Chang’s distinction between big versus hard choices introduced in Part 1:

All else equal, satisfice for small decisions and maximize for big ones.

All else equal, satisfice for hard decisions and maximize for easy ones.4

And when you face conflicting pressures along these dimensions, “maxi-fice”—i.e., maximize, then satisfice (more on this at the end).

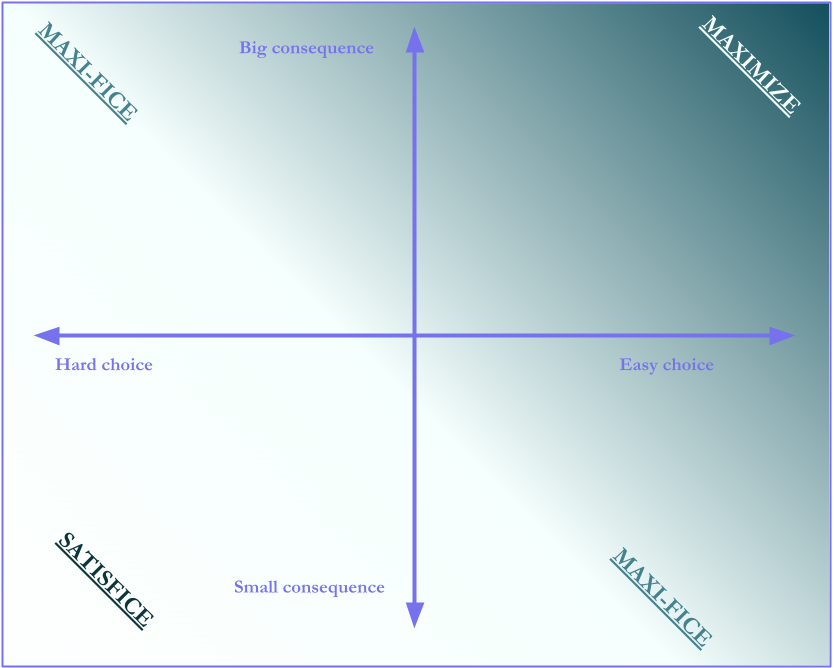

Here’s a visual of the framework:

Of course, what makes a decision “big” or “hard” is relative to your own values. (This is what makes it a decision-making framework rather than a rule or formula.) Still, let’s quickly run through the four quadrants with some examples from before that, I hope, will align with common-sense perception.

In the bottom left quadrant, we have hard + small choices; this is the “ordering a dish at a new restaurant” corner. Here, the trap is trying to maximize at all: The stakes are very low, and the decision is virtually impossible to maximize (since taste is subjective and inherently difficult to describe in words). If you find yourself in a situation like this, your goal should be to simply make the choice with as much speed and confidence as possible.

In the top right quadrant, we have big + easy choices; this is the “getting a life-saving operation” corner. Here the trap, if anything, is in not maximizing enough—for example, by letting yourself be swayed by superficial factors like a doctor’s bedside manner rather than looking at e.g., surgery success rates. If you find yourself in a simple high-stakes decision and you have good data available, it’s best to just trust the numbers.

Finally, there are the choices in the mushy middle (represented here by the diagonal from the top left to bottom right): big + hard choices and small + easy choices; these are the “finding a long-term romantic partner” and “changing a dead lightbulb” corners, respectively. In either scenario, it can be tempting to go all-in on maximizing or satisficing—albeit for different reasons.5 However, the wisest approach is probably a hybrid one.

With this framework in mind, let’s now turn to the second question of this post—how do we make better decisions in practice?—starting with how to be a better satisficer.

Satisficing Protocols

I’m discussing satisficing before maximizing for two reasons.

First, it’s my observation that a lot of decision-making advice is already focused on how to get better outcomes (i.e., maximizing) when the more difficult challenge really is learning how to be content with the outcome you’re choosing (i.e. satisficing).

Second, I suspect that when they really have to, most satisficers can turn it on. If push comes to shove, in other words, even people who choose their outfits at random will reluctantly compare mortgage rates and salaries for competing options; by contrast, a lot of maximizers struggle to satisfice even when there is every indication that they are wasting time or making themselves miserable.

In short, the purpose of satisficing protocols is to move the decider(s) toward a choice with greater speed and enthusiasm. Mostly this is a matter of getting out of the way of our System 1/elephant and letting it do what it does best: form general, intuitive impressions. While this certainty is arguably a kind of cognitive illusion—one which can lead us astray when real analysis is required—it is a helpful compass by which to make a low-stakes decision and move on.

How do you get a stronger signal from your gut? The answer basically boils down to visualization. I mean visualization broadly here, in the sense of “form a holistic (literal or metaphorical) picture of each of the options.” This often entails an exercise of imagining yourself into each of the situations (what does it feel like taking your first bite of Taco Bell vs. your first bite of Sweetgreen?), or verbally distilling each option into its core brand, essence, or “meaning.” The goal is to deliberately simplify the decision; to play the believing game with each of the options, judge them in gists and gestalts.6 You might simulate the way each one feels in your body, its particular flavor and texture—perhaps toggle back and forth between them in your minds a couple times. Then choose.7

If you’re really under the gun to make a quick decision—one which you know isn’t worth your time to fret over, but are nevertheless stuck on—a good forcing function is to flip a coin. However, the point of the coin flip here is not to relegate the choice to chance but rather to reveal your intuition. If, for example, you’ve designated heads as Sweetgreen and realize you’re craving Taco Bell the minute you see Lincoln’s face, then go with your gut—not the coin.

Similarly, when a group is making a difficult but low-stakes decision, you can use our psychosocial biases (i.e., groupthink) to your advantage. As a general rule, humans are subject to influence and averse to conflict, so once you have a solid option, it’s often possible to get a snowball rolling around it. A protocol which structures the choice set can help groups generate this momentum more efficiently. For example, when making a choice with one or two other people, I’ll often use a “5-2-1” protocol like this:

I pose 5 restaurants for dinner.

You narrow the set down to 2.

I (or a third friend) selects 1.

This is a satisficing protocol because it produces an outcome above a threshold, rather than optimizing for “mean satisfaction” or something like that; everyone has a veto on the option they hate. Nor do I think there’s anything magical about the numbers 5-2-1. (If I were in a group of four I might do 6-4-2-1; if I were in a larger group I might have everyone generate a list of 10, then go around and let everyone eliminate one at a time.) The point is simply to a) get buy-in from all stakeholders and b) transform the choice from one open-ended question into a series of simpler sortings.

Finally, in groups where people are shy about their opinions or don’t know each other very well, there’s a magic phrase I recommend: “I don’t have a preference, but I can form one if that would be helpful.”

This phrase is useful because group decisions present a coordination problem: Most people don’t want to dominate the process—but once someone has voiced an opinion there’s a decent chance the group will latch onto it (whether because of conflict aversion, true indifference, or laziness). For this reason, conscientious participants in a group decision are often reluctant to speak too soon. In effect, voicing an opinion in a group like this is saying, tacitly, I believe my preferred option may well secretly be the most popular one, or, My preference/knowledge in this domain is strong enough that it should steer the group.

The beauty of “I don’t have a preference, but I can form one if that would be helpful,” is in signaling that if there is anyone else in the group who suspects they have greater expertise or stronger feelings, now is the time to speak; if everyone passes, then you can in good conscience offer up an option—which the group is more likely than not to roll with—even if you didn’t initially believe you were the best person to do so.

Maximizing Protocols

My advice for maximizing well can be boiled down to three words: Aggregate independent judgments.

The first mistake people make in this domain is in failing to lay out criteria before actively choosing. Defining criteria should itself be a decision made independently of the main decision—i.e., before we are in the thick of a project or intensive search. Instead, we often go into a decision with a hazy sense of what we want, and then let the choices before us dictate what we value.

Of course, it’s a fantasy to believe that you can always distill your values in the abstract and just go out in the world and find your dream job, or soul mate, or whatever it may be; defining criteria does require a certain amount of experimentation, learning the market, etc. But too often, we don’t do any decision preparation at all, and this leads to distortions or mission creep: We might want to buy a new car for the purpose of a long highway commute, for example, and get swayed by shiny add-ons like all-wheel drive or a sun roof; if we’d taken a beat beforehand we might instead have realized that miles-per-gallon was the most important variable.

The second major mistake people make is taking a holistic, satisficing approach to choosing when they should instead break the choice down into discrete sub-decisions. In the car example, this might be judgments of price, gas mileage, comfort, safety, and storage capacity. You might create a rubric or formula that weights each of these factors in rough proportion to what you care about, then spits out an overall score. The key here is that as much as possible, you should be looking at each of these as a choice on its own—NOT worrying about how you will add all the factors up until you reach the end.

It’s nice to imagine that when we make an intuitive judgment, this really is just the unconscious equivalent of a rubric—the “score” of weighting formula in our heads. In fact, our off-the-cuff takes tend to be quite poor if they’re not carefully structured; our minds crave certainty, and inevitably when we make a holistic judgment we gloss over many of the tradeoffs and uncertainties we would have found had we forced ourselves to dig into the details. This goes some way toward explaining why maximizing feels worse than satisficing: In a hard choice, neither option is universally better, and maximizing forces us to attend closely to the areas we are sacrificing. The right choice is rarely the perfect choice.

The same principle of aggregating independent judgments holds true in group settings. Here, there is an additional social explanation for why decisions may go awry: information cascades. (This example, a description of deliberation over a job candidate named Thomas, is taken from the book Noise):

Arthur…suggests that the best choice is Thomas. Barbara now knows Arthur’s judgment; she should certainly go along with his view if she is also enthusiastic about Thomas. But suppose she isn’t sure about who is the best candidate. If she trusts Arthur, she might simply agree: Thomas is the best. Because she trusts Arthur well enough, she supports his judgment.

Now turn to a third person, Charles….Charles’s own view, based on what he knows to be limited information, is that Thomas is not the right person for the job and that Julie is the best candidate. Even though Charles has that view, he might well ignore what he knows and simply follow Arthur and Barbara…He may simply think that both Arthur and Barbara have evidence for their enthusiasm.

Unless David thinks his own information is really better than that of those who preceded him, he should and will follow their lead. If he does that David is in a cascade. True, he will resist if he has very strong grounds to think that Arthur, Barbara, and Charles are wrong. But if he lacks those grounds, he will likely go along with them.

A couple paragraphs later, the authors drive the key point home:

The trick in this example is that Arthur’s initial judgment has started a process by which several people are led to participate in a cascade, leading the group to opt unanimously for Thomas—even if some of those who support him actually have no view and even if others think he is not the best choice at all.

In this example, it’s important to note that Barbara, Charles, and David aren’t (necessarily) just mindless sheep; they may well be responding rationally to the signals of those who spoke before them. They may be truly ambivalent, and the opinions of their colleagues are enough to tip the scale in Thomas’s favor. This kind of snowball is exactly the dynamic you want to catalyze when, e.g., you are shepherding a group of friends toward choosing a restaurant—and it is exactly the dynamic you want to avoid when you contemplate a highly impactful decision.8

How does one avoid information cascades? Just as forcing yourself to make a series of discrete sub-decisions leads to better overall choices in the personal domain, forcing individuals to make truly independent judgments leads to better overall choices in the group domain. The easiest way to do this is to require people to write down their views separately, then combine the votes or estimates. And if you must have people deliberate publicly (which naturally is an important part of group decision-making) then have them write down their views first, then deliberate—and then ideally write down revised views after deliberation.9

And again, as with individual decisions, you can also use a tailored weighting or formula that incorporates people’s judgments in proportion to their expertise or stake in the decision. If, for example, your startup is hiring its first full-time engineer, you might have the whole founding team interview candidates independently but count the CTO’s rating double, since the CTO will be working most closely with the new hire.

Finally, there are two other invisible “independent judges” you can consult to maximize your decision—though they may not be available in all situations: the outside view and yourself at a different point in time.

The outside view is Kahneman/Taversky’s term for invoking a reference class as a benchmark for your judgment. Essentially you ask yourself “If someone else were making the decision, what would I predict/advise?” Often, when you do this you’ll find that your answer is considerably less optimistic and more objective than when you are just asking the question of yourself. (Common “inside view” fantasies include overestimating the odds of your success and underestimating how long it will take you to complete a project.) The outside view shouldn’t swamp your inside view entirely—after all, it’s possible you really are special—but it should give you pause. And if the outside suggests a wildly different answer than your inside view, you should discount your (likely biased) perception by adjusting your projections toward the outside view.

Asking yourself the same question at different points in time works because, as I recently argued, ideas are less like a lightbulb going off and more like pulling marbles from a bag: In other words, there is a kind of probabilistic distribution in the mind, and the average of two estimates tends to be more accurate than either on its own. (This effect, known as wisdom of the “crowd within,” gets stronger when the two judgments are made with greater time in between them.) All of this is a fancy way of saying that when you have a big decision to make, it’s worth revisiting it a few different times in a few different contexts or states of mind; you may find that the choice looks different in different light, and this can help triangulate the true best option.

You can probably see now how “aggregate independent judgments” is a principle which applies to maximizing at every scale of decision-making—just to summarize:

As much as possible, establish criteria before actively choosing.

Similarly, decide in advance how you will weight these criteria.

Use these criteria to break the choice down into discrete sub-decisions.

When making a group decision, have all individuals follow the above protocols separately before group deliberation.

If possible, consult an outside view (external reference class) for the decision.

If possible, return to the decision at multiple points in time.

Maxi-ficing Protocols

Although most of us tend one way or the other, no one is entirely maximizer or entirely satisficer. This turns out to be a good thing, because a lot of decisions require a blended approach. (In the graph at the top: the diagonal from the top left to the bottom right—a.k.a. big + hard choices to small + easy choices.)

However, in order to get the best results, it is important to blend maximizing and satisficing in the right way: Maximize first, then satisfice. There’s a reason, in other words, that I titled this section “maxi-ficing” and not “satis-mizing.”10

Maxi-ficing doesn’t require as much explanation because it really just entails successively applying the protocols described above: First, take an analytical approach, aggregating independent judgments and discrete subdecisions; next, hold up the options in your mind, visualizing them as concretely and holistically as possible. Once we’ve done the work of maximizing, this visualization step serves to tie a bow or put a stamp on the decision.11

What’s remarkable is that when we defer intuition in this way until the end, our judgments actually get a lot better than they would be off the cuff. Here’s Daniel Kahneman describing this on Hidden Brain, in the context is an evaluation for army service:

You run the whole interview, just and you generate those scores independently, fact-based and so on. Don't think of anything until the end. And in the end, close your eyes and give a score. How good a soldier will that person be? Now, much to my surprise, that intuitive score is really very good. I mean, it's as good as the average of the six traits, and it's different, so it adds content. So having an intuition, if you delay it, it's quite good.

So in fact, what I said earlier isn’t quite right. In fact, our intuitive judgments are the unconscious equivalent of a rubric our minds. It’s just that our minds have to be properly calibrated—each component of the formula inspected on its own—in order for the rubric to be reliable.

In short, maxi-ficing helps avoid the pitfalls of maximizing and satisficing on their own—neither throwing reason out the window nor devolving into a patchwork of tradeoffs and conflicting sub-decisions. The patchwork analysis, frustrating as it can be, is important; it’s what allows us to make apples-to-apples comparisons and say which choice is better on net. But in the end, it is the psychologically crucial move of stepping back which crystallizes the decision, aligning head and heart, elephant and rider. Making the “right choice” is of little use if you’re unable to act on it.

One of my favorite shorthands for this idea is Emily Oster’s “There’s no secret option C.” This is paywalled, but the basic idea is that consciously or unconsciously we are often waiting around for a miracle option that requires no tradeoffs. In the real world, usually we can’t have e.g., quality and affordability, excitement and consistency, etc., so rather than wait around for “option C,” we should choose between the A and B we’ve got.

Actually, perusing Google Scholar, I learned that even this finding is somewhat contested—or at least has a few caveats. But there’s almost certainly a strong version of the claim that’s true: Maximizers who know a domain well and use good decision-making protocols get better outcomes in that domain.

In particular, for maximizers, I think it can be helpful to assess which instances of maximization are actually leading to better outcomes. Is the ten minutes of deliberation spent choosing an appetizer in fact leading to noticeably tastier dishes than the times when you force yourself to go with your gut choice?

“Satisfice for hard decisions” is in fact a rebrand of an idea introduced in Part 1—namely that hard choices are easy choices; to satisfice a choice is to make it “easy” in the sense that you are deliberately not overthinking it or expending energy evaluating the best possible outcome.

In the arena of love, we might suffer from analysis paralysis (i.e., overmaximizing), creating an extensive list of criteria by which we evaluate every possible suitor—or we might throw reason out the door and completely trust our heart. In a low-stakes decisions like whether to change a lightbulb, it wouldn’t be such a grave mistake to totally satisfice; however if the decision is truly an easy one then it should be very cheap to do a bit of “maximizing” (in this case, a five-second pause to consider other relevant factors such as, e.g., whether there are multiple bulbs that need replacing, or whether the lamp for said lightbulb is actually plugged in).

I think there may actually be some cases where “satisficing” in this way can produce better outcomes than explicitly maximizing, likely because it taps into a kind of unconscious knowledge or pattern-matching. (These cases are the exception rather than the rule, requiring an environment that gives frequent feedback and expert intuition.) For example, one sometimes hears about exceptional judges of talent with a nose for great employees or startups; to the extent that this ability is real, satisficing trumps maximizing because there are too many contributing factors in success for the conscious mind to hold.

For the biggest decisions, it might seem difficult to distill and visualize when so much is packed into the choice and the future is uncertain. But even here we can try to crystallize paths or future versions of ourselves based on what matters most. (Note that for big, hard decisions, I recommend you do this after maximizing.) Here’s economist Sendhil Mullainathan describing how this approach might work for choosing between two jobs:

I think the biggest error people make is they think they are choosing for who they are right now. What they’re actually choosing is for this person five years from now, who’s going to be very different from them…If you think that you’re changing, what do you change towards? You change towards the people around you. So what you should ask yourself is, “I am going to become like the people at company A or like the people at company B. That’s who I’m actually going to become. Which of these kinds of people do I want to be as a person?”

It’s interesting to note that confirmation bias is really a kind of internal information cascade in one individual: You find yourself weakly drawn to one option over another, and then you start piling on all other kinds of reasons why it is the best choice—even though your initial preference was lightly held (just as David, Charlie, and Barabara follow along with Arthur’s initial preference in the example from Noise).

This “estimate-talk-estimate” protocol is also known as the Delphi method.

Admittedly, it’s a bit clunky to combine the words either way, since “satisfice” is itself already a portmanteau (of “satisfy” and “suffice”).

I’ll have more to say about this two-step in Part 3. As a teaser, a good mnemonic for maxi-ficing (which again I owe in part to Ruth Chang) is DOOR: Define the criteria; Optimize all sub-decisions; Open yourself to commitment; and Remake/realize yourself.

How to Choose (Part 3)

This post is part of a miniseries. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 2 can be found here.