Here’s the bad news: You are going to fuck up. At some point in the not-too-distant future, you are going to be stubborn or selfish or senseless in your decision-making. Hell, you might even be fucking up right now by shirking your personal obligations to read a blog post!

But here’s the good news: You can fix these mistakes.

And here’s the really good news: You can fix these mistakes so well that sometimes people will actually like you better than if you had never made them in the first place.

So often when we err, we imagine repair as just a struggle to get back to baseline—to “undo” the damage and raise our standing up to its previous level, if not a hair below. But the truth is there are a range of possible outcomes that can flow out of a failure or transgression—ranging from continued reputational damage, to net neutral impact, to the phenomenon I’m interested in today, “repairadox”: a failure that ultimately leaves the fail-er better off than when they started.

This positive outcome is hardly a universal law, of course. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that most mistakes do NOT have this effect. Still, there are good reasons to believe that repairadoxes really do occur—and probably more often than we think!

From the Armchair

Although it can be easy to forget when we are seeking forgiveness, there are several theoretical mechanisms behind the repairadox that are quite intuitive.

First, in long-lasting relationships (by which I mean not just romantic connections but also platonic, professional, and familial ones), it is practically inevitable that someone will fuck up at some point—the question is just when. For this reason, it makes complete sense to place high value on a person’s capacity to repair mistakes: A willingness to take responsibility and clean up one’s messes is, arguably, a stronger signal of long-term success than is an unrealistic yardstick of perfection. In this sense, the cycle of breakage and repair can be viewed as a tax or short-term cost that helps ensure the long-term health of the relationship.

Second, consider the situation from the perspective of an apology recipient. When we are truly ready to forgive, it often feels quite good to reveal ourselves as chill, merciful, or reassuring—to exercise the better angels of our nature. There’s a kind of potential energy in unresolved conflict, I think, that can lead to moments of unusual closeness upon release: the tenderness of reconciliation.

To be in a position to bring about this state (i.e., to be offered an apology) is to hold a kind of power. Naturally, then, we like people who give us the occasional opportunity to forgive—so long as the offense is not beyond the pale and they don’t abuse the privilege.

(A literal example of this: Victims of domestic violence sometimes point to false hope in their partners’ capacity to change as a reason for staying in relationships. So there’s an especially acute danger in repairadox, I think, when the allure of redemption is exploited by those who are not in fact worthy of being redeemed.)

Finally, it’s often the case that mere contact—even contact based on conflict or disappointment—can raise a person’s esteem. Again, there are limits to this principle, but it’s really just a natural corollary of the familiarity heuristic: the tendency to prefer that which is encountered more frequently. (This bias helps explain everything from why that song you used to hate starts to grow on you the fiftieth time you hear it, to why courting political controversy is an increasingly successful strategy—a fast track to higher name/face recognition.)

As an educator, I’ve certainly found this all-contact-is-good-contact principle to be true. There are B students who quietly drift through a course, demonstrating neither exceptional ability nor cause for alarm; then there are those whose final B represents many ups and downs—through crises of faith or great resistance followed by bursts of creative energy and rapid improvement. Ultimately, these two archetypes of learner may end up in the “same place” gradewise; but I usually develop far greater understanding of, and fondness for, the second kind than the first—simply because I have invested far more time and energy with them.

In fact, I think many of us have people in our lives who we at one point found annoying or abrasive—maybe even still do find annoying or abrasive—but over many years of knowing them have come to feel a certain closeness toward: There is a comfort in the devil we go way back with, even if we don’t enjoy every minute in their company.

We’ve now seen evidence that there are a few plausible mechanisms behind repairadoxes: 1. Repairs themselves are a crucial signal of trust; 2. Forgiveness is, generally speaking, a positive emotion; and 3. Within reason, more contact promotes liking.

What is known about how these theoretical mechanisms play out in the real world?

From the Research

The scholarly literature relevant to repairadox takes two forms: first, research on a phenomenon known as the “Service Recovery Paradox” (SRP), which serves as a particularly clear example of repairadox; second, the study of apologies, which suggests various factors that promote the success of repairs in general.

Let’s take these two buckets one at a time.

The Service Recovery Paradox

The SRP was the original inspiration behind this post. (For the sake of showing you what a clever little boy I am concision and accuracy, I coined the term “repairadox,” which applies to a wider variety of situations.)

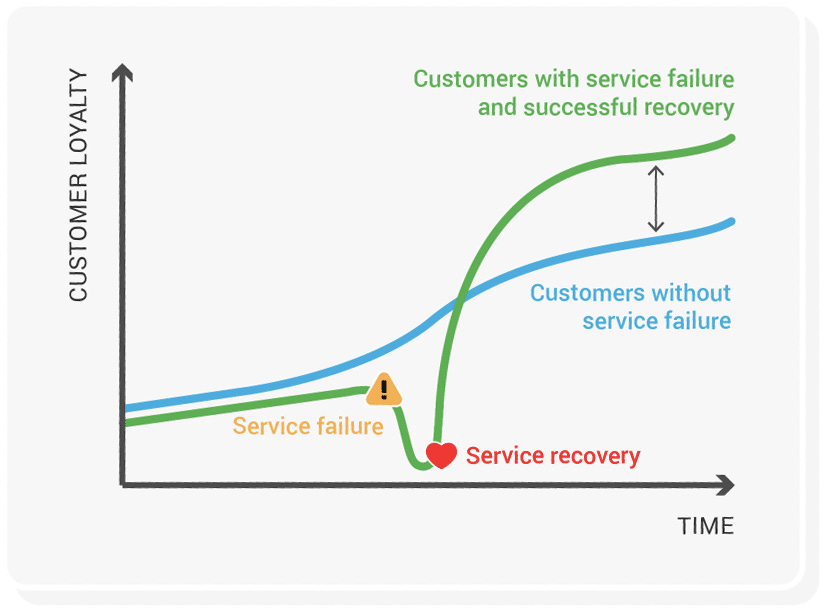

In its original conception, the SRP simply states that businesses which display a strong recovery after a service failure can generate greater customer loyalty than if there had never been an interruption at all:

This, at least, is the promise of the Service Recovery Paradox. Is it actually true?

As with virtually every finding in the social sciences, the answer to that question seems to be: “kind of”/“it depends.”

One 2008 study, for example, found that the SRP was a real but not very robust effect:

Overall, the survey findings support the argument that a service recovery paradox is a rare event, and the hypothesized mean differences are, albeit significant, not very large, which diminishes their managerial relevance to some degree.

Another one from 2007 reached the uninspired conclusion, sure, it can happen—but only if the failure wasn’t really that bad/wasn’t the company’s fault/it was a one-time temporary issue. And a meta-analysis from the same time period found that an SRP in customer satisfaction does not necessarily translate into customer loyalty, and that the SRP was more true in the hospitality industry than the restaurant business. (The authors speculate this is because it’s simply harder to find a new hotel than a new restaurant.)

It’s hardly surprising that the SRP is not a universal consequence of business failures. After all, it’s easy to find examples of botched recoveries, or transgressions so egregious that no amount of apology or compensation can repair the harm. And call me cynical, but I also think that if SRPs were easy to pull off, you’d find more examples of companies trying to deliberately engineer “failures” with miraculous fixes.

For our purposes, though, the overall strength of service recovery is not the point. The most important thing to know about the SRP is simply that it exists—and that there are conditions under which it proves true to a greater or lesser extent.

If customers are capable—at least sometimes—of granting such generosity to faceless corporations, surely they are capable of rewarding individuals they actually know.

Bigger and Better Repairs

As I’ve been reading up on apologies, four factors of repair have emerged in the scholarship.

I. Moral vs. Material Amends

The first crucial factor in apologies goes by a few different names, but the one I like best is what one paper refers to as moral vs. material amends. (Other closely related terms: “acknowledgment” vs. “restitution” or “mortification” vs. “corrective action.”) As anthropologist Hiroshi Wagatsuma and legal scholar Arthur Rosett succinctly put it:

While there are some injuries that cannot be repaired just by saying you are sorry, there are others that can only be repaired by an apology…They include defamation, insult, degradation, loss of status, and the emotional distress and dislocation that accompany conflict.”

A couple anecdotes help illustrate this concept.

Squarely on the “moral amends” side, consider Taylor Swift’s counter-suit of David Mueller—a radio DJ who groped her before a concert—for a total of $1 in damages. Here, Swift was clearly motivated not by a desire for compensation, but simply by a public recognition that what Mueller had done was wrong. The unanimous ruling in her favor sent this message in spite of—or, perhaps, because of—the negligible dollar amount. (Sadly, I’m not aware of Swift ever having received an apology from Mueller…)

On the flip side, consider the haunting “parable of the bicycle,” shared by Reverend Mxolisi Mpambani during South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

There was Tom and there was John. Tom lived opposite John. One day, Tom stole John’s bicycle and every day John saw Tom cycling to school on his bicycle. A year later, Tom walked up to John. He stretched out his hand. “Let’s reconcile and put the past behind us.” John looked at Tom’s hand. “And what about the bicycle?” “No,” said Tom, “I’m not talking about the bicycle. I’m talking about reconciliation.”

In this fictional case—and, by analogy, the case of apartheid—a true recognition of the harm would naturally imply an effort to reverse the material loss that resulted from said harm. So it makes sense to be skeptical of people who profess to feel remorse and then fail to take the obvious corrective steps.

However, it’s worth observing that, almost always, moral amends are the precondition of material amends, and not the other way around. While some might try to argue that restitution implies remorse, I would think that if your goal is an outstanding repair, clear acknowledgment and ownership of responsibility are the first and most important ingredients.

II. Apology Contents and Sequence

A second consideration, explored in this study of celebrity apologies is the contents and sequence of how people say sorry. The key takeaway is that successful apologies are victim-driven, whereas unsuccessful ones are offender-driven, focus on the action or context, or doublecast the apologizer as a simultaneous victim and offender.

Again, a couple examples, as shared in the study. Here’s swimmer Michael Phelps after getting caught with a bong, which Ruane and Cerulo say focuses on Phelp’s actions:

I engaged in behavior which was regrettable and demonstrated bad judgment. I’m 23 years old and despite the successes I’ve had in the pool, I acted in a youthful and inappropriate way, not in a manner people have come to expect from me. For this, I am sorry. I promise my fans and the public it will not happen again.

And here’s pitcher Roger Clemens doublecasting after having an affair:

I know that many people want to know what I have to say about the recent articles in the media. Even though these articles contain many false accusations and mistakes, I need to say that I have made mistakes in my personal life for which I am sorry. I have apologized to my family and apologize to my fans. Like everyone, I have flaws. I have sometimes made choices which have not been right.

To be honest, I have a hard time distinguishing between some of these “bad apology” categories, and could use a few more examples. Still, the takeaway for good apologies seems quite clear: No one gives a shit about the context or motivations behind your mistake—and they don’t even really care about what exactly it is you did. They just care that you understand the harm to the victim.

As a positive example, the authors cite Australian Prime Minister’s 2008 apology to the “Stolen Generation” of indigenous Australians, who were subjected to forced family separation, which starts:

Today we honor the Indigenous peoples of this land, the oldest continuing cultures in human history. We reflect on their past mistreatment. We reflect in particular on the mistreatment of those who were Stolen Generations—this blemished chapter in our national history…

Crucially, Ruane and Cerulo note, the way apologizers begin their apologies taps into cultural scripts that set up expectations about how the statement should end. If a transgressor starts with centering the victim but fails to conclude their apology with a statement of remorse and/or corrective action, it will usually fall flat. Here, they point to ineffective apologies like the one issued by Lebron James after relocating from Cleveland to Miami, which starts:

I knew deep down in my heart, as much as I loved my teammates back in Cleveland and as much as I loved home . . . [victims]

…and ends:

I knew I couldn’t do it by myself ...I apologize for the way it happened. But I knew this opportunity was once in a lifetime. [intentions/needs]

In analyzing the apology, they observe, “Readers are primed for corrective action or remorse—but they do not get it. Instead, the offender leads readers to his own intentions and desires. As a result, bloggers feel less than satisfied with the statement and comment on its ‘unfinished’ nature.”

III. Incentives

A third body of evidence comes from economists like Benjamin Ho, whose research shows that incentives help drive apologies.

One study, for example, looked at the impact of apology laws after medical malpractice. This legislation makes doctors’ apologies inadmissible in court in order to “overcome the physicians’ disinclination to apologize because apologies could invite lawsuits.”

As expected, Ho and Liu found that apology laws expedited the resolution process, reduced the number of lawsuits around minor injuries, and reduced the size of settlements after severe ones. It seems that suing people who admit fault is (surprise!) not that conducive to apologies.

In another experiment, in which apologies were issued in the context of a token-trading game, it was found that apologies were more common early in the game, in longer relationships, and from “good types,” (i.e., those who were, in fact, more likely to return a high fraction of tokens). These results are consistent with a lot of intuitions about apology—some of which have already come up

First, when you don’t know someone that well (“early” in the game, so to speak), your apology carries a stronger signal because the other party doesn’t have as much information about you. Should you err early in a relationship, you have extra incentive to demonstrate that the failure is uncharacteristic.

Similarly, when you know you’ll be interacting with someone again in the future, or there is a higher cost to leaving a relationship, you are more likely to reconcile. (Recall that the Service Recovery Paradox is more likely to occur in the hospitality industry than in the restaurant industry; this is thought to be because there are higher switching costs in the case of the former.)

Finally, apologies are a signal of good character if—or perhaps because—there is a cost associated with them. (In fact, the study charged participants varying amounts of tokens in order to apologize.) In the real world the cost of apology might be material, or it might simply be the humbling nature of the act; regardless, the more generally trustworthy a person is, the higher a price they should be willing to pay to restore that trust.

Why would this be the case? Because apologies are a “cost” trustworthy people won’t need to pay very often, as their record should mostly speak for itself. By contrast, saying sorry is only worth it to an untrustworthy person if doing so is cheap: Transgressions are likely to occur more regularly, so the apology doesn’t “buy” as much lasting goodwill.

IV. Timing

Last but not least, a paper titled, “Better Late than Early” highlights the importance of timing in apologies.

Apologize too early, and the apology recipient may question your sincerity—or simply not be ready to let you back in: Victims need to feel confident that they have been heard and understood before they reconcile with transgressors. (The authors refer to this openness to reconciliation as “ripeness.”)

What is the appropriate interval to wait before apologizing? Frantz and Bennigson are tight-lipped on specific timeframes but speculate that ripeness may observe a “U-shaped function,” such that “extremely early and extremely late apologies are likely to be ineffective.”

In general, of course, people don’t often have a change of heart in a single moment, and are slower to change on the big things. This would seem to counsel (in general; when possible) waiting for at least a separate interaction to apologize, and waiting longer after bigger conflicts. Such delays allow not only for more genuine reflection by the transgressor but also, crucially, for the victim’s perception that the transgressor has had ample opportunity to consider the impact of their actions. Even if we are eager to make the repair and be forgiven, this perception is necessary if the apology is to be accepted.

***To make these four suggestions actionable and easy to use, I am linking a handy supplement here titled The Perfect Repair™.

The Promise of Repairadox

Repairadoxes matter because they encourage prosocial behavior. That is, the promise of social reward helps nudge transgressors away from avoidance, defensiveness, or abdication of responsibility.

To be sure, we already have a number of cultural scripts that speak to the silver linings of mistakes: They can provide “learning” or “experience” or “a good story.” And this is all true! But these are compensatory rather than direct benefits of failure, and they encourage people to simply minimize the fallout and move on. What they miss is that there is actual upside here: an opportunity in the most concrete sense, rather than the vague reassurance of One day, you’ll be grateful this happened…

As with the SRP, we might ask whether too great an emphasis on repairadox creates a perverse incentive: Is there not something wrong—and potentially dangerous—about ultimately rewarding people for their failures? In theory, yes; in practice, thankfully, I think this trick is difficult to pull off repeatedly, and most of us aren’t sociopathic enough to intentionally err just in order to reap reputational benefits through recovery.

Besides, if we don’t give people real credit for fixing their mistakes, what’s the alternative? Just relying on the purity of their conscience? I’m not saying there aren’t morally upstanding people out there who repair harm on their own—I’m just saying social rewards are also powerful and appropriate!

Admittedly, not all mistakes are equally fixable or forgivable, of course. Sometimes, we simply might not care enough about the relationship to invest the time and energy to make amends. Sometimes a half-assed repair, or none at all, is just what the situation calls for.

But on the margins, I think that if we’re debating whether to correct a mistake, it can be more worth it than we think. Specifically, there’s a category of failure people seem inclined to self-flagellate about and not address—mistakes you might call “unforced errors”: We found out we’ve been saying someone’s name wrong for years; we made a tactless comment about someone’s appearance; we used reply all instead of reply. These situations are embarrassing because they feel so careless and easily preventable.

But it is precisely because they are not premeditated that they are so ripe for repairadox. Everyone can relate to having committed these kinds of inadvertent errors, and they tend to be a bigger deal to the “perpetrator” than the “victim.” Whereas the temptation in addressing these (if at all) is to move on quickly and hope everyone forgets, I’d argue there’s often much to be gained by actively revisiting the mistake to offer a sincere, proportionate apology.

Still, I’d have to concede that there are some really big mistakes that are, well, really difficult to come back from: elaborate deceptions, incessant bullying, crimes against humanity—the list goes on. Are there people who are beyond redemption?

I mean, yeah, probably. But at risk of overgeneralization or pollyannaishness: It seems clear that people can come back from a lot more than we might imagine based on a snapshot at their low point.

Consider, for example, the case of Christian Picciolini—a former neonazi who, after renouncing the white power movement at age twenty-two, has spent the past few decades working to deradicalize the kinds of people he used to fraternize with. And let’s not mince words about the harm he caused: Christian smashed Jewish shop windows on the anniversary of Kristallnacht. He beat up a young woman because she “quit a neo-Nazi group and allegedly had black friends.” As he himself is quoted, “There's nothing that I could say or do that can take away the pain that I caused.”

And he may even be right about that—I don’t know! I can’t say how we’d measure the moral impact of the harm he inflicted against the twenty-five years of harm prevention that followed. But that’s not really the question here.

The question is: How do you feel about Christian, knowing his full history?

It might help here to hold Christian up against his imaginary twin, Dustin. Dustin is an Italian-American guy who works at a bank. He prefers to “stay out of politics,” and has neither been a nazi, nor deradicalized any nazis. He has a wife, two kids, and a dog. His friends describe him as “nice.”

For me, when I compare these two versions of Picciolini, the answer is clear: The person I find more interesting, more sympathetic, more desirable to meet, is Christian…and I think I’m not alone in this judgment? After his decades-long atonement, it’s hard not to admire his quest for self-improvement, and believe the sincerity of his commitment to addressing past mistakes. It’s hard not to root for redemption.

So whatever you did, you monster, I’m sure you can come back from it, too.

TL;DR

Under certain conditions, a person who repairs a mistake will be liked more than if they had never made the mistake in the first place.

Thanks to Charlie for edits.