It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than think your way into a new way of acting. -Jerry Sternin

In the short history of this blog, I’ve shared several dozen favorite quotes—but if forced to choose just one, it might be the simple idea expressed above, from former Save the Children and Peace Corps director Jerry Sternin. (There are other variations on the same sentiment floating around the internet, too.)

This claim, “beliefs follow behavior” runs counter to our intuitive experience of the world. That is, actions are usually seen as a natural consequence of our wants and needs—and, to be sure, they very often are. But much more often than you’d imagine, the causal arrow goes in the other direction: You do something, and then your attitude changes accordingly. Below are but a few examples of this phenomenon across different domains:

Persuasion via role play — Research has repeatedly shown (see, e.g., here and here) that people randomly assigned to argue a position end up significantly more likely to actually endorse that position. Robert Cialdini, the preeminent researcher of persuasion, describes a friend who got significantly more job offers after asking interviewers to describe what drew them to his resume. In both these cases, the intervention is obvious (participants could just have easily been assigned to the other position; the interviewer could have been asked to voice concerns or reservations), yet their targets end up genuinely convinced of the arguments—this despite knowing full well they were prompted to make the case. Beliefs follow behavior.

Justification of sunk costs — When we go through a difficult initiation process or undertake significant costs (in time or money) to achieve a goal, we are faced with the reality of having to account for our choices. It’s possible, of course, to realize that we invested effort to reach a reward that was not worth it; but this would imply poor judgment and create cognitive dissonance. More often, we minimize regret by concluding that the costs we bore really were worth it, regardless of what we have to show for our efforts. (“I may not have won the competition, but I made so many great friends along the way!” “The relationship may have ended with him slashing the tires of my car, but I learned so much about what I’m looking for in a partner!”) In hindsight, you can almost always find a good reason for having done something—even if it’s not the one you would have cited at the outset. Beliefs follow behavior.

Acquired tastes and habits — People struggling to start exercising are often advised to just put on their workout clothes and walk to the gym—even if they immediately turn around and head home. Young children are often advised to just try unappetizing vegetables—even if they immediately spit out the offending greens. Given enough exposure, it seems, most people who go to the gym every day eventually start thinking of themselves as gym-goers, and most people who eat tons of spinach eventually start not minding the taste. Beliefs follow behavior.

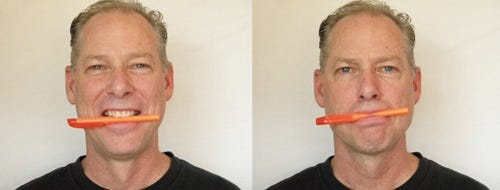

Reverse engineering emotions — You know the feeling: You’re feeling sluggish or depressed, but you force yourself to get out of the house and see friends; suddenly you really do start feeling better! There are even famous—albeit contested—examples of reverse-engineered emotions in the lab: decreased confidence results from taking up less physical space; positive mood results from being induced to smile. Although the original size and generalizability of both power posing and the pencil study were overstated, it seems like there’s some effect there. Translation: If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands—but if you’re not happy, clap anyway; there’s a decent chance it will cheer your sad ass up! Beliefs follow behavior.

Spirituality via ritual — In my early twenties, I (regrettably) went through a somewhat vocal and obnoxious atheist phase. Having emerged on the other side, I’ve come to once more appreciate many of the rituals I grew up with—like lighting candles and singing religious melodies. But it was only after, e.g., consistently building a Shabbat-like practice back into my life that Saturdays started to take on a sense of restfulness. This is, I think, a common experience: In many faith traditions (and secular ones as well) a sense of sanctity is achieved only after certain practices have been instilled over many years through sheer repetition, often starting at an early age. Beliefs follow behavior.

Empathy via expanded rights — Frequently, when we tell the story of women’s suffrage, school integration, or gay marriage, we point to attitude shifts spurred by a small and resilient group of political activists. This credit is surely warranted—but it also misses just how much progress is often made after rights are enshrined in law. If we look, for example, at American support for gay marriage between 1996 (just twenty-seven percent) and today (over seventy percent), we can see that the majority of this progress occurred in the wake of 2004, when Massachusetts became the first state to recognize same-sex marriage; support has continued to trend steadily upwards after the Supreme Court’s landmark decisions in 2013 and 2015. This suggests a virtuous cycle such that, if you’re forced to treat people more equally, you just might start seeing them as equals. Beliefs follow behavior.

Inspiration via action — Naive attitudes toward creativity hold that creators simply have a brilliant vision and execute it. The reality described by professional artists, inventors, and entrepreneurs is usually more complicated: an iterative process of producing something and reacting to the content they’ve just put on the page or canvas. (The architect Gabriela Goldschmidt calls this “the backtalk of self-generated sketches.”) Put another way: You think the writers of Succession had this S2.E9 scene in mind when they named their characters Greg and Tom at the start of the show? You think Mark Zuckerberg was envisioning the Metaverse back when he created Facemash? The truth is, creators often have some initial ideas, but they don’t really figure out what their project is about or why it matters until after they start making it. Beliefs follow behavior.

This list is by no means exhaustive—but I hope the examples above are enough to drive my point home. Again, I’m not arguing that life never works the intuitive way (i.e., behaviors follow beliefs); but no one really has to be convinced of that because it’s consistent with our subjective experience. What remains frustratingly unintuitive, no matter how many times you see it working, is that in many places you’d least expect, “fake it till you make it” is a surprisingly viable strategy.

If you remain skeptical that beliefs follow behavior, I can offer only this humble suggestion: Try it for yourself. Try it a few times to really get a sense of it. Try it enough, with sincere and consistent effort, and I think you just might come around…

Ready, shoot, aim!