Conscientiousness = Conscientiousness

Sometimes, the key to an open heart is a stick up your butt

One thing I didn’t appreciate when I was younger was the extent to which being a good friend often requires dull, unsexy mental effort—like responding to emails, or setting a reminder on your phone.

This is because it’s difficult to be a good friend if you’re not reliable.

Specifically, prioritizing our near and dear requires maintaining a baseline level of functioning in order to, e.g., keep track of our social calendars, follow through on favors, remember when people’s birthdays are, and so on. At a certain point, it doesn’t matter how sympathetic a listener you are if I can never get a hold of you!

The word that I think best taps into this tension is conscientiousness. Psychologists define conscientiousness as a tendency toward orderliness, rule-following, and meticulousness—in a word: careful. But lay usage, while still honoring this first meaning, also often understands “conscientious” as an outgrowth of “conscience”—in a word: car-ing. (This meaning is probably closer to the personality trait psychologists call agreeableness.)

I would contend that in the long run, careful conscientiousness—let’s call it “type A conscientiousness”—is crucial if we want to achieve caring (“type B”) conscientiousness.

Care to Read More? :D

To be sure, there are all kinds of legitimate reasons someone might be unreliable (mental illness, economic insecurity, etc.). And a person can still be a pleasure to spend time with even if that time is rare or unpredictable. In general, though, I think people underestimate the role of planning/preparation in facilitating both compassion and plain old fun.

I’ve now made this core point a few times a few different ways, so I won’t belabor it any longer—but I do have some related observations, if you’re interested…

First, it seems to me that as we age, type A conscientiousness tends to take on increasing importance in maintaining relationships: With mounting work obligations, medical issues, mouths to feed, etc. etc., organization is a must if we want to have any time left for the people we love.

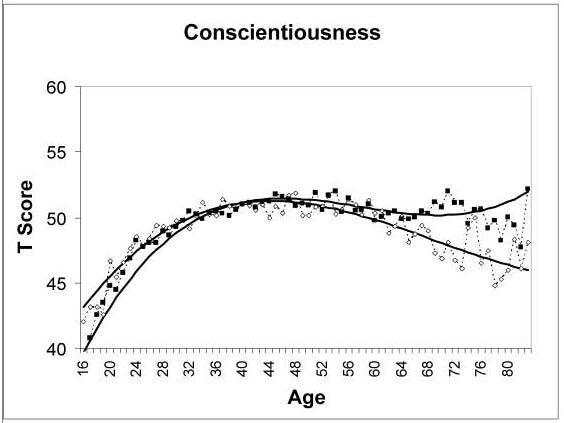

Fortunately, research suggests that type A conscientiousness does in fact tend to increase well into middle age! So this seems like an issue many people figure out how to navigate on their own, in the natural course of human development:

Does type A conscientiousness trade off with type B conscientiousness? (Does, say, being compulsively organized make it more difficult for a person to project basic emotional warmth?)

While I can certainly think of individual people or situations where this might be the case, in general it seems that having your shit together is, actually, totally conducive to being a good person. (Imagine!) As one small piece of evidence in support of this: Observe that agreeableness also increases across the lifespan. (Agreeableness, you’ll recall, is the technical term for “being nice”—and, I think, rough proxy for type B conscientiousness):

Finally, although I’ve focused thus on how type B conscientiousness requires type A conscientiousness, we might also ask whether the opposite is true: How important is it, when executing on objectively nice and supportive behavior, to act/sound nice and supportive?

Honestly, I’m not too sure about this. On the one hand, it’s certainly off-putting when someone treats a virtuous act with a sense of robotic obligation. (Think corporate diversity trainings.) On the other hand, I worry that a really empathetic interpersonal style can sometimes obscure a lack of actual helpfulness? (i.e., As demonstrated by solving problems, showing up, and other type A virtues.)

What’s clear to me, above all else, is that the truly great displays of care depend on both types of conscientiousness: It takes big hugs, and a bit of elbow grease.