No one’s really that great. You know who’s great? The people that just put a tremendous amount of hours into it. It’s a game of tonnage. –Jerry Seinfeld

If you want to have good ideas, you must have many ideas. –Linus Pauling

Imagine you decided to try your hand at some new creative endeavor—say, oil painting.1 You watch a couple YouTube videos, buy your materials, then sit down to make your first real piece.

To your surprise, friends and family greet this effort not with the mild affirmations you’d expected but overwhelming, effusive praise. Worried you’re being pranked, you show the work to a local art historian—whose reaction is, if anything, even more extreme: She extols your singular vision, fine craftsmanship, and attention to detail. A few months later, when your creation sells for many several thousands of dollars, you are as stunned as anyone.2

The question is, how should you interpret these events: as beginner’s luck, or a sign of preternatural talent?

I don’t mean this rhetorically. I mean, literally, how would you know, from your one painting, the degree to which luck or skill was the cause of your success?

To be sure, few if any individuals’ success is explained entirely by luck or entirely by skill. No doubt, in this hypothetical, you have some innate talent for painting. But just how much, and just how much that talent might be further developed, remains unknown.3 In fact—though we usually don’t think about creative work in such terms—this is essentially an empirical question: The real way to know how good your piece is in the scheme of your oeuvre is to make more stuff.

Inspiration, when it strikes, feels singular and mysterious; we crave these eureka moments because they seem divinely sent. But a less mystical view of creativity is less precious about the genesis of ideas. Our insights only feel singular because we don’t have access to all the other thoughts we might well have had in their place. In reality, there are all kinds of random events in the world around us and stochastic processes in the brain—so idea generation is, if not entirely random, then certainly probabilistic.4

In other words, inspiration is less like a lightbulb going off than like pulling a marble from a bag. The marbles in this bag vary in quality (gold, silver, bronze, and lead, let’s say—with various alloys in between), and different individuals vary in their ratios of marbles. The fewer marbles you pull, the less information you have about the underlying ratio.

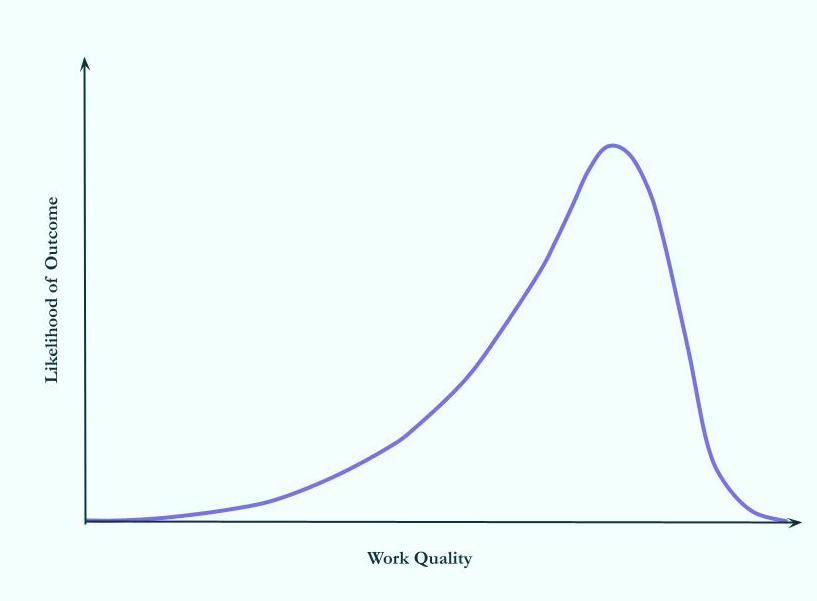

So, concretely, in the case of your overnight painting success, it’s impossible to know whether you’re doomed to chase the ghost of your debut:

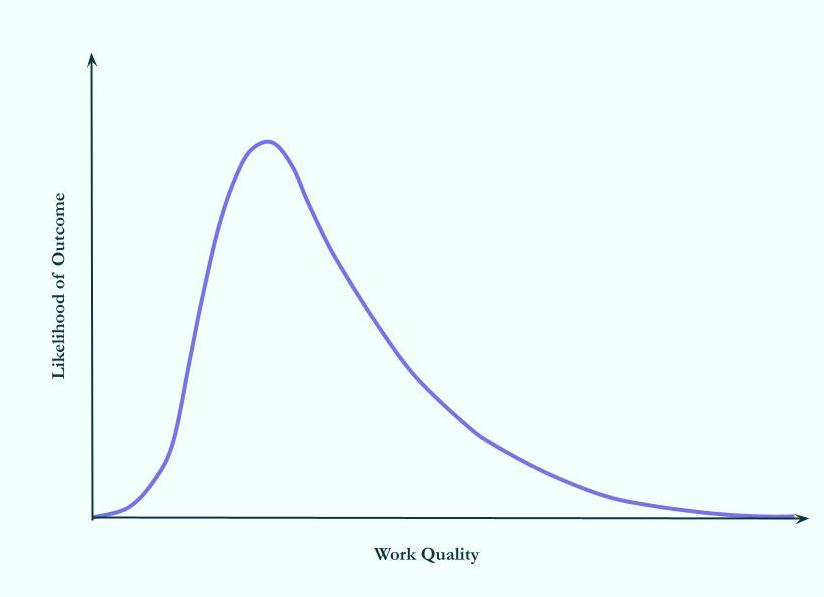

…or whether this is only the beginning of a storied career:

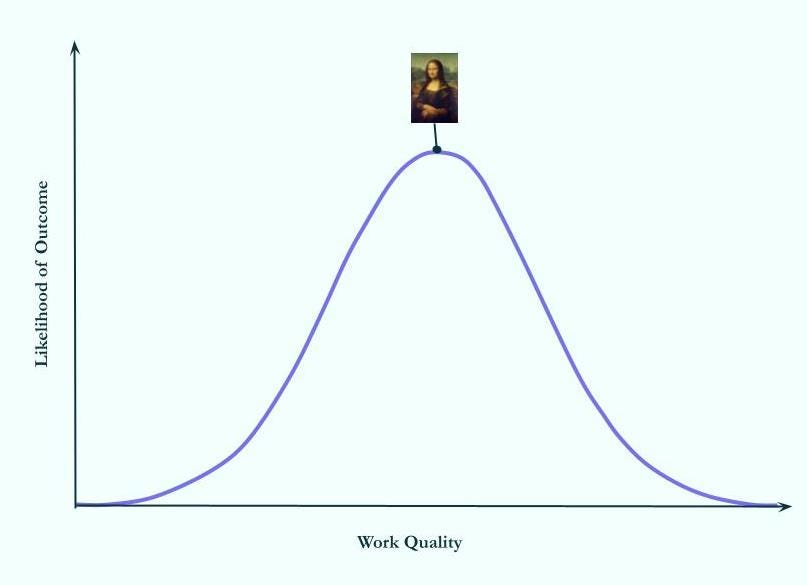

…or whether the painting is exactly representative of your abilities:

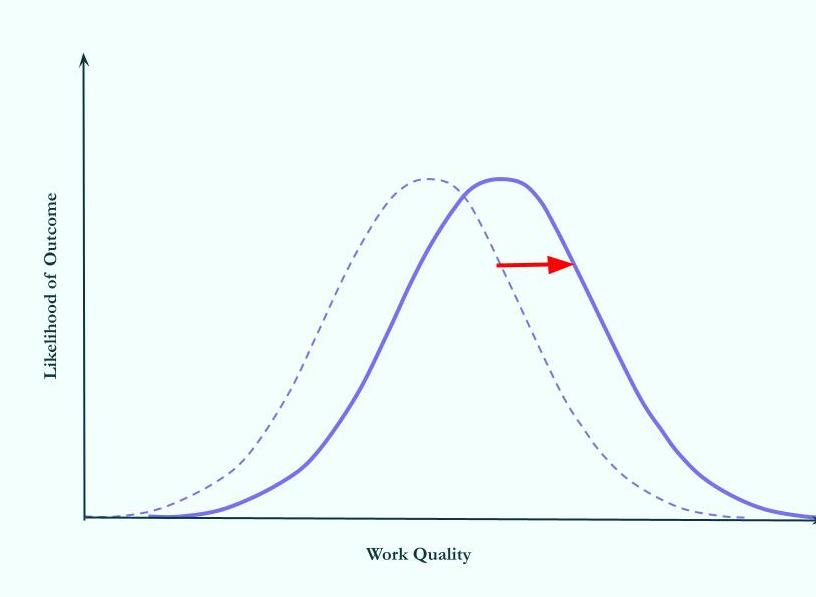

But of course “your abilities” is not itself a static distribution. With practice, you can shift the probability mass to the right—increasing the ratio of gold and silver marbles to bronze and lead ones. So in fact, making more paintings has two benefits: It both gives you more opportunities to beat the odds; and it improves the underlying odds themselves

But I’m making some implicit assumptions here. We don’t actually know anything about the shape of the idea distribution—the starting ratio of marbles in the bag. There’s no law that says idea quality has to fall on a bell curve at all! It could be that creative work tends to be either great or terrible:

Or it could be that the distribution is skewed, with several times as many gold and silver marbles as bronze and lead ones:

Sadly, I suspect that for most of us, the situation is reversed: Most of our ideas are below average, with a few outlier successes pulling the distribution to the right.5

Of course, with this distribution, or any of the previous ones, it’s always possible to get an outlier success. Someone somewhere has to buy the winning lottery ticket. But probabilistically speaking—and this is especially true assuming a positive skew—the good ideas are rare and the great ideas are rarer still. Your best strategy is to keep drawing marbles until one comes up gold.6

So far, my story has explained success simply as a product of “good ideas”—of course there are many more factors. But I think the basic conclusion still holds if we consider the whole causal chain, including things like:

The concept for a piece of work

The skill the creator has to execute the work

The effort the creator puts into the work

The reception of the external audience

Of these four factors, only one can really be said to be improved by greater attention to quality: #3 (effort). For the others, you’re much better off optimizing for quantity: #1 (concept) and even more so #4 (external reception) are only minimally controllable by the creator; all one can do is try and get more shots on net. #2 (skill) is much more so a function of repeated, deliberate practice than focusing intensively on any one project, as research and common sense alike support. Ironically, then, the real way to prioritize success might be to focus less on quality in any individual instance.7

It’s not that quantity or volume of output is itself evidence of greater skill. Rather, quantity is the only coherent response to the recognition that there is always some degree of luck in human endeavors—a defense against the charge that success was “only” luck. If you flip a coin ten times and get ten heads in a row, that’s luck; if you flip a coin ten thousand times and, on flips 6,234 – 6,243 get ten heads in a row, you have created better conditions for luck.

Of course, the inevitable cost of volume is an ever-growing collection of duds—that’s just basic math. Viewed in isolation, these duds are a failure; but viewed in the context of all the other work, they are the yardstick against which success can be measured. Repeatable success demands quantity, and greater quantity implies more failures.

In this sense, failures aren’t just a necessary evil—they are the best and only evidence you haven’t lost your marbles: Only an insane person expects to win on the first try.

As always, feel free to substitute in your activity of choice (e.g., screenwriting, entrepreneurship, academia).

While this zero-to-one hundred scenario is obviously fanciful, it is true that in some domains, people can achieve outsized success with relatively little experience. (Child actors, social media influencers, and Rebecca Black all come to mind.)

Jackson Pollock—that perennial victim of “My five-year-old could have done that” charge—is a perfect demonstration of this principle. Pollock’s struggle to paint for almost two decades preceding his famous “drip paintings” is proof that no, in fact, your five-year-old could not have done that. (Surely Pollock would have produced such successful work from the start if he could have!)

Of course, it is difficult to prove that any given idea is only one of many which could have arisen. However, we see some evidence for it in the crowd within effect: When one person estimates a value at two separate points in time, the average of those estimates tends to be more accurate than either individual value. This suggests that there is not one “true” answer our mind produces but a cloud of possibilities our mind selects from.

We see some evidence for “most ideas are bad” in the power laws that govern success in creative fields: The most successful artists are many orders of magnitude more successful than the typical artist, and their best work is many orders of magnitude more popular than their median output. (This fact only becomes more true if we consider all the bad ideas that are filtered out before they see the light of day.)

The research on creative success supports this conclusion, as I’ve written about before: Creators have better outcomes when they produce on a regular basis and have a greater variety of work in their portfolio.

All else equal, this probably means that those early in their career—i.e., who have more years ahead to reap the fruits of increased skill—should place an even greater emphasis on sheer volume. (This strategy assumes you are trying to optimize for the highest peak work—not necessarily the best median output.)

Personally, I think luck is the most important variable in life. Sure it's important to be good and to work hard, but many people who have achieved great success, particularly in business, fail to give credit to the luck fact. Lot's of people are talented and work hard. That's not enough to succeed although its a good start.