This book review was written for the Effective Ideas September blog prize.

In a moment, I’m going to trash on Will MacAskill’s new book, What We Owe the Future—and I’m going to have a lot of nice things to say about it, too, and go down a few weird rabbit holes in the process.

But before I do, I want to try and give you a sense of the ambivalence I felt while reading it, using a made-up ethical system called Circleism. (I got a little carried away with this exercise, so if you want to just get the main thrust, read the first two and last two paragraphs below.):

There are a lot of circles. Circles should not have gaps in them. We could make/repair a lot more circles.

This is the case for Circleism in a nutshell. The premises are simple, and I don’t think they’re particularly controversial. Yet taking them seriously amounts to a moral revolution—one with far-reaching implications for how activists, researchers, policy makers, and indeed all of us should think and act.

Let’s take these premises one at a time:

1. There are a lot of circles

In formal terms, a circle is defined as a series of points in a plane which are all equidistant from a center point. [footnote] More broadly, philosophical and lay understandings suggest that we can think of circles as any object or process that is round. [footnote]

Spheres, for example, fit this definition, although they are three-dimensional rather than two-dimensional. The human head fits this definition, although it is not perfectly round. [footnote] Trees fit this definition, especially if viewed from above.

What about squares? Are squares circles?

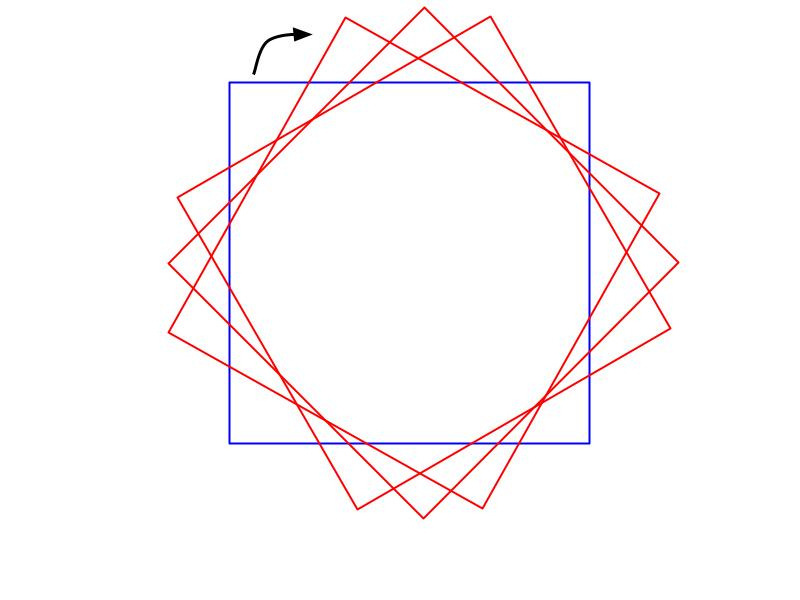

While intuition would suggest that no, squares are not circles, we cannot be certain about this fact. A simple proof demonstrates that under certain conditions, squares can take on properties of circles. Consider that a square can be rotated around a center point to any orientation:

Note, too, that this rotation can be repeated a second or third time:

Repeat this process infinitely many times, and we end up with a shape that, although it does not meet the formal definition of a circle, closely resembles common-sense understandings of that shape:

We have now seen that a wide variety of both theoretical and naturally occurring forms can be categorized as circles. These examples are offered only as a representative sample and are not indicative of the true quantity of circles in the universe. In fact, some researchers have estimated that the total number of circles in existence at any given moment is between 50 billion and 300 trillion. [footnote]

In short, although the true quantity of circles is not something we can quantify with certainty, there are a sufficient number of them, by any reasonable estimate, for them to be worth paying attention to.

2. Circles should not have gaps in them

While we should be cautious about making normative claims of any kind about circles, there is a wide consensus that it is morally good for circles to be unbroken rather than broken. A few different sources of evidence converge on this conclusion.

First, we have survey data going back several decades from people asked to look at images of circles with and without gaps. Overwhelmingly, these surveys show that people prefer unbroken circles (roughly 68% of responses) to broken ones (11% of responses; 21% of respondents have no preference.) [footnote]

Second, we have already identified the head as an unusually circular and important part of the human body. Around the world, social scientists have found strong prohibitions in all cultures against causing gaps in this circle, such as wounds to the skull caused by stabbing and smashing. [footnote] Similar findings hold for other parts of the body, many of which are round. [footnote]

Third, even if the moral status of gaps in circles is uncertain, this does not mean we should avoid taking action on this issue. Because the magnitude of circles in the universe is on the order of billions or trillions, as already discussed, the potential for harm is simply too great to ignore—even if the actual probabilities of circle-related harm remain small.

3. We could make/repair a lot more circles.

Often, the creation of circles is easy and not very costly. For example, here are ten circles:

O O O O O O O O O O

Nor is is difficult to identify gaps in circles in need of repair. Here are four different examples of broken circles:

( ) C @ G

For this reason, the implications of Circleism are wide-ranging. As already argued, Circleism encourages us to take seriously injuries to the human body, particularly the head. It also informs environmental policy, stressing the importance of reducing gaps in the ozone layer. Even the way organizations are run can be designed using Circleist principles, such as the implementation of “circles of trust,” and the construction of buildings that let in more light from the sun, which is a celestial orb.

So what are you waiting for? Get out there and start circling around some important issues!

To be clear, this is a highly exaggerated—and not particularly charitable—parody of the kind of reasoning deployed in What We Owe the Future. Still, it shares a few crucial features with how I felt about the arguments in the book:

First, I more or less agree with the ultimate conclusions of What We Owe the Future.

Second, there are few individual longtermist premises that I object to on their own terms. (And the assumptions and explanations that I do question elicit more of a head scratch than ardent disagreement.)

And yet…

Third, I can’t shake the feeling that despite the appeal of many of its individual components, the framework as a whole ends up seeming a little contrived and ridiculous. (Though this doesn’t mean it can’t still be useful!)

Effective Altruism: An Abridged History, for the Uninitiated

Everyone wants to do good, but many ways of doing good are ineffective. The EA community is focused on finding ways of doing good that actually work.

-effectivealtruism.org (retrieved September 24, 2022)

Since not all readers will be familiar with the history of effective altruism, I wanted to include a quick background/explainer, to be used as needed.

Effective altruism (EA), an outgrowth of the rationalist community influenced by thinkers like Peter Singer, started with a simple question: How good are charities, actually, at enacting good in the world? The unavoidable conclusion: Not that good!

To make this point a little sharper: Historically, a lot of philanthropy has been driven by the beliefs and passions of individual donors/funders, with not enough attention to how successful or cost-effective these charitable efforts actually are. The solution—best embodied by GiveWell—was to get serious about studying and evaluating whether charities actually did what they claimed, and what the price tag was. (It turns out that on a lives-saved-per-dollar metric, this leads you to supporting causes like malaria prevention, reducing malnutrition, and deworming.)

I want to say unequivocally that I think EA is a great development for society. The core insight that some ways of helping the world are demonstrably better than others just seems obviously true and useful! While this core principle arguably biases effective altruism toward causes that are most easy to measure, it’s hard to see how it hasn’t been a hugely positive step for philanthropy as a whole.

Yet even in the movement’s early days, some effective altruists (also, somewhat confusingly, abbreviated EAs) were raising an important and provocative question: Assuming the goal of effecting the most good possible, then you know what would be, like, really really not good? If civilization as we know it was destroyed.

Enter longtermism.

What is Longtermism? (Book Synopsis)

Future people count. There could be a lot of them. We can make their lives go better.

This is the case for longtermism in a nutshell. The premises are simple, and I don’t think they’re particularly controversial. Yet taking them seriously amounts to a moral revolution—one with far-reaching implications for how activists, researchers, policy makers, and indeed all of us should think and act.

-William MacAskill, What We Owe the Future, “Chapter 1: The Case for Longtermism”

What We Owe the Future is a wide-ranging but largely quite accessible book. In broad strokes, it details our general capacity to fuck up the future of humanity, the specific different ways we could fuck up the future of humanity, and the case for why/how the future of humanity can get better.

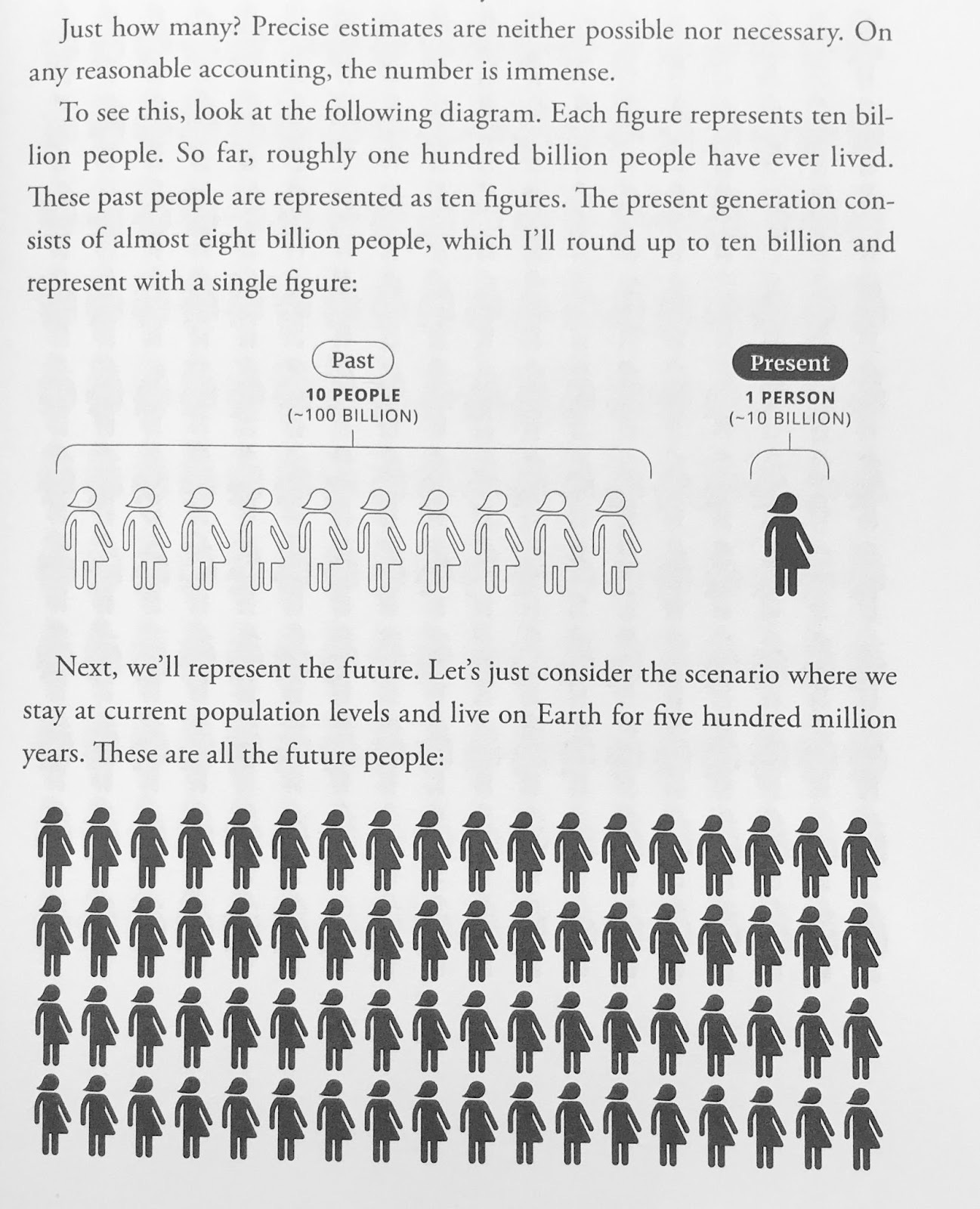

All of these claims rest on the core belief that even by conservative estimates (current population levels, surviving as long as a typical mammalian species), there could be a LOT more humans. To visualize this, MacAskill offers the following diagram—of which I am providing only the first of four people-filled pages:

…before informing us, “I cut the diagram short. The full version would fill twenty thousand pages” (19).

I haven’t checked the math, but it’s certainly striking seeing all the little figures in their little pants-dresses—and, as MacAskill repeatedly emphasizes, we don’t have to be certain about the future to want to avoid really bad outcomes: Even if we think there’s only a small chance this calculation is right, there are sooo many people if it is that we should care about not screwing them over.

To help operationalize, MacAskill has a neat framework for thinking about issues from a longtermist perspective (I’m paraphrasing/simplifying the wording):

Significance—How good or bad is it to do _____ action?

Persistence—How long will the impact of doing _____ last?

Contingency—How likely is it that _____ would happen regardless, (i.e., even if we didn’t do it now)?

Of the three, he believes that persistence is the most important to think about, mostly because of the sheer size of the future: If the impact of an action on humanity is going to last for 500 million years, give or take, it had better be a good one!

Having laid out this rubric, followed by a historical argument for the possibility of moral progress, MacAskill then sets out to show the various ways things could go wrong. These risks include war, climate change, engineered pathogens, economic/technological stagnation, and artificial intelligence that is not aligned with human flourishing. Along the way, he takes some detours to consider questions like, “How likely would civilization be to come back from a catastrophe?” (pretty likely); “Is it morally good to make more humans?” (MacAskill thinks yes); and “Are people getting happier over time?” (probably). Ultimately he concludes that while there is significant uncertainty and many different risks to manage, there is reason for optimism on the whole. Hurray!

(The final chapter, which I’ll speak to more in a moment, offers practical tips for choosing between different longtermist priorities, building an impactful career, and spreading the gospel of effective altruism. Last but not least are the copious acknowledgments, appendices, and endnotes—providing background on collaborators, terminology, equations, sources, etc.)

This, I hope, should give you sufficient context by which to understand the next 5,000 words of critical assessment, hot takes, armchair speculation, and consideration of how physically attractive Will MacAskill is. Buckle up!

Some Praise; Some Criticism; Some Discussion of Killer Robots

I don’t know what it’s going to look like in the end, but I have faith that at the center of the film there’ll be, like, this invisible castle, and each of the scenes will be like throwing sand on the castle. Wherever the sand touches, those different parts of the castle light up. At the end you’ll have a sense of the entire castle. But you never actually see the castle.

-Sheila Heti, How Should a Person Be?

One aspect of this book that makes it genuinely difficult to get a handle on is that its scope is so ambitious, its claims so diverse and numerous, that no one individual could possibly hope to assess them all.

In this spirit, my hope here is simply to throw some sand on the castle, so to speak, and see what it lights up; this will not be an exhaustive assessment of every argument in the book—but it will be enough, I hope, to give you its shape.

On the note of expertise, one aspect of What We Owe the Future I can unequivocally commend is its thoroughness and commitment to truth-seeking. If the endnotes aren’t enough to convince you that MacAskill has done his research, just take a look at how many different collaborators are named in the acknowledgments: Most books don’t have a single chief of staff, let alone three. This epistemic rigor is genuinely impressive, especially considering that most nonfiction books are not fact-checked at all. So I’m glad that if someone is taking on a book like this, they’re taking the responsibility seriously.

If there is any downside to this machine of scholarship, it is that the book can sometimes be stylistically bland in its quest for precision. Even the rare personal anecdotes, such as MacAskill’s account of almost falling to his death through a skylight, are portrayed with an analytical clarity that (for my taste, at least) could benefit from a bit more melodrama:

I was reckless as a teenager and sometimes went “buildering,” also known as urban climbing. Once, coming down from the roof of a hotel in Glasgow, I put my foot on a skylight and fell through. I caught myself at waist height, but the broken glass punctured my side. Luckily, it missed all internal organs. A little deeper, though, and my guts would have popped out violently, and I could easily have died. I still have a scar: three inches long and almost half an inch thick, curved like an earthworm. Dying that evening would have prevented all the rest of my life. My choice to go buildering was therefore an enormously important (and enormously foolish) decision—one of the highest stakes decisions I’ll ever make. (34)

MacAskill’s point is a strong one, and the analogy makes it memorable; but it could be that much more compelling, I think, if it were just ten percent less medical report and ten percent more Holy SHIT, the glass is breaking—am I about to die??? For what a slightly hammed up version of the story might lack in narrative economy or accuracy, I think it would more than make up for in its appeal to a lay audience.

If this is your first foray into effective altruism, I worry the picture I’ve painted thus far might lead you to think that its practitioners, including Will MacAskill, are patronizing, or paternalistic. That is, you might have a caricature of them as moralistic know-it-alls, in the mold of Jordan Peterson or the New Atheists. I want to push back on this view.

To be sure, there is something inherently preachy about telling people to “do good better,” but I really don’t get the sense that effective altruism is interested in dunking on people. My sense (based largely on reading and listening to interviews) is that this is a community of sincere, decent people—and a culture of unusually clear thinking (If you want to just get a flavor for the EA discursive style, I encourage you to listen to a recent interview with MacAskill—of which there are a lot right now—such as this one with NYT columnist Ezra Klein, or this one, from the effective altruist podcast 80,000 Hours.)

MacAskill himself admits to his own early skepticism of longtermism, and flags his continuing uncertainty at multiple points in the book. And in addition to drawing on the knowledge of a huge variety of domain-specific experts, he pulls from a diverse set of philosophical traditions (as far as popular nonfiction goes), including the oral constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy (11), the Hundred Schools of Thought of the Zhou dynasty (75), and the Hadza people of Tanzania (206). While his true ambition does betray itself in his analogizing of longtermism to the feminist and abolitionist movements, it’s a comparison he makes as respectfully and admiringly as possible: Massive cultural shifts in attitude are possible, he wants us to know, and they can have profound moral impact when they do.

Then there’s the conclusions of the book, presented in the final chapter, “What to Do.” These include an exhortation to focus on systemic change rather than “personal behavior or consumption decisions” (231); a suggestion of the kinds of skills people should be building in order to have a high-impact career:

Running organizations

Using political and bureaucratic influence to change the priorities of an organization

Doing conceptual and empirical research on core longtermist topics

Communicating (for example, you might be a great writer or podcast host)

Building new projects from scratch

Building community; bringing together people with different interests and goals. (237)

…and three rules of thumb for way-finding in a highly uncertain future:

[T]hree lessons—take robustly good actions, build up options, and learn more—can help guide us in our attempts to positively influence the long term. First, some actions make the longterm future go better across a wide range of possible scenarios. For example, promoting innovation in clean technology helps keep fossil fuels in the ground, giving us a better chance of recovery after civilizational collapse; it lessens the impact of climate change; it furthers technological progress, reducing the risk of stagnation; and it has major near-term benefits ttoo, reducing the enormous death toll from fossil fuel-based air pollution.

Second, some paths give us many more options than others. This is true on an individual level, where some career paths encourage much more flexible skills and credentials than others. Though I’ve been very lucky in my career, in general, a PhD in economics or statistics leaves open many more opportunities than a philosophy PhD. As I suggested in Chapter 4, keeping options open is important on a societal level, too. Maintaining a diversity of cultures and political systems leaves open more potential trajectories for civilization; the same is true, to an even greater degree, for ensuring that civilization doesn’t end altogether.

Third, we can learn more. As individuals, we can develop a better understanding of the different causes that I’ve discussed in this book and build up knowledge about relevant aspects of the world. Currently there are few attempts to make predictions about political, technological, economic, and social matters more than a decade in advance, and almost no attempts to look more than a hundred years ahead. As a civilization, we can invest resources into doing better—building mirrors that enable us to see, however dimly, into the future. (227)

As I teased at the beginning, I don’t really disagree with any of this. I actually think a lot of it is great advice, especially the careerist stuff about learning and keeping options open. But do I need longtermism to get me there? With very few exceptions, no!

This is what I meant when I said the framework as a whole ends up seeming a little contrived and ridiculous. Just as I don’t need Circleism to tell me it’s bad to destroy the ozone layer or smash people’s heads with a hammer, I don’t need longtermism to tell me that it’s important to “take robustly good actions” or learn about “running organizations.”

I’m hardly the first person to make this point. In a recent Twitter thread, Vox journalist Kelsey Piper put it this way:

And in his review of What We Owe the Future, blogger Scott Alexander writes:

Even though long-termism and near-termism are often allied, [MacAskill] must think that there are some important questions where they disagree, questions simple enough that the average person might encounter them in their ordinary life. Otherwise he wouldn’t have written a book promoting long-termism, or launched a public relations blitz to burn long-termism into the collective consciousness. But I’m not sure what those questions are, and I don’t feel like this book really explained them to me.

In other words, most of the obvious existential threats to humanity (war, pandemics, climate change), are already causes people are pretty concerned about. Admittedly, MacAskill also thinks we should be worried about generally-shitty-but-not-humanity-ending threats, like stagnation and “lock-in” of dystopian values. But presumably most people would agree with that, too, if pressed?

(Counterpoint: Historically, we don’t have a suuuper great track record of dealing with threats that “everyone would agree” are bad, like Covid, or accidentally starting a nuclear war.)

Anyway…

B33P B00P 🤖. 1T 1S R0B0T T1M3 🤖.

Artificial intelligence is probably the most prominent example of a longtermist issue that is not already in mainstream public discourse. But as journalist Matt Yglesias argues, this is fringey not because of longtermism itself; it’s fringey because of a bold empirical claim about when we are likely to get machines with human-level general intelligence:

at the end of the day, the people who work in this field and who call themselves “longtermists” don’t seem to be motivated by any particularly unusual ideas about the long term. And it’s actually quite confusing to portray (as I have previously) their main message in terms of philosophical claims about time horizons. The claim they’re making is that there is a significant chance that current AI research programs will lead to human extinction within the next 20 to 40 years. That’s a very controversial claim to make. But appending “and we should try really hard to stop that” doesn’t make the claim more controversial.

On this particular question of AI, Scott Alexander adds:

Ajeya Cotra’s Biological Anchors report estimates a 10% chance of transformative AI by 2031, and a 50% chance by 2052. Others (eg Eliezer Yudkowsky) think it might happen even sooner.

Let me rephrase this in a deliberately inflammatory way: if you're under ~50, unaligned AI might kill you and everyone you know. Not your great-great-(...)-great-grandchildren in the year 30,000 AD. Not even your children. You and everyone you know. As a pitch to get people to care about something, this is a pretty strong one.

So even AI doesn’t really require a vast future to be worth taking action on. It’s “longtermist” only in the sense that the longtermist community is sounding the alarm on this issue.

Let’s just say that, in practical terms, the real-world impact of What We Owe the Future is to increase the salience of AI safety research; is that a bad outcome?

I don’t feel remotely equipped to evaluate the technical question of whether we are actually close to transformative AI—but I have eyes; and the things computers are capable of now is fucking bonkers, and improving rapidly. Using tools like CHARL-E, you can now generate any image you want from a text prompt, for free. Hell, you even can create a video game using just text prompts:

This seems like big, fundamental step up from computers that are just, say, really good at chess. Like “Will my job be replaced my a robot?” big. So yeah, I’m starting to believe the people who say that we’re on the verge of something as significant as the Industrial Revolution or the internet—something that is going to fundamentally change the economy and the way people live. At the very least, I find these claims credible enough to want us to err on the side of caution and make sure we don’t accidentally turn the world into a paperclip or something similarly catastrophic.

Finally, in this vein, I came across this helpful distinction offered by Eli Lifland:

Let’s disambiguate between 2 connotations of “longtermism”:

A focus on influencing events far in the future.

A focus on the long-term impact of influencing (often near-medium term) events.

Although this distinction was implied in What We Owe the Future, I don’t think I’ve seen it articulated so clearly anywhere else. And while MacAskill does occasionally speculate about #1, the book is really making the (much more reasonable) case for #2—he’s not claiming unusual prophetic powers.

This offers one way to help square the circle of MacAskill’s grand vision with its seemingly obvious conclusions: Longtermists’ beliefs about the world and doing good are (mostly) normal, but a Big Future™ means we should give at least little extra weight to some future-facing moral issues, all else being equal. If we take longtermism as simply a nudge to pay greater attention to those big issues we might naturally notice less (because, say, they develop slowly or have very diffuse impacts), then count me in!

Ok, I think that’s enough sand on the castle for now. We’ll get back to crazy town in a moment, but first…

A Brief Sanity Check

Don't tell me what you value. Show me your budget, and I'll tell you what you value. -Joe Biden

We’ve gone pretty far down the rabbit hole, and we’re about to go there again, so I thought this would be as good a time as any to invoke the patron saint of normies, Joseph Robinette Biden.

Specifically, I think it’s worth stepping back from the big philosophical questions to ask: Looking at the big tent of effective altruism, what kind of resources are actually being devoted to longtermism? This, apparently, is what the picture looks like over the past decade ish:

Looking at this chart, I’ve got to say that my first reaction is, “This seems about right!” Maybe the chickens got a little too much money in 2021 (more on that in a moment…); but still, in 2022, longtermism is having its biggest year yet and is still only getting half of what regular old global health and development is getting ($200 million vs. $400 million). Honestly, if those numbers were $250 million vs. $350 million instead, I don’t think I’d bat an eyelash. If longtermism funding were just crushing near-termism, I’d probably have some reservations about signal-boosting this book—but it’s not, and I don’t imagine it will anytime soon. Plus, as Matt Yglesias observes:

the influx of money for catastrophic risk and EA infrastructure-building has been additive rather than crowding out global health and development funding. So people who worry that the pondering of outlandish-sounding scenarios is coming at the expense of alleviating immediate suffering should find some solace in that.

Agreed. I’d even go a step further and hypothesize that one of the positive effects of longtermism is to shift the Overton window on philanthropy in general—i.e. make OG near-termist effective altruism look more mainstream and appealing by comparison—a big win in my book.

So while all these deep moral questions are fun to debate, keep in mind that it’s not like, in practice, all the money in EA is going to fighting killer robots from the future—far from it!

Mind the Gap

For all E.A.’s aspirations to stringency, its numbers can sometimes seem arbitrarily plastic. MacAskill has a gap between his front teeth, and he told close friends that he was now thinking of getting braces, because studies showed that more “classically” handsome people were more impactful fund-raisers. A friend of his told me, “We were, like, ‘Dude, if you want to have the gap closed, it’s O.K.’ It felt like he had subsumed his own humanity to become a vehicle for the saving of humanity.”

-Gideon Lewis-Kraus, “The Reluctant Prophet of Effective Altruism,” The New Yorker

There’s a strange tradition that writers of New Yorker profiles seem obligated to observe, for reasons which have never been clear to me: At least once per article, the author must insult their subject’s physical appearance with such cutting specificity that it almost doesn’t sound judgmental. (I once saw the singer Caroline Polachek described as “a cyborg who has somehow wandered into a Tolkien novel.”) You can see the version MacAskill gets above.

Although Lewis-Kraus’s formulation is a little ad hominem, I think it does tap into a crucial problem faced by effective altruism, and longtermism in particular: What do you do when your theory of morality is difficult to reconcile with your actual behavior or even just basic moral intuitions?

When these gaps (i.e., between theory and practice) appear, there are generally three ways to reconcile them:

Throw out the theory.

Conclude that your behaviors/intuitions are wrong.

Add all kinds of stipulations and rationalizations to make your theory fit reality.

MacAskill obviously isn’t interested in #1, and although he occasionally resorts to #2 (e.g., he suggests it might be wise to “simply accept the Repugnant Conclusion” (184)), he mostly opts for #3. The upside of this is that it allows him to fit a wider range of issues under the longtermist umbrella; the downside is that it dilutes longtermism and makes it more clunky/complicated.

(Not to belabor the whole tooth gap thing, but in fairness to MacAskill, he does explicitly write, contra The New Yorker’s characterization: “[S]ome effects, though persistent and contingent, just weren’t that significant. I chose not to get braces to close the gap between my two front teeth because at the time I believed that a gap brings good luck. I still have the gap today, but as far as I can tell, it has not significantly affected my life.” (34).

Also, I’d like to go on record and say that the soft smile is 100% working for him—you look great, Will!):

While What We Owe the Future never stoops to the level of using EA principles to justify cosmetic surgery, there are still a few places where we get pretty far from the original premises MacAskill lays out. The most egregious example of this is his foray into animal welfare, which is included as part of an interrogation of what the future holds for “the vast majority of sentient beings on this planet: nonhuman animals.”

Here’s his description of factory-farmed chickens—which, full warning, is pretty horrifying:

Chickens raised for meat, called broiler chickens, are bred to grow so quickly that by the end of their life, 30 percent have moderate to severe walking problems. When they’re big enough to be slaughtered, most broiler chickens are hung upside down by their legs, their heads are passed through electrified water, and then, finally, their throats are cut. Millions of chickens survive this only to finally die when they are submerged in scalding water in a step of the process meant to loosen their feathers.

Egg-laying chickens likely suffer even more, starting the moment they hatch. Male chicks are useless to the egg industry and are therefore “culled” as soon as they’re born. They’re either gassed, ground up, or thrown into the garbage, where they either die of thirst or suffocate to death. But compared to the suffering that awaits female chicks, the culled male chicks may be the fortunate ones. Once grown, many hens are confined to battery cages smaller than a letter-sized piece of paper. Egg-laying hens are prone to peck other hens, which in som cases ends up in cannibalism. To prevent this, a hot blade or infrared light is used to slice off the tips of female chicks’s extremely sensitive beaks. After enduring mutilation as chicks and intense confinement as adults, many egg-laying hens nearing the end of their productive lives are subjected to forced molting: they are starved for two weeks, until they lose a quarter of their body weight, at which point their bodies start another egg-laying cycle. Once they become so unproductive as to be unprofitable, they are gassed or sent to a slaughterhouse. (208-209)

Do I feel good eating eggs and poultry after reading that? No. No I do not! And I’ll definitely admit to avoiding this issue because I’m not yet ready to change my dietary habits, and reading about it makes me feel yucky inside.

But do I really need longtermism to get me to move on this issue? Remind me again how this connects back to “Future people count. There could be a lot of them. We can make their lives go better”? I mean, sure, I was there for every link in the chain of logic, but now it feels like we’re pretty far away from where we started…

Things get even worse when MacAskill tries to operationalize animal welfare by equating moral worth to the number of neurons in an animal’s brain:

To capture the importance of differences in capacity for wellbeing, we could, as a very rough heuristic, weight animals’ interests by the number of neurons they have. The motivating thought behind weighting by neurons is that, since we know that conscious experience of pain is the result of activity in certain neurons in the brain, then it should not matter more that the neurons are divided up among four hundred chickens rather than present in one human. If we do this, then a beetle with 50,000 neurons would have very little capacity for wellbeing; honeybees, with 960,000 neurons would count a little more; chickens, with 200 million neurons, count a lot more, and humans, with over 80 billion neurons, count the most. This gives a very different picture than looking solely at numbers of animals: by neuron count, humans outweigh all farmed animals (including farmed fish) by a factor of thirty to one. (210)

Maybe others feel differently, but this actually makes me care less about animals because it just reeks of rationalization and scientism. Just say we have no clue how to calculate animal suffering! It’s fine, bro!

This commitment to quantification—sometimes at odds with common sense—is one of the elements of effective altruism that really rubs people the wrong way. Although EA claims not to be synonymous with utilitarianism, in practice, a utilitarian logic seems to pervade much of the work the movement does. (In his book review of What We Owe the Future, Erik Hoel critiques this view as treating good and evil like “big mounds of dirt. As a mound-o’-dirt, moral value is totally fungible. It can always be traded and arbitraged, and more is always better.”)

Then again, we’ve already seen that in practice, it’s not like animal welfare is taking up a huge percentage of EA resources. I’m also sympathetic to the fact that at the end of the day, someone has to operationalize the ethics, and the neuron calculation seems like it’s as good napkin math as any—at least as a starting point from which to adjust.

(I’ll also note that EAs often advocate for “worldview diversification”—having different buckets of money with different moral assumptions—to avoid putting all their eggs in one basket, so to speak.)

In any event, the broader point here is that the theory-vs.-practice question is an inherently thorny one, and when this gap is not handled tactfully, it can really turn people off from the movement. In some sense, it’s an impossible puzzle to solve: Throw out your moral theory and you’re left with something like cafeteria religion—picking and choosing your ethics with no underlying principles to guide you; stick too rigidly to your theory and end up with something that contorts or oversimplifies reality. (Which isn’t to say I don’t get the impulse to reduce. Believe me—I get it.)

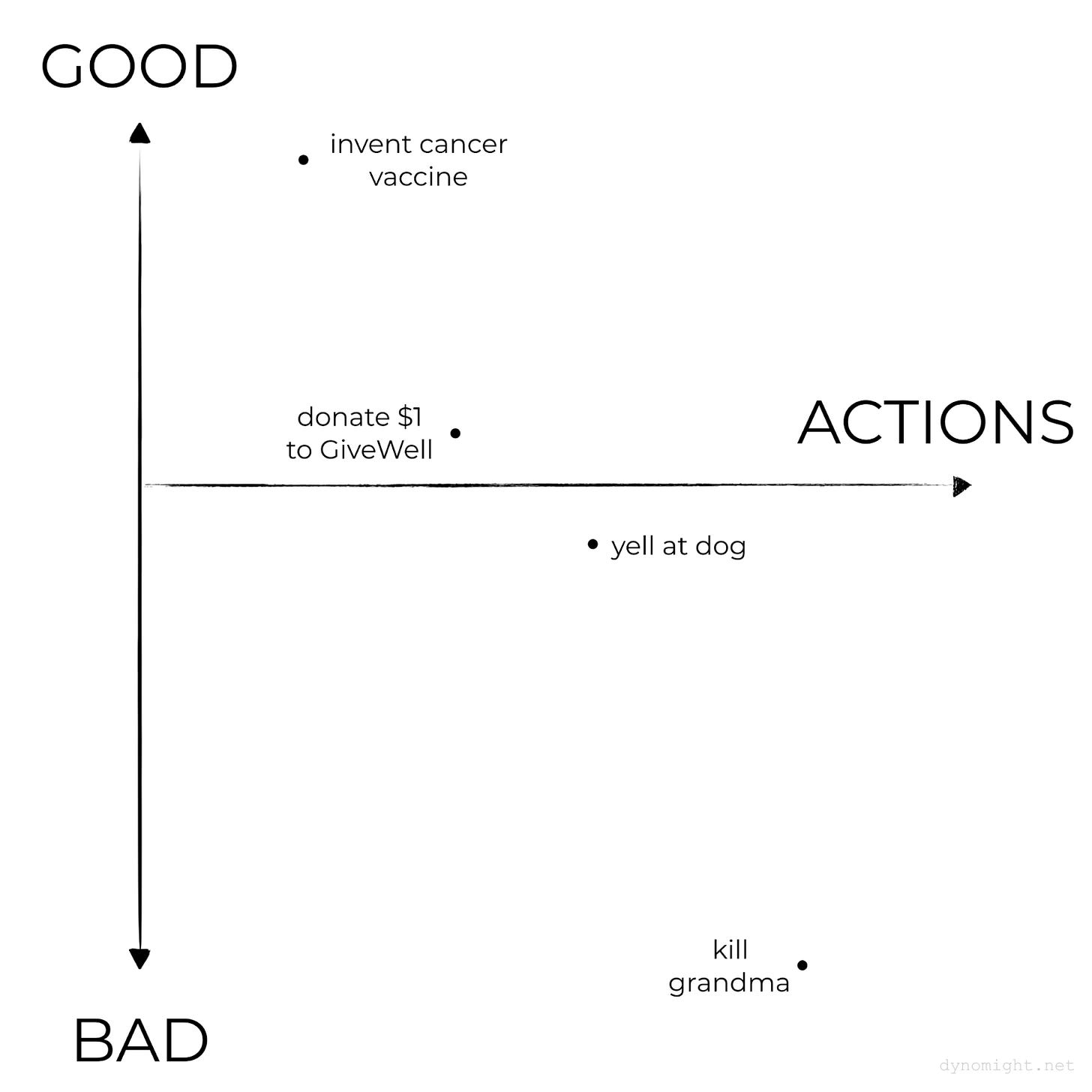

Dynomight has a great visualization of this paradox, which I’m just going to copy + paste wholesale here:

Imagine a space of all possible actions, where nearby actions are similar. And imagine you have a “moral score” for how good you think each action is. Then you can imagine your moral instincts as a graph like this:

Here the x-axis is the space of all possible actions. (This is high-dimensional, but you get the idea.) The y-axis is how good you think each action is.

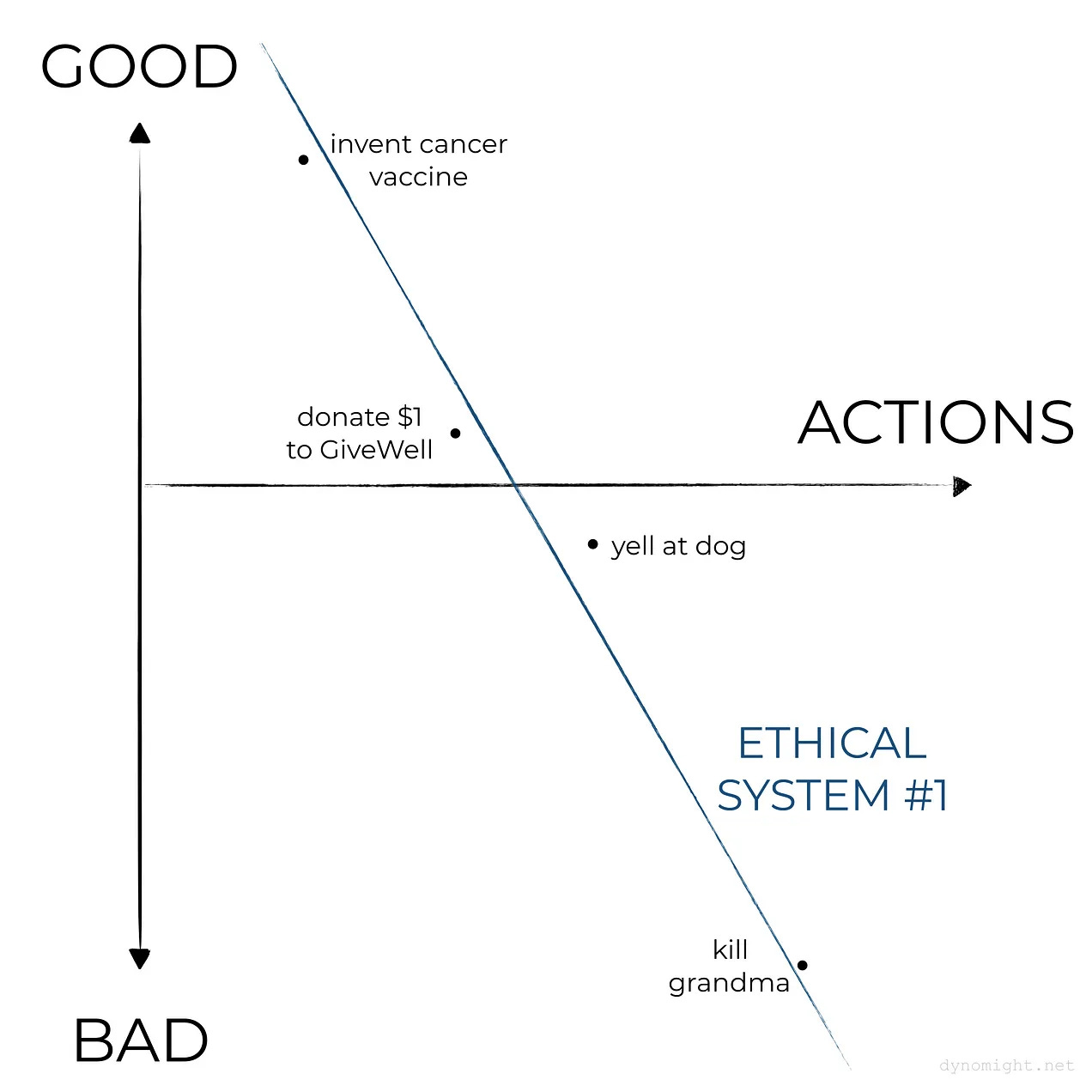

Now, you can picture an ethical system as a function that gives a score to each possible action. Here’s one system:

Here’s another one:

Notice something: Even though ETHICAL SYSTEM #2 fits your moral instincts a bit better, it might not seem quite as trustworthy—it’s too wiggly.

Naturally, it’s inevitable that people will point out the places where a theory breaks down, but if MacAskill makes a strategic blunder in his book, I think it’s in steering toward these places too eagerly. Then, having drawn our attention to the gaps between what a theoretical longtermism implies and what feels right in practice, he makes his theory ~wiggly~ to compensate. This is a shame, because the core case on the big existential-risk issues is pretty compelling!

Coda: Longtermists Without Longtermism?

[A]ccounts of the Mormons—accounts of the people rather than the articles of their strange faith—have often emphasized their cheerful virtue, the upright and yet often relaxed, pragmatic goodness of its adherents, their ability to hold together families and raise decent children and provide the consolations of community in the confusing modern world more successfully than many others. These accounts often pass over in discreet silence the sometimes embarrassing tenets of faith that, especially if one were Mormon, might have been thought an inestimably important part of making that moral success possible. If opponents of Mormonism have often asked, “Can’t we stop the Mormons from being Mormon?”, ostensible admirers of Mormons as people have often asked, at least by implication, “Can’t we have Mormons—but without Mormonism?”

-Kenneth Anderson, “ ‘A Peculiar People’: The Mystical and Pragmatic Appeal of Mormonism,” L.A. Times

As I’ve been wading into these debates about morality, near-termism, and longtermism, I’ve found it helpful to think about some of the rifts as being a difference in temperament or affinity for certain ways of thinking, rather than purely ideological ones. That is, it can be illuminating to set aside the question of whether MacAskill is right or wrong about longtermism and just think of him as someone who really enjoys nerding out over moral philosophy and is unusually talented at it. This is a point Ajeya Cotra makes in her interview on the 80,000 Hours podcast:

So, you can think about the longtermist team as trying to be the best utilitarian philosophers they can be, and trying to philosophy their way into the best goals, and win that way. Where at least moderately good execution on these goals that were identified as good (with a lot of philosophical work) is the bet they’re making, the way they’re trying to win and make their mark on the world. And then the near-termist team is trying to be the best utilitarian economists they can be, trying to be rigorous, and empirical, and quantitative, and smart. And trying to moneyball regular philanthropy, sort of. And they see their competitive advantage as being the economist-y thinking as opposed to the philosopher-y thinking.

And so when the philosopher takes you to a very weird unintuitive place—and, furthermore, wants you to give up all of the other goals that on other ways of thinking about the world that aren’t philosophical seem like they’re worth pursuing—they’re just like, stop… I sometimes think of it as a train going to crazy town, and the near-termist side is like, I’m going to get off the train before we get to the point where all we’re focusing on is existential risk because of the astronomical waste argument. And then the longtermist side stays on the train, and there may be further stops.

This point about getting off the train to crazy town more or less sums up my main critique of the book…Or maybe it’s that I’m actually open to visiting crazy town, at least a bit, but the wild route MacAskill takes to get there is making me trainsick? (Sort of like, Ok, FINE—you can do some AI safety research. I don’t need all the stats and diagrams, just do it!)

In any event, I’ve already spoken admirably of the effective altruist culture in general, and many of these virtues are especially true of longtermists: epistemic humility, a penchant for abstract reasoning, and a dogged determination to act in humanity’s best interests. And I think longtermist causes probably do add a needed counterbalance to other forms of doing good. (Apocalypse or dystopia = bad!) So the main question I’m left with after reading What We Owe the Future is: Can society adopt these virtues without assuming the cumbersome ideological apparatus around it? Can we have longtermists without longtermism?

Sadly I suspect the answer is no. But this isn’t because longtermist culture/behavior follows inevitably from first principles of longtermism. Rather, longtermists need longtermism for the same reason that this book review “needed” to start with a satirical manifesto: They’re drawn to it like a moth to a fucking flame. In other words, anyone who is good at longtermist-style thinking, who acts in future-conscious ways and devotes significant resources to existential risks, is almost certainly going to be the kind of person who can’t resist building out an elaborate philosophical framework around their actions.

As for me, I’m not sure where I fall on the near-termist vs. longtermist personality spectrum—presumably somewhere in the middle, since I still feel pretty ambivalent?

So for now, I’ll be hanging onto my core insights from What We Owe the Future, while keeping a respectful distance from the circle jerk.

TL;DR

What We Owe the Future is an elaborate, arguably excessive, philosophical justification for some ideas that are actually very sensible: Let’s try not to kill future humans or irreversibly ruin their lives.

Personally, I’d hope for a collective shift toward the cognitive style and some of the key issues raised in the book without such an emphasis on the Big Ideas—but I’m not sure it’s possible to get one without the other.