This is the first post in a two-part series.

Conventional wisdom about the creative process often boils down to two contradictory pieces of advice.

The first truism is usually framed in terms of grit or depth. To produce exceptional work, the theory goes, you’ve got to show up even when you don’t feel like it: Push yourself. Immerse yourself. Get your butt in the chair and trust that the muse will come.

Yet nearly as often, we are reminded of the importance of taking breaks or managing our energy: It’s a marathon not a sprint. Don’t keep bashing your head against a wall. Let a hundred flowers bloom instead of pouring all your effort into one “masterpiece,” whose ultimate fate is uncertain.

Which of these schools of thought is correct?

As with most cliched advice, there is surely truth to both ideas, and the answer will vary a lot between projects and individuals. I’ve come to develop pretty strong views on how to integrate the two perspectives, however—an approach to making things that is based in personal experience and observation of professionals. I believe that creative processes often—if not always—observe a similar shape; that shape is the S-curve.

What is the S-Curve?

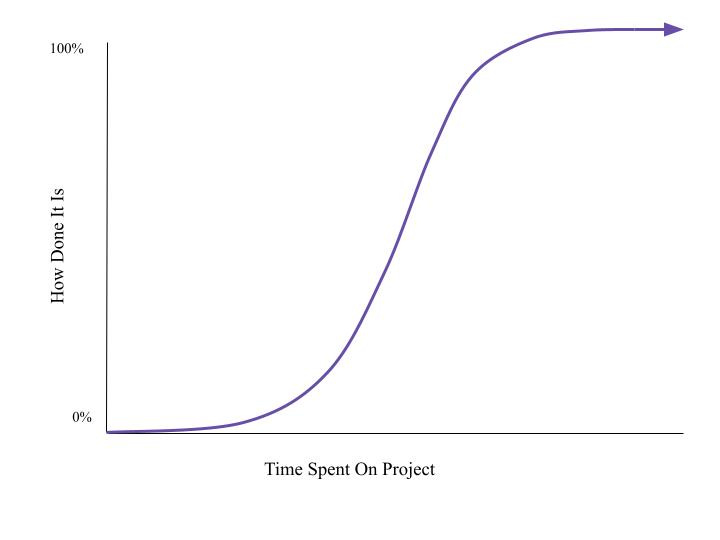

Put simply, the S-curve (or sigmoid function) is a pattern found in nature, computing, and learning: It describes growth that starts off slow, speeds up, then tapers off. This, to me, is often how writing or making something seems to go:

I’ll get into a lot more details on the implications of this graph and why I believe the S-curve is important—but first, an example. Consider this 2.5-minute sequence of Paul McCartney composing “Get Back,” with an ear for how closely it resembles the final version of the song:

(Just an aside to say that while I’m a fan of the Beatles, I’m certainly not taking a stance on whether they’re the Greatest Band Ever™; frankly, I found the Get Back documentary pretty underwhelming. I just think this clip is an excellent microcosm of what it looks like making something from start to finish!)

Returning to S-curves: Notice that although McCartney’s progress on the song is fast by any measure, it is not equally fast throughout the clip. At first, he’s just noodling around; suddenly things seem to cohere very quickly; by the end, he’s mostly just repping the melody he already came up with. This is the generalizable pattern I’m talking about: slow progress, fast progress, slower progress.

Once you start looking for the S-curve, it starts to crop up everywhere:

Art/music/writing/many work products—See McCartney example above, or any creative act that goes through multiple drafts and iterations.

e.g., You brainstorm ideas for a presentation; then create the slides; then spend some time fiddling with the graphics/fonts.

Business/innovation—e.g., You start with very few early adopters as you struggle to introduce people to your new product; suddenly you hit a tipping point and everyone seems to be using your thing; eventually the product becomes ubiquitous and/or you’ve already scooped up almost all the customers you’re going to get.

Learning or skill development—e.g., You start off struggling to just make a sound on your violin/figuring out the best way to grip it; then your movements start becoming more automatized as you learn scales and develop muscle memory; then you focus on more fine-grained musical considerations like tone and embellishments.

Note that while Wikipedia describes the S-curve as the “idealized general form of all learning curves,” it is not the only possible learning curve; you can see with different instruments in the graph (e.g., the kazoo), that musicians’ improvement tends to start very fast and then just plateau. The S-curve is common, but it is not universal.

Career/professional development—e.g., You spend the first 20-30 years of your life in school/trying out different jobs and skills; then you begin to specialize/hone a skill and your career velocity takes off; then you ride it out to retirement in a senior/mentorship role.

Because my orientation is towards writing, I’m going to focus mostly on that in my examples going forward, though I’ll make an effort to also gesture toward other domains and disciplines. That said, I really believe this is a generalizable framework that is relevant to all kinds of creative acts—no matter how seemingly banal or insignificant.

One question that might be asked here is what “done” means on the Y-axis of the graph. In quantifiable terms, you could imagine that, for a piece of writing, this is something like the percentage of words in the final draft that are currently on the page; for business/innovation, you could measure profit or new customers or company valuation; for skill development, you could figure out some indicator of performance like win-loss percentage, or scores by some external evaluator.

As I’ve argued in the past, though, it’s not like creative work is ever done; it just asymptotically approaches doneness. And sadly, achieving success on one dimension often requires sacrificing on another. Even if total perfection were attainable, it could never last. (Think of the athlete who must continue to train in order to maintain skills and fitness; or Shakespeare’s jokes that are no longer funny because the cultural context around them has shifted.)

So I’d suggest that this graph shouldn’t be taken too literally. Creativity is an inherently messy and mysterious act, after all! Rather, I encourage you to treat the S-curve as an idealized or simplified representation of how the creative process often feels.

In the end, it is perhaps just another metaphor—but a really useful one for managing workflow and staying motivated through the act of creation.

Breaking Up the S-Curve

One paradox of creativity: It’s really hard to make something if you don’t yet know what it should look like—but it’s hard to know what it should look like until you actually start making it.

In solving this problem, there are extreme examples in either direction (“plotters” and “pantsers” in writing lingo), but most of us end up kind of zooming in and out between the concrete and the conceptual: We sketch something out in broad strokes, then fill in the details—which in turn, may cause us to reconsider the big picture. This is what I see McCartney doing when he composes “Get Back,” and it creates natural resets in his process. His playing is not really continuous, in other words, but iterative.

To drive this home: You can (theoretically) imagine a world in which McCartney just wrote the complete first 15 seconds of the song—chords, melody, and lyrics—then the next 15 seconds, then the next, until he’d finished it. Of course this would be a strange, arguably superhuman, way to songwrite, and it is decidedly not what he does. Instead, I’d suggest he plays through the entire song every time he stops and restarts, but does so with increasing precision. At first, the “entire song” is just some random chords and humming; he starts again and it converges on a melody; he starts again and sings the near-finished verse and chorus. (I clock the breaks at approximately 0:47, 1:11, and 1:38.)

Can these breaks in the creative process be anticipated? This is far from an exact science, of course, but the S-curve offers some strong indicators of how we might expect things to go, ish.

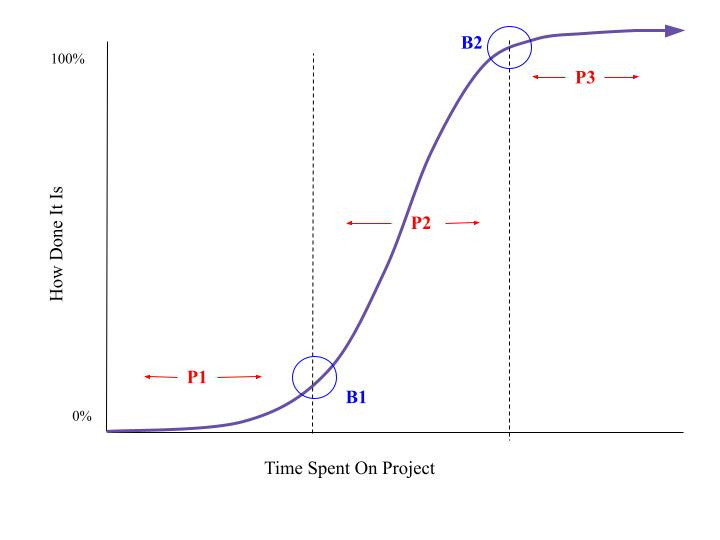

First, it implies two places where we can expect more breaks, or even to build them in: at the beginning of the process, when an idea hasn’t really “caught” yet; and at the end, when progress tapers off.

It also offers a suggestion of when not to take your foot off the gas: in the middle of the process, when improvement is most rapid.

To this, I would add one final prescription—not a rule, by any means, but an approach I’ve often found useful: two places I believe it is especially helpful to step away from a project. Those two places are (wait for it…) at the elbows! (BOOM.)

Phases and Breaks Explained

The “elbows” of the graph are the two points where the rate of progress is changing the fastest: the tipping points or shifts in energy. These points are circled in blue above and labeled B1 and B2, respectively (as in Break 1—or, if you prefer, ’bow 1).

Here I’d like to go into a little more detail on each part of S-curve: What is the purpose of each phase/break—and what does it feel like, phenomenologically?

Phase 1: Exploration

The purpose of Phase 1 is to throw a bunch of shit at the wall and see what sticks.

We have many words for this phase: play, noodling, sketching, brainstorming, napkin math. Some writers call this stage “draft zero”—a product so unshapely it’s not even worthy of the word “first.” You’re not really trying to make anything in Phase 1, other than a mess of ideas you can mine for the few that are worth developing.

Exploration is naturally loopy and relaxed: You have a seed of an idea, but that’s it—don’t force it! Just go about your day and come back to the project when the mood strikes you. The longer your on-ramp, the faster your takeoff velocity.

(As I’ll argue in Part 2, it can also be beneficial during Phase 1 to have multiple projects going at once; if one idea has cooled off, work on the one that’s hot, and return to the first only when you’re ready.)

Break 1: The Momentum Builder

Suddenly, a stroke of inspiration hits you in the shower! Frantically toweling off, trailing water through the living room, you race to your desk/office/studio to get it down. This is an exciting moment because it’s when the project begins to really accelerate and take shape—but be careful: Sometimes that inspiration really is enough to carry you to the end, but other times it’s fleeting. Trust that if it’s a good idea, it’s not going to die on you when you take a break; in fact, it will likely get stronger.

The purpose of Break 1, in other words, is to prepare for the immense outpouring of sustained effort you are about to face in Phase 2.

For a small, fun project (like the McCartney example), we could consider this break optional, or barely visible; the effort isn’t that immense or that sustained, and the creative spark is hot. But the risk, especially with bigger projects, is that you try to get right into Phase 2, and end up just chasing Roadrunner off the cliff. That’s extremely demoralizing. It’s hard to return to a project after you’ve been creatively blocked on it.

So take a break before you do the real work—but keep blowing on the spark. This is an active rest: a time to wool-gather, do research, and get organized. If it’s a good idea, Break 1 can feel a bit like when you learn a new word and start seeing it everywhere. That is, forcing yourself to pause before you build out the project gives it time to marinate. It creates opportunities for you to form unexpected connections and talk to people about it. It gives your unconscious a chance to work on it while you sleep.

Phase 2: Production

This is the hard part—and, when it’s going well, the most fun one: the time when you actually make the thing.

Again, there are lots of words for this phase, some unique to different disciplines and mediums: drafting, composing, takeover, hypergrowth. For me, it often feels a little manic. It’s when the project becomes an obsession—but a good one, like when you can’t stop thinking about a new crush, or can’t stop listening to a new favorite song!

Phase 2 can be a steep climb—but keep going till you reach the top. This is the time to be gritty and get your butt in the chair. The best problems really do require deep, continuous focus to solve, after all; Phase 1 and Break 1 have all been in service of this focus.

Break 2: A Space for Fresh Eyes

When the project has taken on a real shape, and you feel your creative energy starting to dip, you know it’s time to step away again. (Hopefully, this happens at a sensible stopping point—even if the project isn’t very polished yet.)

As with Break 1, there is subjectivity involved in this timing; the general principle is just not to work the thing to death until you’ve made a little space for fresh eyes: your own and someone else’s.

Compared to the first break, this is a more passive rest—at least as it pertains to the project you’ve been working on. (Again, this is a great time to begin working on something else!) Time will naturally give you a different perspective on the work. How much time depends on how big and complicated the project is: Sometimes a day will suffice; sometimes, it takes months or years.

At the end of this break, dust off the project and look over what you have. If it’s complete garbage, then…yikes. Sorry about that! At least you didn’t sink more time into it than you already have?

But there’s probably something there, otherwise you wouldn’t have wanted to make it in the first place. If you feel like the project mostly works, fix the obvious mistakes and consider sending it to someone else for feedback. If you feel like it only kind of works…again, fix the obvious mistakes and consider sending it to someone else for feedback—unless, of course, you know how to fix it yourself.

Phase 3: Editing

The purpose of editing is to make what you already have as good as it can be.

Sometimes, this may require slipping back into production mode. But for writing at least, most of the magic happens in trimming the fat, and moving different pieces around. You’re like a comedian working out their material, or an interior decorator testing out different paint colors now that the house is built. This requires a more critical sensibility and a willingness to reconsider choices.

As with Phase 1, Phase 3 is a more gradual, iterative process. There may be multiple periods of work and rest—tinkering, refining, and revisiting. You may get feedback from one person, incorporate it, then get feedback from someone else who contradicts them. The changes start to feel more and more marginal, until you’re not even sure they matter.

And then eventually, you shrug and say, Fuck it—good enough.

(How do you know what “good enough” is? That could probably be a whole post in and of itself. Various artists have different heuristics for knowing when they’re done, like when all the versions start to feel the same, or when the edits are just making it worse. In the end, I have a suspicion that these are all just abstracted, ritualized versions of Fuck it—good enough.)

Cute Post, Bro—But It’s Not That Simple

I know. Believe me, I know…That’s why there’s a whole part 2 coming to talk about caveats and exceptions, and build out a broader theory of the case!

For now, though, I’d like to offer two closing thoughts on breaking up the S-curve:

First, as I tried to capture in my descriptions above, each stage of creation brings its own joys and stressors: the excitement and uncertainty of a new idea; the immersion and effort of actually making the thing; the bittersweetness of saying goodbye to a beloved project. When your motivation is flagging, it helps to remember that there are challenges in every part of the process. Challenges don’t mean you’re doing something wrong. The S-curve, in short, reminds us that when progress is slow, maybe it’s supposed to be.

Second, an all-important caveat: There are of course no rules for creativity, only guidelines. What works for one person certainly will not work for everyone, and it may not even work for one person tackling different projects. So I hope you’ll simply use whatever’s useful here, and discard the rest.

TL;DR

The creative process—in many domains—often starts slow, speeds up, then tapers off, a pattern known as the S-curve. With this shape in mind, it can be beneficial to take a break after the exploratory phase (“the momentum builder”) and before the editing phase (“a space for fresh eyes”).

In this, the first of two posts, I described the WHAT of breaking up the S-curve; in part 2, I’ll focus more on the WHY and HOW.

Great model. I would add the breaks are really crucial in the creative process. I generate a lot of ideas in the early morning. Taking a break gives a chance for the ideas to percolate (an opportunity to find the gems amidst the ideas which have a lot less resonance after reflection). But multiple breaks are also important during the middle phase. The brain needs recharge time.