Guys, I Think I Might Be a Virtue Ethicist?

Amateur moral philosophy devolves into folk psychology

You can admire anyone for being themselves. It’s hard not to when everyone’s so good at it. But when you think of them all together like that, how can you choose? How can you say, “I’d rather be responsible like Misha than irresponsible like Margaux?” Responsibility looks so good on Misha, and irresponsibility looks so good on Margaux. How could I know which would look best on me? -Sheila Heti, How Should a Person Be?

In the study of normative ethics, consequentialism—along with its trolley-obsessed little cousin, utilitarianism—is the branch most closely associated with Effective Altruism. Simply put, this is the view that morality is defined by the real-world impacts of actions. It’s an intuitive and broadly appealing ethical framework.

Following the downfall of “hairy plotter” Sam Bankman-Fried, however, EA has taken some heat for the logical extremes to which it takes consequentialism. In its oldest and least controversial form, EA emphasizes measuring and predicting positive impacts—and surely deserves praise for bringing greater resources to those who need them most; in its most dubious form, EA gravitates to ends-justify-the-means thinking and endorses sketchy bets with high “expected value.” (

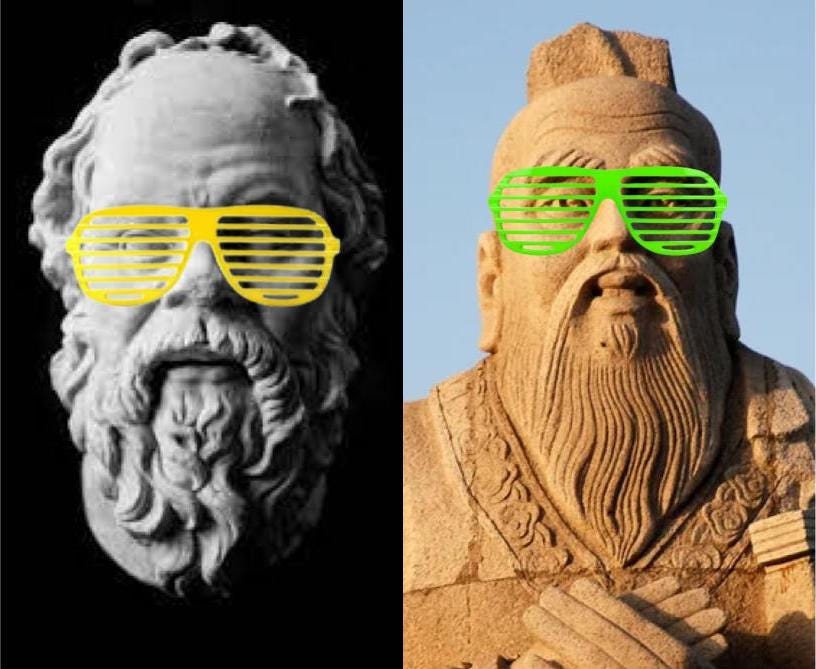

summarizes this critique nicely in his piece EA can’t run from its Frankenstein monster [paywalled]. It’s also worth noting that consequentialism is not the official philosophy of EA but rather a dominant flavor that often seems to run through EA culture and thinking.)That said, when it comes to right and wrong, consequentialism isn’t the only show in town. There’s also deontology—the view that morality is determined by rights or duties. (Think categorical imperative, or divine laws like “Thou shalt not kill.”) And then there’s virtue ethics—the view that morality is determined by the character of the moral actor. (Shoutout to OG virtue ethicist Socrates and my man Confucius.)

I like virtue ethics. I like it not because I think it’s the most likely to reveal absolute Moral Truth™ (of the big three, I think it actually might be the least likely to do that?), but simply because I find it easier to operationalize in day-to-day life. Because the questions “What will the ultimate impact of this action be?” and “What are my rights and duties in this situation?” usually provide a less satisfying answer than the question “What kind of person do I want to be?”

The truth is, most of our everyday ethical dilemmas don’t involve experience machines or organ-harvesting killer surgeons or the creation of 10 billion barely livable lives. Rather, they involve banal judgments like how much to tip our rude but clearly overwhelmed barista, or whether anyone will notice that we used up the last roll of toilet paper. These are dilemmas that could be solved by consequentialism or deontology, of course—but to do so would, I think, elevate them to the status of an ancient Greek melodrama when what we usually need is just a bit of clarity and permission to get on with our lives.

Suppose, for example, that you are a charity director deciding whether to throw an absolute banger of a holiday party. On the one hand, this could be viewed as a frivolous expense not in keeping with the philanthropic mission of your organization. On the other hand: A holistic consequentialist analysis might treat workplace culture as a valid consideration; and a deontologist one might emphasize the director’s duty to support employee wellbeing and retention. Again, the point here is not whether the holiday party itself is right or wrong—it’s that there’s often no obvious way to determine the answer. Ultimate consequences are difficult to predict, and obligations frequently compete with one another.

How does virtue ethics help here? Essentially just by being more straightforward about the fact that the decision is an inherently squishy one. After all, there are many different models of successful leadership, and many possible virtues you might aspire to cultivate as a director. Like consequentialism or deontology, virtue ethics doesn’t automatically reveal a single answer here—but it serves as a reminder that many acceptable answers do exist: They’re all around you, all the time, at work and school and in your home. In other words, while you might not be able to enumerate every conceivable consequence or duty for a given moral act, you can almost certainly think of a few role models whose character you might try to emulate. All you need to do, then, is mentally hold up these possible ideals of yourself—each admirable in their own way—and decide which one you want to take an incremental step toward becoming.

In addition, virtue ethics offers something that consequentialism and deontology can’t easily offer: a nudge toward desirable traits not easily located on the abstract moral landscape. Humor, tidiness, and good conversation, for example, are all qualities I’ve appreciated in my roommates through the years—but is being messy or boring actively immoral? With consequentialism or deontology, I’m not entirely sure how to answer that question; I do feel comfortable, however, in saying they’re decisive virtues.

Of course, “virtues” have to come from somewhere, and I’d concede that consequentialism and deontology might help inform such beliefs. In some contexts, for example, the moral character you’re trying to develop may be a more utilitarian-leaning one. But in other contexts, where the myriad moral and factual unknowns become paralyzing, I find that a focus on other humanistic virtues makes me a more purposeful agent in the world. (To be fair, the opposite hybrid is also possible: A consequentialist or deontologist could argue that virtues matter because, e.g., virtuous individuals are more likely to effect good outcomes. To me, this framing feels clunkier, but maybe it works for some people?)

In truth, the lifelong tension between impact, duties, and self-actualization is never fully resolved. Jeremy Bentham and Immanuel Kant offered their own timeless answers to the riddle, of course—and they were certainly smart fellas. But so did Marge Piercy when she wrote:

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience

And so did Mary Oliver when she asked, famously:

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?