By the time we reach adolescence, most of us learn to filter certain judgments through a private game of translation:

“I don’t know if that school is a great fit for you?” = You’re too dumb to get into Harvard.

“I don’t really see you two as a couple?” = She’s out of your league, dude.

“I don’t know if this is my kind of music?” = Your EP sucks butt.

Usually, the bearers of this bad news have the decency to spare us its most brutal form, but we understand the basic message: We’re not good enough.

And look, I’m not out here to proclaim that status hierarchies don’t exist; clearly, they do—no matter how often we’d like to pretend otherwise. Clearly Harvard confers material advantages that most community colleges do not, and Arby’s is not just a “different style” restaurant than an upscale steakhouse.

But status is not the only factor that predicts happiness and success. It’s not like there’s a single rank-ordering of schools/jobs/content/potential mates to which you rise or fall according to your own smartness/merit/coolness/hotness. Different preferences do, in fact, exist.

I realize this isn’t a groundbreaking epiphany, but it’s something I wish I’d internalized earlier—and something that feels easier than ever to forget in the constant onslaught of likes and shares and “best of” lists. So in the spirit of boosting ideas that everyone already knows, I’d like to say this loud and clear: “Good fit” isn't just a euphemism.

Choose Your Fighter

I know—this narrative sounds like exactly the kind of convenient lie we’d latch onto to help ourselves sleep at night. Sometimes it is. But in my own nascent career, and in working with many young people who are themselves figuring things out, I’ve started to think that fit is underappreciated by far too many of us.

Of course this isn’t surprising, given the nebulousness of “fit” in comparison to the easy answer of rankings and metrics. But what we often fail to consider is that for complex judgments—certainly any judgment as subjective as a rotten tomato or decision to retweet or the caliber of a university—those summary statistics obscure an implicit weighting of many different inputs.

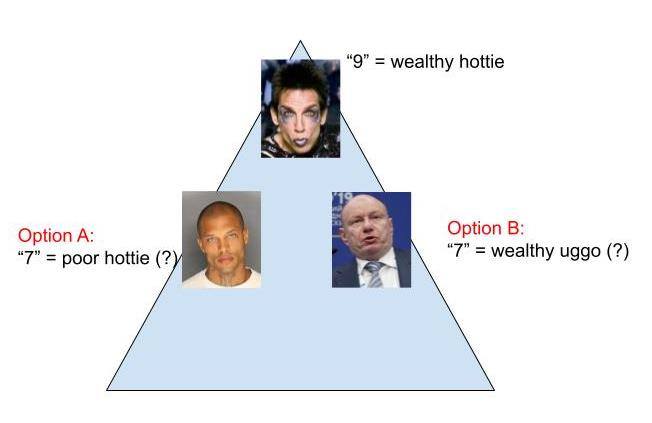

If wealth and physical attractiveness are two desirable traits in a mate, for example, and one potential mate is poor but attractive while another is a wealthy uggo, which one is higher in desirability?

Both options here are “7s”—but the routes by which they arrived at that number are quite different. The “correct choice” depends, of course, on taste. Mayyybe at the tippy top of the pyramid is some theoretical individual who checks every single box; but at every level below that, people are going to check some boxes and not others, in varying proportions. “Good fit” is just another way of saying which boxes are a must-check for you. (And vice versa: what the other party’s must-check boxes are.)

To be fair, sometimes life really will present you with a choice between a 9 and a 7, so to speak: one option that provides all the other has to offer and then some. Should you face such an easy choice, take the 9—what are you, crazy?

But usually you won’t face such easy choices. Usually you’ll have to choose between two ambiguous 7s: decisions in which one option is better than the other in some ways, and worse in others. Because (I’m sorry you had to find out like this…) you yourself are an ambiguous 7, maybe an ambiguous 8 on a good day.

Even when you’re qualified for an opportunity, that is, your unique constellation of (mostly) strengths and (a few) weaknesses will always allow for a subset of situations where someone else would be better. Of course, the same is true of those people/organizations you hope will select you: They’re not perfect, either. To quote psychotherapist Phil Stutz, of Netflix fame, “There's a little turd in every pearl.”

As a general rule, no one person (school, job, etc.) can provide everything; different desirable qualities trade off with each other. Sometimes this is because of randomness (e.g., genetic lotteries) and sometimes it’s because the very trait that makes someone effective has a hidden downside (e.g., Your expertise in quantum mechanics makes it difficult for you to explain quantum mechanics to someone who hasn’t mastered the basics). Sometimes the tradeoffs are not a preordained rule of nature but just a pervasive pattern in how humans operate (e.g., Do you want a small organization with fewer material resources + a stronger sense of community; or a big one with lots of resources where no one knows each other?) We can't eliminate these tradeoffs. We can only choose the ones that make sense to us: the ones that are a good fit.

Why This Matters

We don’t have a ton of control over where we fall on the vertical status axis. Through whatever combination of skill, experience, temperament, biology, socioeconomic status, and the host of factors that dictate our “rank” in a given domain, our choice set is usually fairly proscribed. We can do some things to increase our overall desirability—especially if we focus on the long run; but mostly, we’re working with what we’ve got.

Yet if we focus instead on the horizontal axis—on the differences between options that are available to us, all of which are ambiguous 7s—then we can exercise some agency. Rather than a referendum on our self-worth, the outcome becomes an expression of our values.

And when we find ourselves questioning other people’s choices, this is often a version of the same mistake. We falsely assume that they have the same values that we do, or even confuse our subjective preferences for an objective status hierarchy. As an introvert, for example, I’ve often been amazed that anyone gets genuine enjoyment from “going out.” (This is just a necessary evil we all have to put up with, right??) I have a similarly hard time believing that anyone would voluntarily opt for a plain bagel, or that there are people who actually think Elton John is a superior artist to William “Billy” Joel. But I have it on good authority that these people exist—indeed, that they likely find my perspective just as baffling as I find theirs—and the best I can do is take their word for it.

More broadly, it’s tempting to envy or admire those who achieve whatever it is that we want. It’s tempting to feel smug or sympathetic when they fall short of our goals. But before we take stock of other people’s happiness, we’d do well to understand how they actually define it. Like us, the answer is probably complicated.

TL;DR

Subjectivity is objectively a thing.