Some books change you by holding your hand through a series of increasingly complex logical leaps, building up an elaborate new system of knowledge. Others simply articulate a truth you always felt deep in your bones, but had never before put into words. For me, Annie Murphy Paul’s The Extended Mind was the latter.

Paul starts with a straightforward premise: The mind is not akin to a computer—to cite one of our most common cultural metaphors for it—but a more flexible, expansive entity that extends out into the world. Instead of a machine, she suggests, the brain is like a “nest-building bird” (viii). Paul explains:

For one thing: thought happens not only inside the skull but out in the world, too; it’s an act of continuous assembly and reassembly that draws on resources external to the brain. For another: the kinds of materials available to “think with” affect the nature and quality of the thought that can be produced. And last: the capacity to think well—that is, to be intelligent—is not a fixed property of the individual but rather a shifting state that is dependent on access to extra-neural resources and the knowledge of how to use them.” (11)

A moment’s reflection reveals that there is much truth to this claim. As Paul argues, “while a laptop works the same way whether it’s being used at the office or while we’re sitting in a park, the brain is deeply affected by the setting in which it operates” (92). Computers are clearly an imperfect—or at least incomplete—model for the mind.

But if the mind is not a sort of machine, if it is more like a “magpie” as Paul claims, what exactly does that mean? How, in fact, does the mind work, and how can we apply this knowledge to our lives? These are the key questions The Extended Mind sets out to answer.

Paul Builds Her Case

The Extended Mind is divided into thirds—one on embodied cognition, one on situated cognition, and one on social cognition—each of which is itself divided into three subsections.

Arguably, this neat threes-within-three structure imposes some artificial constraint on ideas that might otherwise bleed together or cleave apart. But the buckets generally do a good job of holding all the information, and are nothing if not clear. In the spirit of the book’s thesis, I was inspired to map out a kind of visual summary of all this:

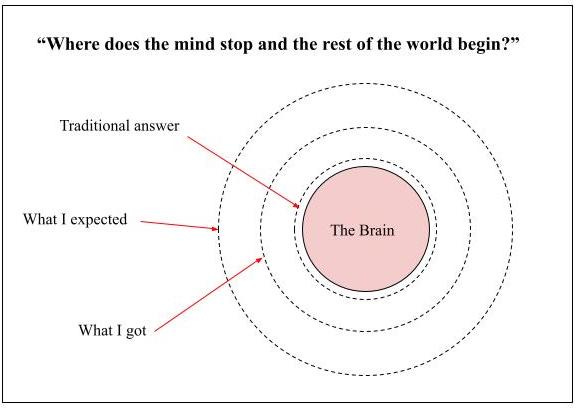

“The Extended Mind” is, in fact, a concept first proposed by philosopher Andy Clark, who coined the phrase in his 1998 paper by the same name, and is cited frequently throughout Paul’s work. This paper sets out to answer a surprisingly tricky philosophical question, which I’ll return to later on: Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin?

(Somehow, I only realized about halfway through writing this that Andy Clark is also the author of Surfing Uncertainty, the subject of one of my all-time favorite book reviews. The writer of that review notes that Clark’s own latest book “isn’t easy reading” and contains “long digressions about various esoteric philosophy-of-cognitive-science debates”—neither of which are charges I would level against The Extended Mind. Paul is clearly very knowledgeable about her subject matter, but it’s evident she cares about making her writing comprehensible for a nonacademic audience, and is especially interested in the practical considerations of her work.)

Like any book laying out a grand theory, The Extended Mind lives and dies by its examples—and Paul’s are without a doubt extraordinary. Although I have some quibbles with how she frames some of this evidence, and believe the conclusions she draws are too strong in a few cases, the book is surely still worth reading for the sheer breadth and intrigue of the research she presents. Some of my favorite examples below, with original papers linked (I’ve skimmed a couple of these but am otherwise assuming she’s summarized them accurately):

From “Thinking with Our Bodies”…

In an experiment requiring subject to flip cards with different monetary rewards and penalties, people’s “skin conductance began to spike when they contemplated clicking on the bad decks” (two were stacked against them); even though it took people another forty or so turns to express this knowledge consciously, participants began gravitating more and more toward the favorable decks (26).

Radiologists improved from 85% to 99% diagnostic accuracy when walking on a treadmill (44).

Doodling improved retention on a boring listening task by 29% (49).

In classic Piagetian conservation tasks, children display emerging understanding through gesture some 40% of the time (75).

(Paul describes: “The girl is shown a tall, skinny glass full of water, the contents of which are then poured into a short, wide glass. Asked whether the amount of water remains the same, the girl answers no—but at the same time, her hands are making a cupping motion, indicating that she’s beginning to understand that the wider shape of the second glass accounts for…the same amount of water.”)

From “Thinking with Our Surroundings”…

“A twenty-minute walk in a park improved children’s concentration and impulse control as much as a dose of an ADHD drug like Ritalin” (96).

“[Medical] patients who occupied rooms with a view of trees required fewer painkillers, experienced fewer complications, and had shorter hospital stays than patients whose rooms looked out on a brick wall” (102).

When negotiating in their own space, hosts claimed 60-160% more value than visitors (126).

In one study, subjects completed basic visualization tasks ten times as fast using a super-sized computer display relative to a smaller screen (148); in another, multiple monitors improved retention by 56% relative to a single screen (149).

From “Thinking with Our Relationships”…

In a computer science course, shifting from a lecture model to a small-group tutoring model reduced the fail rate from as high as 60% to 10% (164).

Trauma surgeons asked to explain how they perform an operation “neglected to cite nearly 70 percent of the actions they performed during the procedure” (181)

(Interpretation: “Experts are able to articulate only about 30 percent of what they know.”)

Performance on the classic Wason Selection Task improves from 10% to 75% when it requires social reasoning vs. pure logical reasoning (193).

Original task: “Take a look at the cards shown here. Each card has a vowel and a consonant on one side and an even or an odd number on the other. Which card or cards must be turned over in order to determine whether it is true that If a card has a vowel on one side, it has an even number on the other?” [Visible card faces = E; K; 3; 6]

Social version: “You are serving at a bar and have to enforce the rule that if a person is drinking beer, they must be 21 years of age or older. The four cards shown here have information about people sitting at a table. One side of the card tells you what a person is drinking, and the other side tells you their age. Which card or cards must you turn over to see if the rule is being broken?” [card faces = over 21; under 21; alcoholic beverage; nonalcoholic beverage]

For athletes and dancers, “moving in unison increases endurance and reduces the perception of physical pain” (218).

I was impressed, too, by how persuasive much of the book’s imaginative and anecdotal evidence—some of it, frankly, even more so than the empirical research. Paul introduces a number of exemplary mind-extenders, for example (Daniel Kahneman, Jackson Pollock, Haruki Murakami), and describes how their seminal work was less “brain-bound” than we might imagine. For me, the most intriguing of these individual examples were a few first-hand descriptions of scientific discovery—here’s how Paul recounts Einstein coming up with relativity:

The world’s most famous physicist, Albert Einstein, reportedly imagined himself riding on a beam of light while developing his theory of relativity. “No scientist thinks in equations,” Einstein once claimed. Rather, he remarked, the elements of his own thought were “visual” and even “muscular” in nature. (61)

And here’s a similar account by Nobel-winning geneticist Barbara McClintock, on looking at corn plant chromosomes through a microscope:

When I was really working with them I wasn’t outside, I was down there. I was part of the system. I was right down there with them, and everything got big. I was even able to see the internal parts of the chromosomes—actually everything was there. It surprised me because I actually felt as if I were right down there and these were my friends. (61)

What strikes me about these examples is how unscientific—even mystical—they sound. Obviously, hunches and roleplay are no substitute for the actual collection of data; I just thought there was something wonderful and kind of telling about the idea of Nobel Prize winners basically method-acting their way into insights.

It’s not like the importance of scientific intuition is a trivial matter, either. In the words of Erick Greene—an ecology/evolutionary biology professor Paul quotes in the book: “One of the hardest parts of science is coming up with new questions. Where do fresh new ideas come from? Careful observations of nature are a great place to start” (153). Maybe this is a common perspective among scientists—but from the outside, it seemed to me like a subtle, underappreciated aspect of how the actual production of knowledge occurs.

In this vein, Paul also builds up a bank of mind-extension vocabulary throughout the book—a useful and intuitive language for discussing learning/knowledge work. Here, again, are some of my favorite examples, with the originator of the phrase indicated when relevant:

On the notion that our brains evolved for, and benefit from, movement of the body: “mind on the hoof” (47; Andy Clark)

On the use of gestures to bolster comprehension and help crystallize understanding: “mental hooks” (84) and “virtual diagrams” (76; Barbara Tversky)

On the kind of diffuse, restorative attention evoked by nature: “soft fascination” (97; William James) or “soft gazing” (97; a tai chi term)

On generic, nondescript buildings: “the cognitive deficiency of non-places” (137; Richard Coyne)

On creators discovering new ideas in things they’ve already made: “the backtalk of self-generated sketches” (155; Gabriela Goldschmidt)

On the mutual benefits of the tutor-tutee relationship: “cognitive apprenticeship” (164; Allan Collins) and “cascading mentorship” (198)

On the loss of ego associated with synchronous movement: “social eddy” (218; Kerry L. Marsh)

On the methods/processes involved in collaboration: “error pruning” (233), “shared artifacts” (233; Gary and Judith Olson), and “transactive memory” (236)

For me, though, the thing that really made me feel like Paul was onto something were a few hypotheticals/mini-demonstrations of the power of externalization. Three examples come to mind:

First, consider the way people write down multiple spellings of a word to see which “looks right,” or rearrange scrabble tiles to come up with new letter combinations. (Check and check.)

Second, consider: “when you step into your shower at home, how do you turn on the hot water?” (59) (Personally, I find this impossible to do without simulating the motion in my head, and it’s made much easier if I mime it.)

Third, my favorite little philosophy-of-mind nugget in the entire book:

Picture a tiger, suggests philosopher Daniel Dennett in a classic thought experiment; imagine in detail its eyes, its nose, its paws, its tail. Following a few moments of conjuring, we may feel we’ve summoned up a fairly complete image. Now, says Dennett, answer this question: How many stripes does the tiger have? Suddenly the mental picture that had seemed so solid becomes maddeningly slippery. If we had drawn the tiger on paper, of course, counting its stripes would be a straightforward task. (153)

If these last three examples don’t convince you that the mind is, in a very real sense, extendable, I don’t know what will.

A Brief Rant About Framing

My only overarching critique of the book: As I was reading, I couldn’t help but think that mind extension isn’t quite the right phrase to encompass the various phenomena Paul describes. It’s not as if we’re able to literally merge with some external neural network, after all, like how in (the movie) Avatar, the blue alien people are able to plug into their tree god or (I am so sorry…) do that thing with their hair tentacles.

Instead, my main takeaway from the book is that our minds aren’t so much reaching out as they are pulling in outside/less centralized resources. (The Acquisitive Mind? The Extractive Mind?) Obviously this framing isn’t quite as provocative as the original title, but I don’t think it detracts from any of the evidence Paul lays out. In fact, I’d argue it’s much more consistent with Paul’s own brain-as-magpie analogy than “extended” is.

Maybe this is a distinction without a difference, or I’m just straw-manning Paul’s argument, but it tripped me up in places. In “Thinking with Our Sensations” [emphasis mine], for example, the implication seemed to be that when we’re aware of our heartbeat (a common measure of interoception), our heart is literally doing the thinking. I just have a really hard time believing that.

By contrast, I’m quite interested in the (slightly weaker) claim that cognition works better when it utilizes sense data and inputs from the peripheral nervous system—or something like that. In short, I think there’s a bit of motte-and-bailey action going on here, but the motte is still really cool and worthy of attention:

If anyone is guilty of overextending the concept of extending, it’s Andy Clark, the coiner of the term. In his OG 1998 paper, Clark writes, “the human organism is linked with an external entity in a two-way interaction, creating a coupled system that can be seen as a cognitive system in its own right.” But is a “coupled…cognitive system” the same thing as a mind? I guess we can define words however we want, but to me this feels like referring to an individual bank account as a “financial system” because money goes in and out of it, or to a person as a “social system” because they interact with the rest of society. (Clark actually goes there, too, speculating about an “extended self” at the end of the paper.)

In a thought experiment—about a notebook-carrying amnesic and a neurotypical person who occasionally doesn’t have access to their own memories (as in sleep or heavy intoxication)—Clark argues that there is no meaningful difference between an internal and reliable external process for retrieving information. To insist on this distinction, he argues, would result in an “unnatural” way of speaking and “complicates the explanation unnecessarily.”

So basically…the mind is in fact extended because it would sound awkward to describe it more accurately? Again, I’m skeptical. If we want to use “thinking” as a shorthand for “external processes relevant to cognition” (the same way we might say that electrons “like” or “want” certain configurations; or that the owner of a house “built” it, rather than, e.g., “hired a bunch of construction workers and paid for all the materials that went into making it”), then fine! This seems reasonable in everyday conversation. But if we’re trying to describe what’s literally going on with the brain and study it scientifically, I’m having a hard time getting behind “extended.”

Paul—whether because she’s uninterested, is writing for a nonacademic audience, or has made the (probably correct) assessment that it’s just not worth getting into all this—mostly avoids parsing definitions. For her “the extended mind” is more of a Christmas tree on which to hang her evidence, ornaments whose coherence stems more from general patterns that can be observed in the mind’s functioning than rigorous philosophical debate.

Or as writer Larissa MacFarquhar observes in her profile of Andy Clark: “this isn’t really a factual claim [about the mind]; clearly, you can make a case either way. No, it’s more a way of thinking about what sort of creature a human is.”

Why/How Do Mental Extensions Actually Work?

As someone who has spent most of his career in the high school classroom, I was naturally drawn to the pedagogical implications in Paul’s work, both implicit and explicit. Effective instruction is notoriously difficult to measure—let alone replicate—and for good reason: The classroom is a mess of weird incentives, ranging abilities, and raging hormones. If you think of your own favorite teachers growing up, you’ll probably observe that each of them was great in a fairly distinct way; that is, they found a unique set of solutions for working through these competing considerations. (This isn’t to say there isn’t any generalizable advice for educators, of course.)

Unfortunately the messiness of the classroom means that while The Extended Mind raises a number of valuable pedagogical questions, actual best practices are still sometimes elusive. In part, this is because—and here we reach a really important issue that generalizes well beyond the classroom—prioritizing one kind of mental extension sometimes requires sacrificing another, or at least not optimizing for it.

In his interview with Paul about the book, for example, journalist Ezra Klein raises the following contradiction:

The locus of economic and to some degree idea generation is going more and more towards agglomerations of people. It’s not like per person rural areas are wildly more productive than urban ones. And it seems to me there is some tension between how clear the research seems to be that nature is good for our minds and how clear the actual patterns of economic and creative growth are that being around a lot of other people in a concrete jungle is good for idea generation and human organization and economic organization. How do you reconcile those?

Paul counters that “even within cities and suburbs, there’s a really unequal distribution of access to green areas and green spaces”—which is fair enough. But I’m compelled by the critique implicit in Klein’s question: How can we hope to practice mind extension at scale without a clear understanding of which tools/techniques will give us the best bang for our buck? In other words, we need a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms in order to design more effective policies and institutions.

Paul, of course, is very interested in this question, too: One of her overt goals is to shed light on an understudied topic, and she devotes a considerable amount of effort to explaining what exactly she believes is happening in each of her examples. Among the most persuasive of these explanations is what is known as mental offloading: the use of gestures, drawing, or writing to free up space in working memory. (One example: temporarily holding a sum on your fingers to aid with mental math.)

This idea that different technologies/extensions offer different affordances to a resource-strapped brain is one that runs throughout the book. In Paul’s argument for larger/multiple monitors, for example, explains how small screens waste precious mental bandwidth on clicking, scrolling, and zooming. In contrast, she describes how, in one study:

[Bigger/better setups] induced participants to orient their own bodies toward the information they sought—rotating their torsos, turning their heads—thereby generating memory-enhancing mental tags as to the information’s spatial location. Significantly, the researchers noted, these cues were generated “without active effort.” Automatically noting place information is simply something we humans do. (149)

I found this to be a really cool explanation that rang true to experience.

In other places, however, I felt Paul/the researchers she cited were making a stronger interpretation than can actually be inferred from study results. In one experiment, for example, participants who brainstormed ideas while alternating between holding out both hands generated 50% more solutions than those who held out just one hand. In another from the same study, students who sat inside a cardboard box came up with 20% fewer solutions than those who sat outside of it (65). The researchers conclude in both these cases that subjects’ improved performance is tied to unconsciously enacting a metaphor (on the one hand…on the other hand; thinking outside the box)—which, if true, is pretty amazing! But it’s not difficult to think of alternative explanations in both experiments, either. (Something something engaging both hemispheres of the brain? Maybe claustrophobia isn’t super conducive to creativity? Although the researchers controlled for this, and the outside-the-box condition outperformed both the inside-the-box and non-box ones—so what do I know.)

My point here isn’t that I know something the researchers don’t—just that we don’t really know if the reason they provide is the real one. (It would be nice to have a few more examples out of different researchers/methods to demonstrate that this is a real phenomenon.) Though to be fair, these experiments are still a vindication of Paul’s general thesis regardless, in that movement/the environment affected cognition.

Also in this vein, I was skeptical about the direction Paul drew the causal arrow at times. She discusses two different “gesture gaps,” for example: Boys gesture more than girls, and high-income parents gesture more than low-income parents. She concludes that this helps explain boys’ superior performance on a spatial reasoning task (82), and that “differences in the way parents gesture may thus be a little-recognized driver of educational outcomes” (74). Again, this strikes me as totally plausible, but I worry that these explanations are reductive—or worse, reverse the presumed relationship.

What I was really craving, I think, were simple protocols for actually putting The Extended Mind into practice. The big picture was clear and compelling: Spend time in nature; bring other people into your creative/problem-solving process; look for opportunities to interact with knowledge on the page or in physical space. But when it came to the details of how to apply the principles, there were times I wanted more.

In “Thinking with Built Spaces,” for example, Paul makes the case against open-plan offices, explaining how they result in distraction and, counterintuitively, decrease trust and cooperation (125). Rather than constant interaction with colleagues, she argues for “intermittent collaboration”—lots of communication when clarifying the nature of a problem, then independently coming up with solutions:

Research finds that people who keep lines of communication perpetually open consistently generate middling solutions—nothing terrible, but nothing exceptional either. Meanwhile, people who isolate themselves during the solution-generation phase tend to come up with a few truly extraordinary solutions—along with a lot of losers. (128)

Plainly, great ideas come out of both individual and group problem-solving, so intermittent collaboration would seemingly offer the best of both worlds. But this feels like a fairly obvious point—and even though Paul does offer some guidance about when each kind of work should be prioritized, I can’t help but feel her prescription is incomplete: What is the golden ratio between individual and group work? How many people should be a part of a highly effective team? Don’t you need a collaboration protocol again at the end in order to winnow down the ideas that have been individually generated? (It seems to me that it often takes more collaboration to reach a consensus on a solution than it does for everyone to get an initial grasp on the problem.) So intermittent collaboration is a great start, yes, but there are still a lot of questions to be worked through for someone actually managing a team’s workflow based on the principles in The Extended Mind.

Finally, in “Thinking with Our Sensations,” Paul suggests keeping an “interoceptive journal” to measure how the outcomes of important decisions track with bodily experienced at the moment when said decisions were made:

Once you know how a particular decision turned out—Did the investment make money? Did the new hire work out? Was the out-of-town trip a good idea?—you can return to the record of the moment when you made that choice. Over time, you may perceive that these moments arrange themselves into a pattern. Perhaps you’ll see in retrospect that you experienced a constriction in your chest when you contemplated a course of action that would, in fact, have led to disappointment—but that you felt something subtly different, a lifting and opening of the ribcage, when you considered an approach that would prove successful. (32)

I’m skeptical this could work. It’s not that I don’t believe bodily awareness has value—just that this seems like a really noisy environment: one where it’s hard to imagine an individual could ever gather enough reliable data to actually draw the kinds of conclusions Paul is suggesting. (I might find it plausible with less subjective metrics, like heart rate or cortisol levels or whatever? But even that seems like it could be pretty challenging.)

Here, I think, we get to the crux of the issue with trying to explain why/how “the extended mind” works: The greater a role in cognition we grant to the environment, the more variables there are to contend with. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try to leverage mental extensions and understand how they operate, of course; but it does mean that Paul’s model of the mind—while probably more accurate—is also inherently messier and harder to study systematically. And while I don’t necessarily fault her for being unable to provide a perfect account/application of every principle she writes about, I’m not any less interested in knowing the answers.

Looping Back

Let me attempt to recap, and bring together, these various strands by way of another great anecdote from the book, about the physicist Richard Feynman:

In a post-Nobel interview with the historian Charles Weiner, Weiner referred in passing to a batch of Feynman’s original notes and sketches, observing that the materials represented “a record of the day-to-day work” done by the physicist. Instead of simply assenting to Weiner’s remark, Feynman reacted with unexpected sharpness.

“I actually did the work on paper,” he said.

“Well,” Weiner replied, “the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.”

Feynman wasn’t having it.

“No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper and this is the paper. Okay?” (158)

On the one hand, this story fits perfectly with the core claim of The Extended Mind: Feynman’s notes are clearly more than just a “record.” It’s as if Weiner had looked at a ditch Feynman dug and called a shovel the “record” of his labor. (You can understand why someone would be annoyed by the minimization!)

But again, there’s a distinction between identifying a key medium or mechanism for thinking and saying the thing is thinking itself; I can’t help but feel that distinction matters. Even Andy Clark, whom Paul quotes in her exegesis here, says: “Feynman was actually thinking on the paper. The loop through pen and paper is part of the physical machinery responsible for the shape of the flow of thoughts and ideas that we take, nonetheless, to be distinctively those of Richard Feynman” [bold text mine] (158). Just look at the verbal gymnastics Clark is doing to avoid saying writing = thinking! (Instead we get something like: thinking + paper = writing; or, thinking + writing = cognitive machinery.)

What this quote does introduce, however, is an extremely useful concept embedded in The Extended Mind: the idea of cognitive loops. Though Paul is, in a way, making a case for “loops” throughout, she does not address the topic head-on (excluding Clark’s brief reference above) until the conclusion of the book. For me this was where the whole framework finally snapped into clear focus without my getting hung up on semantics; I wish she’d started with it:

[W]hen computer scientists develop artificial intelligence systems, they don’t design machines that compute for a while, print out the results, inspect what they have produced, add some marks in the margin, circulate copies among colleagues, and then start the process again. That’s not how computers work—but it is how we work; we are “intrinsically loopy creatures,” as Clark likes to say. Something about our biological intelligence benefits from being rotated in and out of internal and external modes of cognition, from being passed among brain, body, and world. This means we should resist the urge to shunt our thinking along the linear path appropriate to a computer—input, output, done—and instead allow it to take a more winding route. (247)

What makes “the loopy mind” an improvement over “the extended mind”?

First, as I’ve been arguing throughout, I think this is just a fundamentally truer reflection of the way our brains work: “Loopy” does a better job of capturing the science Paul lays out.

Second, I think it’s a more fertile analogy and source of research questions: While “extension” emphasizes the world that is outside the brain, “loops” emphasizes both the world and the way the world is brought in; it’s more process-oriented.

Third, I think loopiness helps address some of my earlier gripes about causality: In a (feedback) loop, it’s more intuitive that the relationship between brain and environment is a two-way street (e.g., gesture ↔ inequality; NOT gesture → inequality).

Finally, if it’s not obvious, I really felt the applicability of loops in the course of writing this review, and had a lot of fun employing many of Paul’s techniques: This is a text that invites speculation and repeatedly chewing on ideas—turning them over in your mind, examining them from multiple angles, seeing where they crop up in your own life in unexpected places. In this sense, the book is a profound success.

TL;DR

The Extended Mind is an exceptionally clear, informative book whose thesis slightly overpromises in philosophical terms, but nevertheless offers a remarkable array of examples and empirical research; sometimes, the breadth of this evidence makes it difficult to know how to best apply it.

Ultimately, I recommend the book not simply for its educational value (although I learned a ton!) but for how well it captures the phenomenological experience of consciousness: As Paul argues, the human mind is not a machine sealed in a box—it is a dynamic process of assembly, constantly and iteratively constructing reality in every waking moment.