Wild Geese

by Mary Oliver

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.Every fall, at the high school where I used to teach English, parents came in for a back-to-school night. In the ten-minute block I had them in my classroom, I’d usually do a mini-activity (e.g., a debate, or the “notice/interpret” exercise I describe here) to give them a taste of a typical day. One year, at the end of one of these back-to-school nights, a dad raised his hand.

“So if you had to say what the core skill students learn in this class,” he said, “that would be…?”

I thought about the question for a moment. “Literary analysis,” I said, and left it at that.

I don’t think this parent was being rude—I think he was trying to understand what the methods of English are, in the same way that “algebra” or “trigonometry” are methods of math. What exactly would they know by the end of the year that they didn’t know before it? It can be tempting to reduce “literary analysis” to “making stuff up about a book”—and in a sense, that’s all analysis is. It’s just that there’s an art to the making up.

As it turns out, students themselves struggle a lot at the beginning of high school just to grok what teachers mean by “analysis.” Some never get there. The struggles tended to come in one of two forms: Most common are students whose “analysis” is obvious—so obvious, in fact, that their writing is basically just summary. These students write thesis statements like, “In The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison uses the symbol of blue eyes to symbolize white beauty standards”—which, if you haven’t read it, isn’t an argument so much as what the book is about.

Other students, seizing on the idea that their analysis should prove something debatable or controversial, swing to the other side of the pendulum. For example, I once had a kid in my class who proposed the thesis statement (and I promise this is verbatim, or as close to verbatim as I can do from memory): “In The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield is actually Jesus.” This student was not making an argument that the book’s narrator is a martyr or possesses Christ-like qualities. He was claiming that Holden is, literally, the divine son of God.

Real literary analysis, when it’s good, lies in the middle of these two extremes. It is both nonobvious and grounded in details from the text everyone would agree on. This tension can be difficult for students to recognize because when you read a polished essay, the argument flows so naturally that by the time you reach the end it seems as if nothing else could be true. So the real challenge is getting students not to expect that arguments will arrive fully formed, and therefore rush their analysis—which, inevitably, leads to ideas that are either obvious or unfounded.

In fact, the finished essay should be the culmination of a process of analysis that went into it, and the teacher’s task is to make that process visible.

Once I’d distilled the problem this way, my job got a lot easier: All I needed to do was show students how to build connective tissue between the obvious and nonobvious. As it turns out, the methods for doing this are both extremely simple and quite powerful—I use them myself to this day.

Method #1: The Ladder

In the “ladder” method of analysis, each rung is a statement or observation about the text, and each step up is a question. Eventually, through iterative “climbing,” you end up somewhere quite different than where you started. Crucially, though, you can always retrace the precise steps that led from A to B.

Let’s see how this works using the example of “Wild Geese,” the poem at the top of this post.

[A warning that this sample analysis, and the one in the following section, are deliberately a bit exaggerated: I didn’t want to cheat by choosing a poem about which I already had a prefab argument, and I’m erring on the side of hamming up how the methods work.]

Usually, I find it fruitful to follow one’s natural curiosity and focus in on whatever part of the text seems most strange or surprising. For me, that part is the word “pebbles” in the line “Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain / are moving across the landscapes.” This is the first rung of my ladder.

Why would Mary Oliver use the word pebbles to describe rain? A few explanations come to mind. It could simply be that “pebbles” is a more vivid word than “drops,” or that she prefers two syllables to one. It could be that “pebbles” ascribes the raindrops a sense solidity. Let’s try taking this answer as rung two.

Are there any other places in the poem where solids and liquids seem to blend? Indeed there are: “over the prairies and the deep trees” [emphasis mine]. To call the trees “deep” rather than “high” is to see them from the geese’s perspective—from above. It is also to them as a sea or lake, a fluid body which can be plunged into. Another rung.

Why would Oliver be interested in blurring the boundary between states of matter? In light of the final line that all of us have a place in the “family of things,” perhaps there is an insight here about fundamental nature of reality: When you strip away human perception, the universe is simply molecules in space. “Liquid” and “solid” are the mind’s projection of physical reality.1

Now we’ve ended up somewhere quite different than the place we started—ascended rung by rung from micro-observations about the text to a broader thematic claim:

The final, high school English-y sleight of hand is to flip the ladder around so that the endpoint is the one which starts the analysis. In this case, we get something like:

“Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver blurs states of matter to highlight the illusory nature of human perception. For example, in the lines, “the clear pebbles of the rain / are moving across the landscapes,” the word pebbles suggests that the raindrops are a solid object. Similarly, the description of “deep” trees portrays the forest as a body of water. The cumulative effect of the poem is a recognition that the “family of things” extends to matter itself: the raindrops and the trees, the geese and the human mind—all are equally composed of the same stuff of the universe, linked at a cosmic, atomic level.

It’s worth noting that to get to this final analysis, we had to reject some lines of questioning which did not yield the most fruitful answers. This is the metaphorical equivalent of backtracking to a lower rung and ascending by a different route.2 In the final version, we can also often get more propulsive analysis by “skipping rungs”—that is, making quicker leaps from claim to claim to give the reader the experience of mini-epiphanies. (Conversely, in more technical or pedagogical contexts, it’s useful to include the entire chain of reasoning.)

Ultimately the ladder is just a way of structuring thought to get from somewhere you know to somewhere you don’t.

But what should you do when you’ve simply got a hunch of where you’re going?

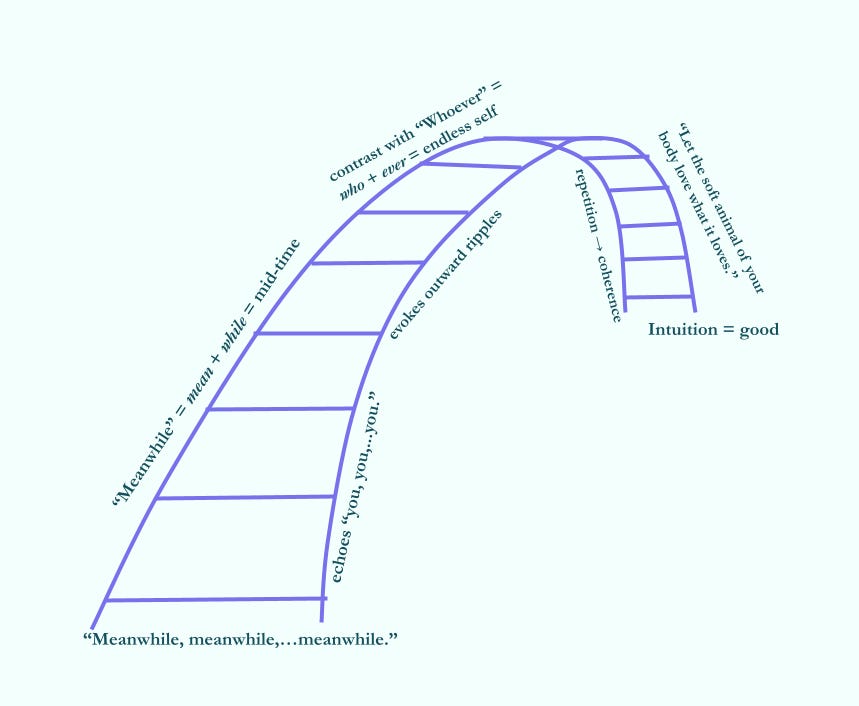

Method #2: The Bridge

The bridge method is a little less structured than the ladder but, in my experience, a more rewarding way to read and write. It starts by choosing two features of the text you suspect are related or think could be related, but have not yet worked out how. Then, in a state of relaxed attentiveness, you simply let the brain exercise its natural capacity for finding patterns and making meaning—or dare I say: let the soft animal of your body love what it loves?

For this example, let’s again choose a small formal element of the poem and link it to a broader thematic message: the repetition of the word “meanwhile”; and the suggestion to trust one’s intuition.

How might we build a bridge between these two points? Here, the process resembles the ladder method, but you can come at the problem from either direction—adding rungs (planks?) from either side until the analysis syncs up in the middle.3 I find this has more of a mind-wandering quality than the iterative question-answer-question-answer ascent of the ladder, but I’ll try to lay it out linearly here.

If we focus in on the placement of the word “meanwhile,” we’ll observe that it’s repeated twice in quick succession, then a third instance a few lines later. Like an echo, this evokes time rippling outward from the present: this moment, then the next one—then, some time in the future, the next one; meanwhile, meanwhile…meanwhile. This pattern of repetition is also mirrored at the start of the poem with you, you…you. The implication is that the you who is here now will evolve, continuously and imperceptibly, into some you and now of the future.

Already, this is starting to feel like a somewhat pro-intuition stance—the two sides of the bridge connecting.

How can we strengthen this line of analysis? Here, I find it useful to say to myself, “Let’s assume [author] is a genius who infused their text with a secret message. Where do we see clues pointing toward that message?” This isn’t because I think the author actually intends to convey a secret message (often, they themselves may not know on a conscious level what they’re trying to do), but because this given opens my mind to more examples. It’s the difference between being told, “What do you see in this picture of a tree?” and “There are three faces hidden in this picture of a tree. Can you find them?” When you know what you’re looking for, the answers jump out.4

In this case, it strikes me that “meanwhile” is in fact a compound word made up of two parts: “mean” (in the sense of average or middle) and “while” (in the sense of a period of time). So from an etymological perspective, “meanwhile” describes being in the middle of a flow of time. This adds more color to our emerging thesis: In a continuous present, there is little we can do other than react to the world around us.

Furthermore, at the end of the poem, the rhythm of the three “meanwhile” sentences is broken by the entrance of a different compound word: “whoever.” Here, again, there is an etymological suggestion: the self (“who”) in time (“ever”). Now, though, the emphasis is not on your being in the middle of time’s flow; it is on the eternal, fathomless ever. In this way, the poem ultimately transcends the drumbeat of “you” living in the “meanwhile” and reaches a state of peace with existence (“whoever you are”). Or in thematic terms: Simple intuition, repeated over time, yields coherence.

Here’s a more formulaic high school English version of this analysis:

In “Wild Geese,” Mary Oliver’s use of repetition highlights the transformative power of intuition. The poem enters on three sentences all beginning with “you”—the first two in quick succession, the third appearance slightly delayed. Similarly, halfway through the poem, the word “meanwhile” appears three times, with the first two instances close together and the third separated by a few lines. Both of these triplets evoke a sense of radiating outward: first as embodied by the individual (“you”) wandering into the future; then as time itself flowing constantly forward. (Indeed, as a compound word, “meanwhile” can literally be read as “in the mean, or middle, of time.”)

Eventually, the rhythm of “meanwhile” is broken by a new line beginning “Whoever you are”; this is a turn in the poem, which unifies the two strands of repetition preceding it. Like “meanwhile,” the word “whoever” is a compound word whose component parts hold thematic resonance: the emergence of an unbounded self (“who”) through time (“ever”). The ultimate message of this repetition, and its final breakage, is that by “over and over” simply letting the “soft animal of your body / love what it loves,” a sense of purpose and coherence naturally emerges.

A skeptic of the bridge method might point out that it depends on a kind of confirmation bias: We are, after all, deciding in advance what it is we’re trying to prove. But this isn’t just a matter of reverse engineering evidence from a foregone conclusion. The real purpose of the bridge method—and the ladder as well—is to give a bit of structure to the process of idea generation, revealing the natural back-and-forth flow between bottom-up and top-down reasoning; this is raw analysis, before it’s been shaped up into a nice paragraph.

Nor, as nice as it would be, is it possible to avoid squishy, subjective methods like this. This is because in most disciplines, by far the hardest challenge is the one of problem selection or hypothesis formation—not the actual solving. In science class, for example, we are handed chemicals to combine or frogs to dissect; rarely if ever are we taught how the great scientists decided to mix certain reagents or slice certain amphibians in the first place. The ladder and bridge are an attempt to answer that question with a bit more precision than “they were just very observant and thought about it a lot!”5

The great gift of the ladder and the bridge is the realization that in writing, as in life, we are never lost. Fundamentally, there are only three situations we ever might find ourselves in, and each implies an obvious course of action:

If we know what we want to do or say, we simply execute the plan;

if we don’t know what we want to do or say, we start climbing rungs until we get to somewhere interesting;

and if we think we know what we want to do or say, we start working at the problem from either side until the details reveal themselves.

With enough exploration and cognitive flexibility, no starting point is too boring—no two nodes impossible to connect in the vast galaxy of the mind. Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, the world offers itself to your imagination.

To be clear: I’m not saying “liquid” and “solid” are social constructs; of course these states of matter have different physical properties. Rather, I’m saying that, in the same way that “sweet” is a sensory experience of “foods that are high in energy” or “red” is a sensory experience of “light with a longer wavelength,” states of matter are a mental projection of base, external reality—as is all human experience.

Essayist-painter-investor Paul Graham offers a similar analogy:

Usually there are several possible responses to a question, which means you're traversing a tree. But essays are linear, not tree-shaped, which means you have to choose one branch to follow at each point. How do you choose? Usually you should follow whichever offers the greatest combination of generality and novelty. I don't consciously rank branches this way; I just follow whichever seems most exciting…

If you're willing to do a lot of rewriting, you don't have to guess right. You can follow a branch and see how it turns out, and if it isn't good enough, cut it and backtrack. I do this all the time. In this essay I've already cut a 17-paragraph subtree, in addition to countless shorter ones. Maybe I'll reattach it at the end, or boil it down to a footnote, or spin it off as its own essay; we'll see.

To mix metaphors a bit: I’m also reminded of the moment when, digging a tunnel in the sand, you feel your hand connect with someone else’s digging from the other side.

This post is itself an example of the bridge technique in that I selected “Wild Geese” to demonstrate the methods before I had actually worked through analysis that would serve as the post’s primary examples.

Economist David Galenson expands on this point in his book Old Masters and Young Geniuses:

Like the scholar, the modern artist’s goal is to innovate—to create new methods and results that change the work of other practitioners…In most cases important scholarly and artistic innovations come from perceiving a previously unrecognized problem in a novel way, before creating a solution to it. And since both scholarship and art questions are usually more durable than answers, the principle contribution often lies more in recognition and formulation of the problem than in the specific solution offered.

Of course one distinguishing feature between the sciences and humanities is that scientists must actually test the hypotheses formed through intuition or observation; in the humanities, by contrast, work is generally not possible to validate empirically, or if it is, its practitioners lack the skill/motivation to do so.

Thanks to

, who first shared the poem “Wild Geese” with me; and to Eli, who recently sent me this meme reminding me of it.