The Myth of Curriculum (Part 2)

The two axes of instruction

This is the second post in a three-part series. Part 1 can be found here.

It's all a manual that we've been writing, a future instructional guide. / If we skipped ahead to our prefulfilled dreams, we'd be lost without our own advice. -Lucius, “Dusty Trails”

In Part 1 of this series, I described the intrinsic difficulty of teaching complex skills: By its nature, true mastery (i.e., of an art, sport, academic discipline, etc.) cannot be easily distilled.

Still, this is really only a “problem” to the extent that it goes unacknowledged. Taken at face value, all this fact suggests is that students need a basic framework and sufficient motivation to improve on their own. Complex skills may not be teachable—but they are certainly learnable through deliberate practice. In Part 3, I’ll outline a speculative vision of what such a model of instruction looks like.

Before I do, though, we need to take a detour to discuss a paradox in acquiring expertise—a chicken-and-egg feature of understanding. I’ll start with what this feels like for the learner, then give it some more generalizable terminology to describe it.

The Ant and the Canvas

Consider this description of reading from English professor/namesake-of-the-blog, Peter Elbow:

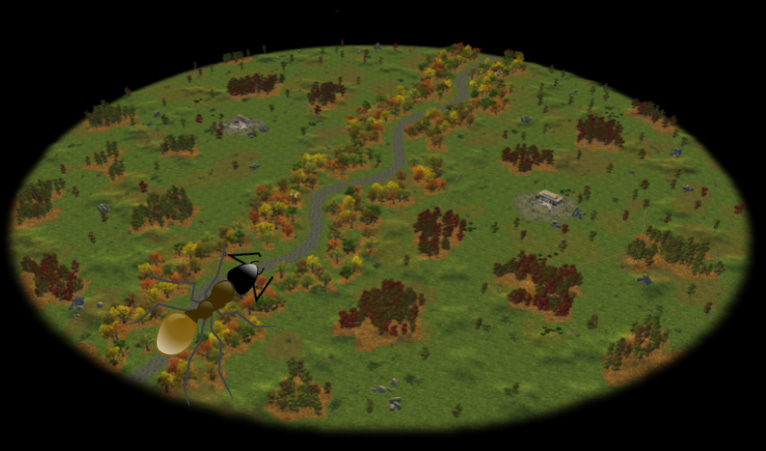

Even though we can look at a page of writing all at once, and even though essays, poems, and books are spatially laid out so all the words sit-there-all-at-once, nevertheless a reader’s experience of writing is not all-at-once. Readers can take in only a relatively few words at a time. Reading is inevitably temporal. When we read a text, we are like ants on a painting: we can crawl all around the canvas but we can never see more than one small part of the painting.

Here, Elbow is concerned primarily with written communication. In fact, learners proceeding through a course usually have it even harder than readers of a new text: While a reader may struggle to see the forest from the trees, they can at least flip around to refer to future or previous sections. By contrast, a student in a typical class must rely solely on prior knowledge (at the start) or recollection (later on) to fit lessons into a larger framework.

So the creator of curricula must balance two competing forces: the goal of presenting the whole canvas, and the reality of the ant’s limited viewpoint.

Of course a teacher can try to show students the “whole canvas,” but in doing so, the picture tends to get grainy and reductive—like viewing The Garden of Earthly Delights on a postage stamp. Zoom out enough, and the image gets simplified to the point of meaninglessness.

Alternatively, students can be allowed to “crawl around,” with the hope that they assemble the complete picture on their own. But what if they miss a crucial section? Or what if the big picture is counterintuitive in some way, or greater than the sum of its parts?

In practice, the best a teacher can do is strike a compromise, toggling between a bird’s-eye and ant’s-eye view of the canvas. Still, this is only an approximation of expert knowledge, which seamlessly integrates both perspectives. Like a muralist working brushstroke by brushstroke to render their grand design, the expert must understand exactly where each detail lies in relation to the whole.

The Circularity of Knowing

The focus of Part 1 was all that experts struggle to explain—but of course there’s a lot experts can explain. In addition to their extensive implicit knowledge, part of what distinguishes experts is indeed explicit concepts and schemas.

In one famous study, for example, experts and novices were asked to sort physics problems into categories; while the pros formed categories based on fundamental laws of physics, the n00bs were much more likely to group the problems according to their surface similarities.

Part of the teacher’s job, then, is to convey the underlying structure of knowledge to the student—to give them the right scaffold on which to build their emerging skills.

This is where we bump up against a catch-22: While a structure is needed to organize new information, there is nothing to organize until you already have all the information. It’s the ant and the canvas all over again. Take a look, for example, at these chapter titles I pulled from a random Quantum Physics Textbook:

Probability and probability amplitudes

Operators, measurement and time evolution

Harmonic oscillators and magnetic fields

Transformations & Observables

Motion in step potentials

Composite systems

Angular Momentum

Hydrogen

Perturbation theory

Helium and the periodic table

Adiabatic principle

Scattering Theory

Assuming no prior specialized knowledge, you probably recognize some of the words here, but their deeper meaning remains a mystery; the actual contents of the chapters—i.e., your real understanding of physics—is nearly as opaque as if you didn’t have the chapter titles at all. The categories can only make sense after you’ve read through the textbook, if then (and presumably then only with the guidance of an actual physics instructor).

So far here, this is just a more concrete restatement of what I described above in metaphorical terms: Experts can sort and place knowledge more effectively on the “canvas”; but they can also work through problems with greater fluency and flexibility, i.e., as “ants”. (As I argued in Part 1, they also probably sense how the overt categories actually blur and interact with each other more than is acknowledged.)

But what should a thoughtful instructor do with this reality? How can we think about the tension in a more systematic way? Here, I think generalizable terms are useful: The top-down, big-picture taxonomy that holds relevant knowledge can be thought of as the vertical axis of instruction; this is the canvas—the table of contents.

By contrast, the ability to work in or with a body of knowledge is the horizontal axis of instruction; this is the ant’s continuous march—the temporal or narrative sequence of learning. Here’s a simplified visualization of this using musical instruments:

These two axes—the vertical and horizontal—exist in unavoidable tension with one another. On the one hand, all new information must be integrated into an existing vertical structure; this is the essence of making meaning. On the other hand, lived experience has an essentially horizontal quality to it: We perceive information—especially new information—not in outline form but more as an endless film or feed; we feel things out with our antennas.

How can this fundamental tension be reconciled? This is the question I’ll tackle in the third and final part of this series.